THE OPENING is all about introducing the fascinating, quirky and wonderful people working in and around the visual arts in Vancouver.

|

|

THE OPENING is all about introducing the fascinating, quirky and wonderful people working in and around the visual arts in Vancouver. Each week, we’ll feature an artist, collective, curator or administrator to delve deep into who and what makes art happen! |

Heavily interested in the history of art and those who have changed art before him, Damian Moppett creates detailed homages to these moments of change. The interdisciplinary artist's work is currently being exhibited at Rennie Collection in Chinatown, the collected works spanning over 8 years of Moppett's practice.

'Untitled' 1998, acrylic on canvas (courtesy Rennie Collection. Photo: artist)

I know you grew up surrounded by art. Can you tell me a bit about your family's artistic history?

Both my Mom and Dad are professional artists, and my Dad is a traditional abstract painter. When I grew up in Calgary, he was the curator of what's now called the Illingworth-Kerr Gallery at the Alberta College of Art [now Alberta College of Art and Design]. He had a studio downtown. My Mom had a studio in various places over the years - downtown, our garage. She was teaching at the Alberta College of Art mostly in drawing, sometimes in sculpture. So yeah, I was surrounded by art. My Dad's brother was a curator at the Mendel in Saskatoon. My paternal grandmother was a painter, my maternal grandfather was a painter and a potter, and started Ceramic Arts in Calgary, which had a number of West Coast potters there. He started the ceramic department at ACA as well. Yeah, art wasn't an alien thing. I didn't always think I was going to be an artist but I drew all the time. My Dad taught me how to paint, and we would argue about art when I was a kid. But I wanted to be a race-car driver for a long time. My hero was Gilles Villeneuve.

When you finished high school, did you start out going to school for art?

I took night painting classes with Iain Baxter when I was in high school, and liked that. Then I got into ACA when I was 17 and did two years there. I realized that... my Dad was at the gallery, my Mom was teaching, and fellow students would say things about them to me without realizing. It was just really difficult having my parents in the school, so I had to leave. I applied to transfer to the Ontario College of Art [now Ontario College of Art and Design] in Toronto and moved there when I was 18. I didn't like it. I went to OCA for two weeks and dropped out. I was supposed to be going into third year but they didn't have enough studio space, teachers didn't show up for class, and I didn't know anyone my age in Toronto. So I left and decided to come to Vancouver. I took a year off and painted on the fire escape of my apartment in the West End, and then applied to Emily Carr and got in. It worked out well because Steven Shearer, Ron Terada, Allan Switzer and Peter Jensen were there - good people to fall in with.

Obviously your family had an influence on what you became. Do they still have an influence on you now?

Yes. When I was first in art school I was actively making art that was opposed to their method of art-making. As time goes on you mellow though. My last show at Catriona Jeffries was the first show that the influence of them, in particular my Dad's painting style, had been apparent in my work. It was something I fought against at first but embrace now.

What other things typically influence you?

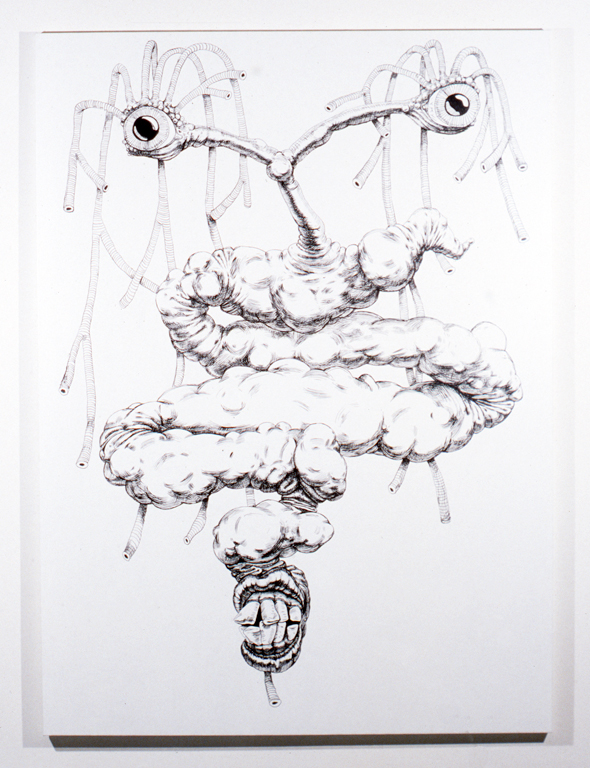

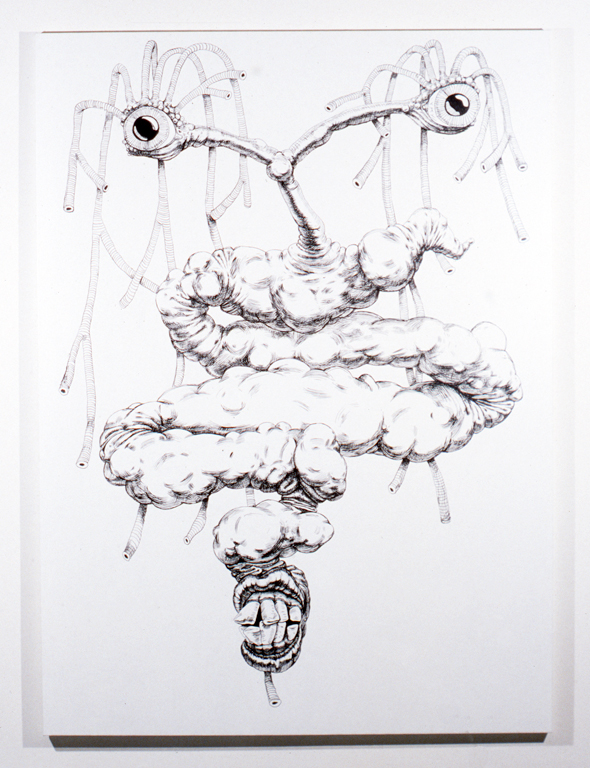

There are obvious references in the work that's in the Rennie Collection exhibit - Mike Kelley, Anthony Caro, Alexander Calder. I used to be a big fan of Martin Kippenberger's work... I've always been interested in painters, even though most of my work seems to be about sculptors. I enjoy looking at and thinking about painting the most.

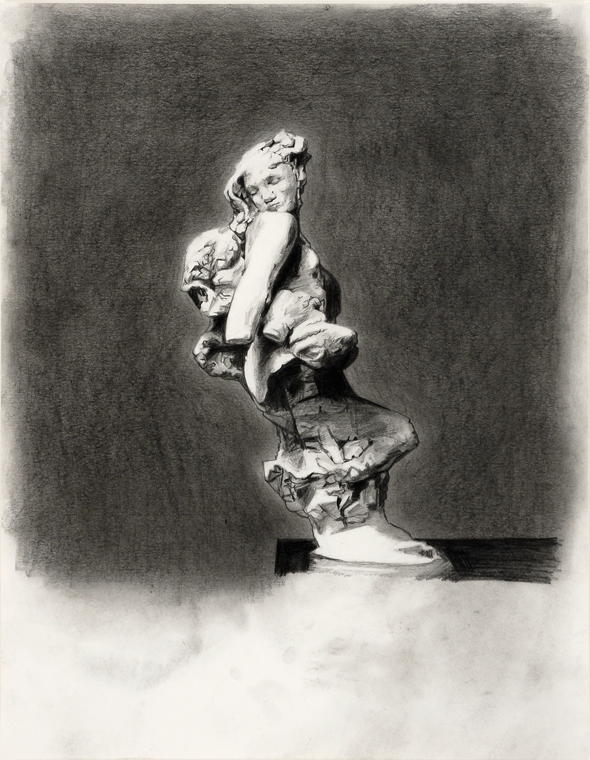

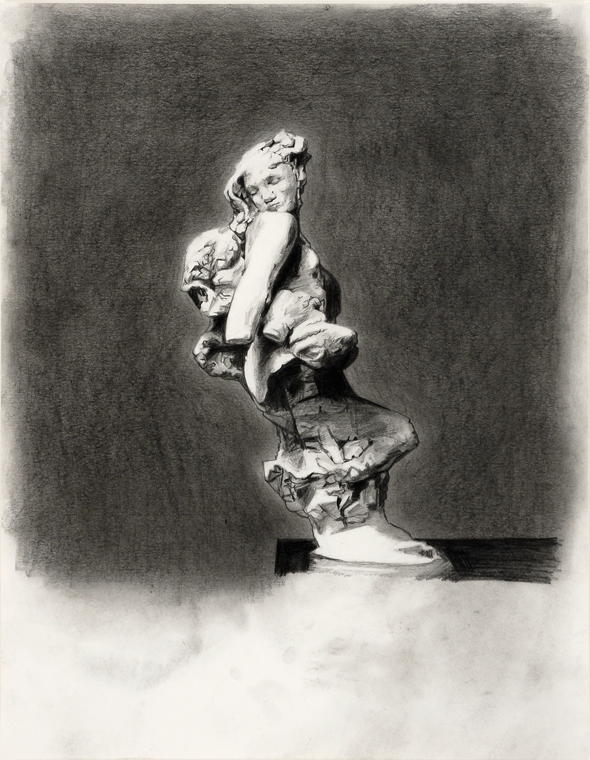

'Rodin's Triton + Nereid' 2006, graphite on paper (courtesy Rennie Collection. Photo: artist)

Would you consider yourself an appropriator, or are you just continuing an ongoing conversation in art?

Everybody’s version of appropriation is different, but to me that word seems to denote an aesthetic appropriation. I wouldn't want to claim that my level of investigation is any deeper than anyone else's but I don't like to use the word appropriation. It's hard to find a word that works actually; inhabiting is an impossibility and pretentious. Something like investigation I think makes the most sense in terms of looking at not just a specific work by an artist, and not just one artist either but more a period or a time. I’m investigating periods of transition in terms of a moment in art history.

'Medaro Rosso's 'Bambino Malato' in Wax Over Plaster' 2005, watercolour on paper (courtesy Rennie Collection. Photo: artist)

So you like to investigate those bigger moments in art?

Yeah. And then try to signal those in my work by using specific works that are sort of keys to understanding a moment. For example, a move from figuration into abstraction using Rodin as a key example for that, and making a sculpture or two, then referencing the work of Medaro Rosso and Brancusi in the drawings to fill that out. Those three guys are key in my mind in terms of moving from figurative representation to abstraction, and also in terms of dealing with photography and painting and it's relationship to sculpture. Medaro Rosso would photograph his sculptures and then take the negatives and cut and paint on the negatives and make a print of that. So it's kind of a weird triangulation of painting, photography and sculpture. Brancusi would photograph his sculptures in the studio, and that was sort of the ideal situation for viewing his sculptures in his mind. The photographs act as a perfect representation of this sculptural form, which is not how we normally understand our relationship to sculpture. To have it mediated by a photographic apparatus is unusual. When you look at something like that historically, it's amazingly innovative. But it's not a widely known thing. It's not my discovery, but it's something that I'm interested in, and it relates to how I've dealt with sculpture in my work.

Is it really important in this particular exhibition at Rennie that you can see both the process and then the final work?

Absolutely. Particularly in the watercolours and drawings the studio images are most of them documenting works in progress. That's the biggest formation in the gallery. That shows works in transition, some works that have been destroyed... I'm interested in showing the process very much. I find sometimes the final object, especially in terms of sculpture to be quite frustrating and never quite enough.

'Broken Fall' 2011, aluminum and steel (courtesy Rennie Collection. Photo: SITE Photography)

Were you creating the drawings and watercolours before it became a project with Bob Rennie?

I had started it and shown the first 40 at the Contemporary Art Gallery show 'Visible Work.' He was interested in acquiring it but it wasn't finished; it was an open-ended project that I was just going to add to continually until some mysterious point where it was done, which is now. He committed to acquiring everything and keeping it together, which was a godsend for me because I didn't want to make a work of 128 drawings and watercolours and have them go to a collector here and a collector there - getting them back for a show in the future would be a logistical nightmare.

Can you tell me a bit about the artist-collector relationship, particularly with Bob and his partner Carey?

My relationship with them is much more involved than any other relationship I've had with a collector. There has always been a conversation in terms of what would make sense in the Collection and representing my work. Other collectors don't have anywhere near the commitment to my practice that Bob and Carey have, and they don't take that responsibility lightly. They're interested in having a dialogue with the artist, and it's not just about what they like aesthetically or having criteria for collection. Just like other artists they collect in depth, they are trying to represent the artist’s oeuvre in a responsible manner.

'Studio at Dawn' 2009, steel, enamel, earthenware and stoneware (courtesy Rennie Collection. Photo: SITE Photography)

What was your thought process in creating Broken Fall for the giant room at Rennie?

It came from looking at that space and finding it to be a really difficult exhibition space in terms of how tall it is. Most of my work is not that big so I was really worried that it would swallow up anything that was put in it. Richard Jackson has much bigger, louder installation works so I can imagine it was not much of a worry for him, but I was really worried! I wanted put up a work that used that space. Also I'd always seen

Studio at Dawn going in that space, so I wanted to make a companion for it in a way. That's kind of how I work sculpturally - I make a sculpture, figure out what it's not doing properly, and then the next step would be to make a companion piece, like

Fallen Caryatid and

The Acrobat.

Studio at Dawn needed a buddy and I wanted to make a mobile. It was also a perfect opportunity for me to make a more ambitious sculpture but far simpler sculpture. All of my works have an obvious historical reference and then have my alteration or my hand obvious as well. Usually my involvement in that moment or work is more elaborate than the reference point. In the case of

Broken Fall, I wanted my hand to be really simple. Outside of the fact that I designed the mobile, I wanted it to be representative of a generic mobile, and my involvement was just to break it and make it imbalanced. I was really excited about the opportunity to make that really simple gesture. It seemed to me the perfect next step when you think about postmodernism and dealing with history and that responsibility.

Tell me about the conversation going on between Studio at Dawn and Broken Fall.

It's a simple one. It's just taking the colour from the original Anthony Caro

Early One Morning piece and then transferring it on to the mobile. It's not a complicated relationship at all; it's completely formal.

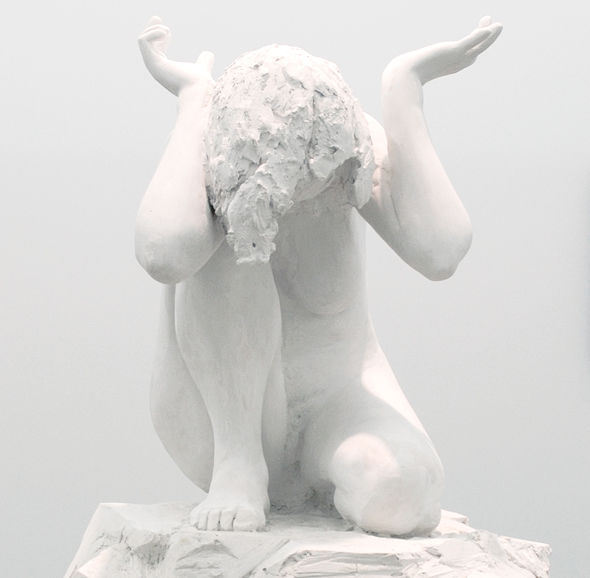

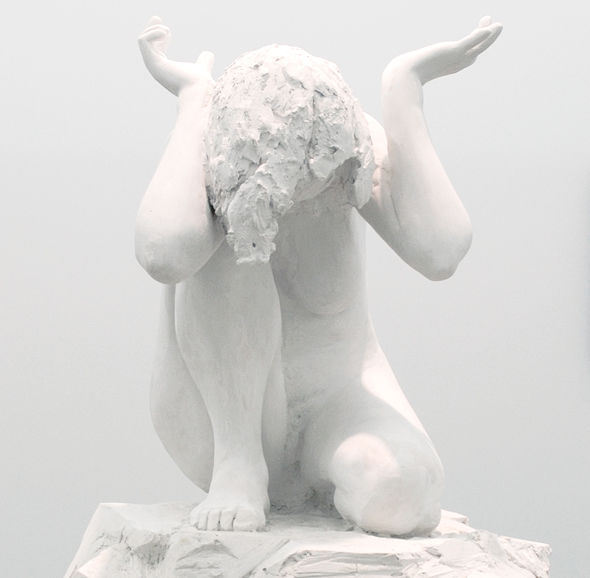

'Fallen Caryatid' 2006, plaster (courtesy Rennie Collection. Photo: SITE Photography)

Can you speak a bit more to the relationship between Fallen Caryatid and The Acrobat as well?

Every time I've shown

Fallen Caryatid I've shown

The Acrobat, except for the Carleton University Art Gallery show. I was uncomfortable with having a figurative representation of a naked woman stand-alone without some sort of yin to its yang. Also the problems with representing the other made me want to throw myself or a male figure in there to balance it. In terms of how it's exhibited at Rennie Collection... a lot of the decisions about how the show is laid out are aesthetic, and everything transitions from one room to another. That room ended up being this quasi-museum room because its Rubens copies and traditional figurative plaster sculptures. It made sense in terms of having the distant historical references combined in this cozy room.

------------

Damian Moppett lives and works in Vancouver. He received a BFA from Emily Carr College of Art and Design in 1992 and a MFA from Concordia University in Montreal in 1995. His work has been exhibited the Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver; Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver; Carleton University Art Gallery, Ottawa; National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa;Yvon Lambert, New York; Witte de With, Rotterdam; and Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh. He is represented by

Catriona Jeffries Gallery in Vancouver.

Damian Moppett: Collected Works is on at Rennie Collection until April 21, 2012. The exhibition is open to the public by guided tour most Thursdays and Saturdays; to make an appointment please visit the

Rennie Collection website.