The decisive referendum victory to preserve the first-past-the-post electoral system in British Columbia is, quite naturally, a repudiation of those who sought proportional representation (PR). That goes with the territory of a fight.

How much of the rejection John Horgan will wear, we will not know for some time. But this was his first effort to lead a campaign and the electorate did not follow. And really, he must have been shocked by the margin of defeat, a full 23 points. No jaw could have been ready to so drop.

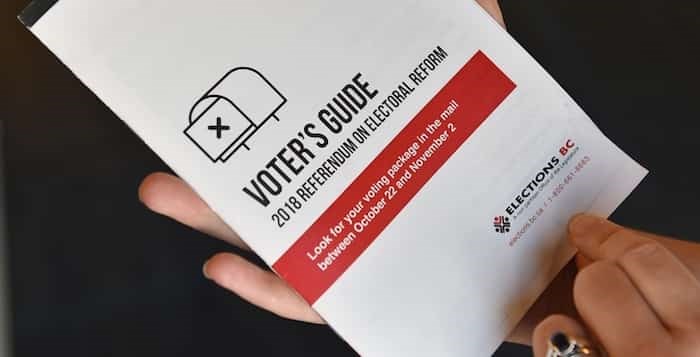

Ballots start going out to households this week asking whether B.C. should switch from the current first-past-the-post election system to a system of proportional representation. The second question asks voters to rank three systems of proportional representation. Photo Dan Toulgoet

Ballots start going out to households this week asking whether B.C. should switch from the current first-past-the-post election system to a system of proportional representation. The second question asks voters to rank three systems of proportional representation. Photo Dan Toulgoet

PR always had a PR problem: a rushed and roughshod process, a sly political expediency to acquire power and confusion about the three options – two of them untested anywhere. It was like a bad version of Brexit, far too murky and partisan to be credible as a consensual exercise.

In the end, 61.3% of the more than 1.4 million ballots cast said no way. I suspect that number could have been even larger, because some were so baffled by the options that they chose not to participate out of ill-informed worry.

It now clears the last hurdle for Horgan to call a spring election. He has fulfilled the largest commitment of his Confidence and Supply Agreement to share power with the BC Green Party. He can cut them loose and try to win a majority, ironically in the electoral system he campaigned against.

Then again, his support for PR never felt like it came from a belly of fire. He spoke the scripted words but sported a thought bubble that his mission, should it be successful, would deny the NDP a majority forevermore. Now he gets it both ways: he did what he had to do in the short term to most optimally pave the long term. We shall see about that, though.

It isn’t as if the Green leader, Andrew Weaver, was a big loser in the campaign he most savoured. Nearly two in five voted, in broad outline, for a system of proportional representation. But that was the problem: nothing specific was offered.

The message of his campaign was blurred – some might even think sabotaged – by the determination that three choices would be on the ballot and that a legislative committee would then ruminate on the implementation. The three proposals created option paralysis; no choice among the three earned a majority of the PR supporters. And trusting a political committee to reach some sort of altruistic objective on an important matter like electoral reform is naive beyond compare.

In the end, only 15 of the province’s 87 ridings, including six in Vancouver and a batch on Vancouver Island, voted in favour of PR. (Please, Islanders, don’t start a secession campaign.) Even Weaver’s Oak Bay-Gordon Head riding – which one would presume to be ground zero for the PR movement – barely endorsed it.

The takeaway from this campaign is that the process matters. Even PR proponents were admitting that the process was more hindrance than help. It needed to start with a clear choice, a truer incentive for voter turnout, a protracted campaign less driven by self-interested political leadership, and a threshold of change that would have ensured each region of the province was, well, proportionally represented in the result. We got none of that on offer, so the flawed process provided an additional argument to those trying to preserve first-past-the-post.

The loss was self-inflicted and the damage to the PR movement is self-evident. Three referenda now over 13 years have shown no particular growth for the movement. The true believers have lost and lost and lost and the people have spoken and spoken and spoken. Give it a rest.

That being said, there is little disagreement even among those opposed to PR that much can be done to fix elements of the system to effect more trust in it: online voting, requirements for voting, more ridings, freer votes in the legislature, partial elections, term limits, more transparency in government operations, on and on the list could go.

The referendum result still indicates disquiet worth addressing, but inside a system and not overriding a system. On that we can all look forward.