The provincial government’s use of time extensions for British Columbia’s information access requests is undermining the province’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA), says the province’s information and privacy commissioner.

“This must end,” Michael McEvoy said in a report released Sept. 2.

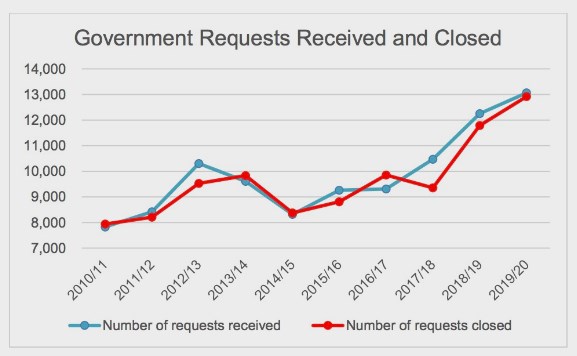

The good news on B.C. government openness is that the general response time to requests for information has decreased, McEvoy said.

The bad news, he said in a report released Sept. 2, is that “between April 1, 2017, and March 31, 2020, government took it upon themselves, in over 4,000 cases, to extend the response time for an access request without any legal right to do so.”

He called it an untenable situation that has become part of government culture in how Victoria handles requests under FIPPA.

“My worry is that, over time, a culture of acceptance has grown around this issue, affecting government’s attitude toward the problem, and also, to be frank, the approach my office has taken,” McEvoy said in the report. “This must end.”

“I am deeply troubled by the large number of cases left unanswered within the time limits set out in FIPPA,” McEvoy said. “This state of affairs cannot continue without bringing British Columbia’s access to information law into disrepute.”

McEvoy said in an interview that extensions past 60 days must be justified to and approved by his office.

“They simply ignore the rules,” McEvoy said. “This is a systemic issue because the public begins to lose faith in the system when the government refuses to play by the rules.”

He said FIPPA reform is needed.

“It would be my hope that government will bring political will to fixing what needs to be fixed in the system,” he said. “There needs to be a culture shift here.”

The report said in the three years covered in the report, government responded to about two-thirds of requests within the standard 30 business-day timeline set out in FIPPA. The legislation also allows public bodies to extend the 30-day time limit for responding to requests by another 30 days in defined circumstances.

McEvoy said Victoria is relying more and more on extensions – albeit as the number of requests rises. Further, he said, there are an increasing number of responses indicating no records.

But, McEvoy said, the latest reporting period shows acceleration in the number of files that exceed legislated timelines.

“This represents a blight on the access system that damages the integrity of B.C.'s access to information law,” he said. “The timeline provisions in FIPPA are not suggestions; they are legal obligations.”

The report is based on information provided by Information Access Operations, which operates under the Ministry of Citizens' Services and processes access requests received by all government ministries and select public bodies, including the Office of the Premier.

Analysts in McEvoy’s office looked at the percentage of requests responded to in compliance with FIPPA timelines, average business days spent processing requests and the average business days a response is delayed beyond FIPPA timelines.

The report makes four recommendations to fix the system: monitoring extensions with a view to reducing their usage, proactively disclosing records, expanding presumptive sign-off policies and exploring automation for the processing of records.

McEvoy also said the use of public bodies hiding disclosure through subsidiary organizations doing work in the public interest must stop.

“That is simply wrong,” he said.

Sean Holman, a journalism professor at Calgary’s Mount Royal University and former Victoria investigative reporter, said the disclosure of information has become a partisan issue when it should be a democratic issue.

He said the B.C. Liberal Opposition now uses the access to information system to find information on government, just as the NDP did when it was in opposition.

Holman said it’s a shame the NDP is not using its power to reform the system it once relied on to hold the Liberals to account. And, he added, “it’s ironic [the Liberals] are now using the system that they themselves failed to reform.”

But, he said, the issue is fundamentally one of government transparency where government should have fewer exemptions to use and less power to censor.

“We can’t have a system where the release of information that has been paid for by the public and, which in many cases, the public has a right to, is put behind a paywall.”

McEvoy said those exemptions have steadily grown over time.

“We don’t think that is in the public interest.”

That must also be dealt with in legislative reform, McEvoy said.

McEvoy said in June Victoria needs to do more to disclose operational information to the public. He said the issue is one of transparency for voters in a healthy democracy, and he detailed suggested changes in a report.

The commissioner said while some public bodies meet their obligations under provincial law in disclosing information without official request, others can do more to meet those legal obligations.

“How can you judge a government, if you don’t know what they are doing?” McEvoy asked at the time.

A Glacier Media analysis of federal agencies showed that while the COVID-19 pandemic has slowed Ottawa’s handling of access to information requests, the country’s law enforcement agencies and defence department are often unable to meet legislated response requirements.

But, a July 22 report to Parliament from federal Information Commissioner of Canada Caroline Maynard examined Department of National Defence handling of requests. In her recommendations, she said other government institutions should take note that Canadians have a “quasi-constitutional right to access government information is not compromised,” she said.

@jhainswo