MONTREAL — The notion that Canadian companies can simply switch supply chains in response to American tariffs is a fantasy, experts say.

With 25 per cent duties levied on some Canadian goods and the possibility of more tariffs to come, businesses north of the border are looking elsewhere to source their material and sell their products.

But companies caught up in tightly braided supply channels after decades of trade pacts and sector specialization may quickly bump into barriers around everything from transport and labour costs to resource availability, manufacturing capacity and market saturation.

"There are many, many industries that can't just flip a switch," said Ulrich Paschen, an instructor at Kwantlen Polytechnic University’s Melville School of Business.

The auto sector illustrates the difficulty many firms face. Canada exports about 1.5 million fully assembled vehicles to the U.S. each year and accounts for eight to 10 per cent of American vehicle consumption — and nearly all of Canada's auto exports — according to the Canadian Chamber of Commerce.

Nor are American automakers necessarily inclined to turn their back on their northern partners. Cancelling contracts with Canadian suppliers would trigger breakage fees of up to $500 million per U.S. factory, the group said. Many parts cross the border multiple times before final assembly.

"Canada and the U.S. have that integrated trading relationship. It's been built over decades," said Pascal Chan, vice-president of strategic policy and supply chains at the chamber.

"It's not easy to unwind and just unscramble the egg that is this trading relationship."

Canadian auto suppliers considering relocation to the U.S. would confront major deterrents as well — closure costs in the tens of millions per facility, labour expenses that are over 20 per cent higher and multi-year delays to get their American plants up and running.

Auto, lumber and steel producers would face some of the toughest challenges in the hunt for new markets, Paschen said.

"There is a finite number of companies that can make those components, and they would not be easily replaced," he said of vehicle parts.

Forestry players face an entirely different dilemma. Lumber exports, while ample, have a low value per volume compared to some other commodities.

"It makes a lot of sense to ship stuff from Canada across the border directly to the United States. It makes a lot less sense to ship it halfway across the world, because the transport cost becomes such a huge factor," Paschen said.

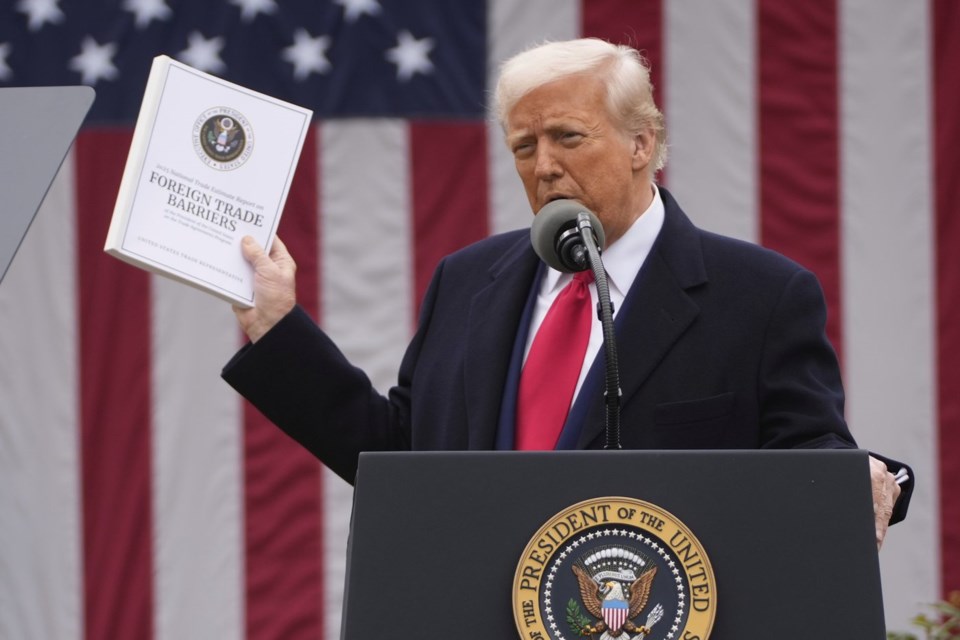

As for steel and aluminum, U.S. President Donald Trump imposed 25 per cent tariffs on imports from all countries in March, on the heels of duties on a range of other Canadian-made goods. Canada struck back in both cases, announcing tariffs of about $60 billion worth of goods in total last month.

Canada is by far the largest source of aluminum for the U.S., shipping US$11.4-billion worth of products ranging from wire to piping there in 2024 — the next biggest supplier, China, shipped US$2.9 billion — according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Canada is also America's biggest source of foreign steel and iron at US$13 billion, though China and Mexico are not far behind.

The sheer volume of the commodities would make it hard to ship to other markets, experts say.

Meanwhile, a push to domesticate production beyond a basic level to churn out finished goods — a struggle for Canadian companies since Confederation — would take time, investment and possibly government support.

"While the steel may be produced in Canada, it has to go to the U.S. to be turned into a structural element that is then used in the construction of a building in Canada," said Jesus Ballesteros, manufacturing industry leader for consulting firm BDO Canada.

"Raw aluminum gets sent down to the U.S. It's processed into sheets or potentially even the finished cans, and then those cans then get shipped back to Canada to be used for beer or other drinks," he continued.

"That's where we get caught in the tariffs ... Now, can Canadian industry move in that direction?"

Limited supply chain flexibility extends far beyond the production lines and blast furnaces of heavy industry. Canada's vast geography and small population relative to the U.S. amount to hurdles for enterprises looking to bolster their domestic market, while most countries beyond the U.S. seem out of reach to many players.

"If we are not delivering to the States, we are sort of an island. Things need to go on long voyages from Canada to reach customers that are not in North America," said Paschen.

Companies will be loathe to make major changes to their supply chains unless they think hefty tariffs are here for the long haul, he said.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published April 3, 2025.

Christopher Reynolds, The Canadian Press