A Vancouver time travelogue brought to you by Past Tense.

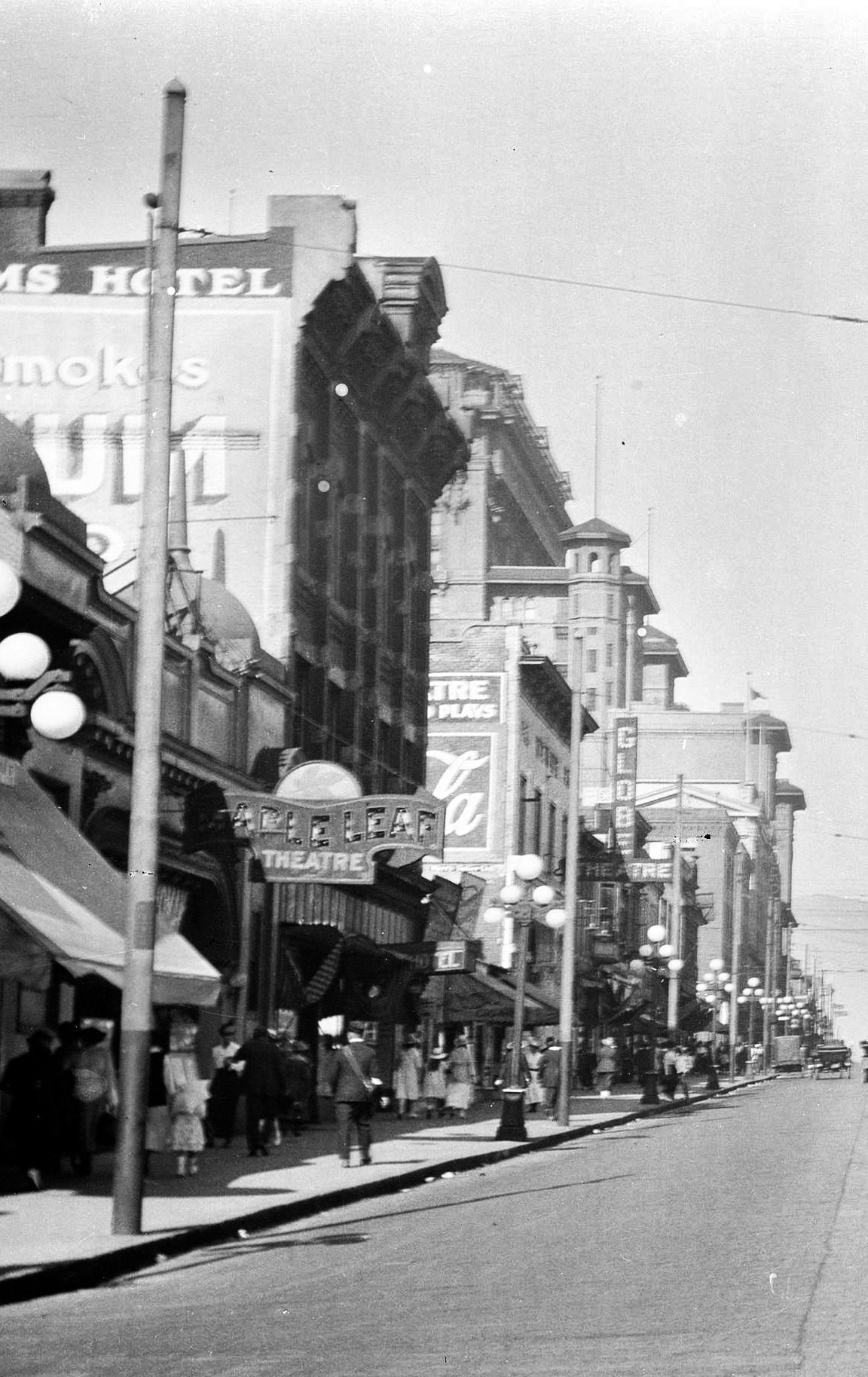

Granville Street, showing the Maple Leaf Theatre on the left.

Granville Street, showing the Maple Leaf Theatre on the left.

The arrival of sound films, or “talkies,” is usually associated with the 1927 film, The Jazz Singer. This classic launched the rise of talking pictures and triggered the rapid decline of silent films, but it also represents the culmination of many years of experimentation in a race to develop a commercially viable system of synchronizing recorded sound with motion pictures.

The race to bring talking pictures to the public resulted in Vancouver having not just one, but two theatres specializing in talking pictures between 1908 and 1909. The first was the Maple Leaf Theatre on the 800 block of Granville (on the left in the photo), which installed the Chronophone system developed by Leon Gaumont in France in 1903. Chronophone included two gramophones amplified by compressed air. A deft operator was expected to seamlessly switch records while maintaining synchronization with the action on the screen.

It wasn’t a perfect system, but you’d never know from the publicity:

The pictures of the actors on the screen not only move in pantomine, but their lips move and there appears to issue from them the words just as from the lips of a living person; thus the Chronophone accomplishes by a perfect system of electrical synchromism between the projecting and talking machines.

The Maple Leaf was one of several theatres in various cities to install the chronophone, but it was the first in Canada. The films themselves were shorts, including scenes from the French coast, singing by a popular Australian singer, and songs like “Waltz Me Around Again, Willie” and “Regiment of Frocks and Frills.” Attendance in the opening week was apparently smaller than hoped, so the Maple Leaf “substantially” reduced the price of admission to ten cents.

The chronophone’s biggest competitor was the New York-based Cameraphone, which added Vancouver as one of the urban markets testing it’s own talking picture system on 28 November 1908, three months after the chronophone’s debut at the Maple Leaf. On the same day, the Maple Leaf re-opened after being closed for renovations. It was now “the prettiest place of amusement on the Pacific Coast,” but the chronophone machine hadn’t yet been reinstalled after being sent off for upgrades. When it returned, the theatre promised that an expert would be on hand so that “the pictures would really and actually ‘talk.’” This was the first indication that the technology was less than perfect.

There were several issues still to be worked out in talking picture technology. Consistent synchronization was perhaps the main problem. Another was that the sound quality from gramophones wasn’t yet up to the task; while gramophones were adequate for home enjoyment, the amplification needed to fill a theatre made them sound metallic and shrill. Many people seem to have been impressed by the novelty of talking pictures, but the many technical problems meant it would be years before they were a commercially viable form of mass entertainment. Chronophone films at the Maple Leaf seem to have ended by March 1909 and on 5 July the Cameraphone Theatre at 58 West Hastings was rebranded The National, a regular vaudeville theatre featuring live acts and silent films.

Source: Photo of Granville Street (1920, cropped), City of Vancouver Archives #1376-129