Aaron Volpatti was on fire.

That’s not a colourful expression to describe a scoring streak or a great game on the ice, where Volpatti played for the Vernon Vipers of the BCHL. No, Volpatti was literally on fire.

A moment earlier, Volpatti had felt invincible, like many teenagers do. He was on a camping trip with his Vipers teammates, partying away the frustration of losing the 2005 BCHL championship to the Surrey Eagles while also sending off the veteran players who were graduating out of junior hockey.

Volpatti revelled in being that “crazy guy” who would do anything to make his teammates laugh and keep them entertained. He had what he called a “pyro show” with gasoline and fire that went off without a hitch the year before, but this time his wine bottles of gasoline had broken, soaking his clothes in fuel.

It didn’t help that Volpatti had been drinking and wasn’t thinking clearly. While he didn’t have anywhere near enough respect for the dangers of gasoline and gasoline vapours, he knew enough to not get too close to the fire. Still, he decided he wanted to get rid of his gasoline-soaked sweater, and what better way to do it than to throw it in the fire, creating the pyrotechnic spectacle that he desired?

“I was really just a walking bomb,” recalls Volpatti. “I went to throw my sweater in the fire and it was like a detonator cord for dynamite.”

Volpatti exploded.

The foolish mistake nearly cost him everything he had worked toward in his life; it led to a turning point in his life that changed everything.

"College hockey was my NHL."

Hockey was everything for Volpatti as he grew up in Revelstoke, B.C. He had dreams when he was a kid of playing in the NHL, as most kids with skates and a stick do, but he became a realist as he became a teenager.

“I was just a pretty average hockey player,” says Volpatti. “I was above average for Revelstoke but I got cut from select teams and played house hockey at 14 years old — not the track that most people are on to go to the NHL.”

So, his dreams grew smaller. If the NHL wasn’t a possibility, he could at least work his way onto a Junior A team in the BCHL and possibly earn a scholarship to play university hockey and pay for his education.

“College hockey was my NHL,” he says. “Pro hockey wasn’t even on my radar — if I could get my education through hockey, that was my dream. That’s what I chased from probably the age of 13 or 14.”

Volpatti knew he wasn’t going to accomplish that dream with elite skill and highlight-reel goals. After a stint in Junior B hockey with the Revelstoke Grizzlies, he hit and scrapped his way into a fourth-line role with the Vipers. He recalls how every step he took to the next level of hockey, he reset to what he knew best: hitting, skating, and fighting. That’s what got him into the lineup and that’s what kept him there.

He reasoned that he could work his way up the lineup in the years to come, adding penalty killing and more icetime until maybe by his final year in junior at the age of 20, he could score enough to get the attention of a college scout or two. He barely even dreamed of playing Division I NCAA hockey in the U.S., thinking he might be able to land on the roster of a Division III school.

"I was 100% burned."

Volpatti was on his way toward that modest dream. In the 2004-05 season, his second year of Junior A, Volpatti chipped in a little more offence with 18 points in 57 games and played a larger role as a crash-and-bang forechecking winger. As he was sending off the Vipers veterans on that fateful camping trip, he knew he would be one of those veterans next season and be relied upon to do more scoring.

Then the fire drove everything else from his mind. He sprinted in a blind panic as the flames jumped up his sweater, then burst up his gasoline-covered clothes to cover his entire body.

“The fight-or-flight took over and I just bolted and ran. That was probably the worst thing I could have done because I was pretty fast and no one could catch me,” says Volpatti, with a wry tone. He was always known for his speed.

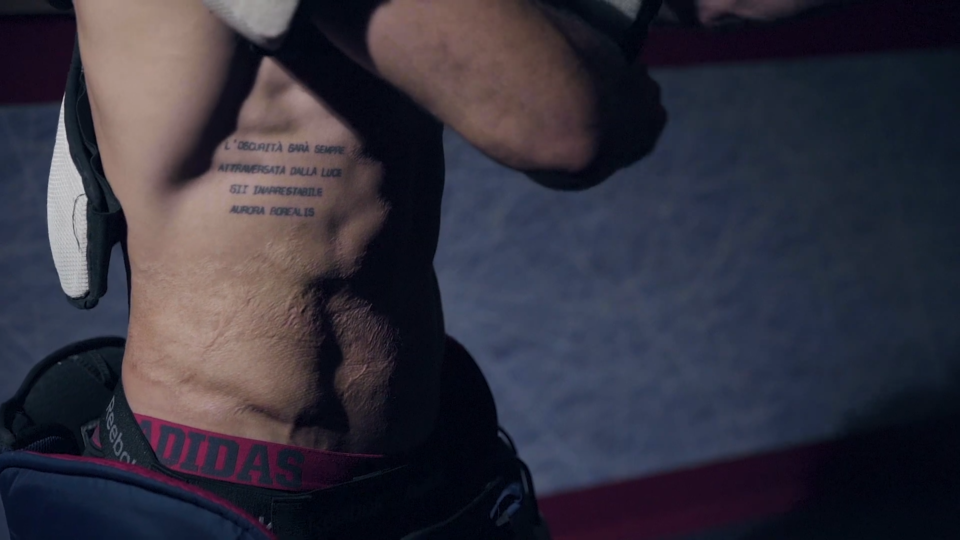

Volpatti had to be airlifted to Vancouver that night to the burn unit, where he would spend the next several months. He had second and third-degree burns over 40% of his body and first-degree burns on the rest.

“I was in pretty bad shape and pretty foggy,” he recalls. “You’re on a lot of painkillers, a lot of morphine. I remember opening my eyes the next day at some point and seeing my parents there and pretty emotional and I'm wrapped up like a mummy. I was 100% burned.”

Volpatti had to undergo debridement, which is the complete removal of dead, damaged, and infected tissue from a wound.

“I like to call it torture — they basically skin you alive,” says Volpatti. “It’s pretty gruesome.”

It wasn’t until after the first debridement procedure that Volpatti was alert enough to have a conversation with his doctor. He informed Volpatti that he would be spending the entire summer in the Vancouver General Hospital burn unit but reassured him that he would make a full recovery.

"My career was over in that moment."

For the first time, Volpatti’s thoughts turned back to hockey — would he be able to play again? Would he be able to return for training camp to play his final year of Junior A with the Vipers and fulfill his dream of earning a scholarship?

“It was a look that I’ll never forget,” says Volpatti. “He just froze, almost to say, ‘This poor kid thinks he’s going to play hockey in a few months.’”

The doctor told Volpatti that recovery would take a long time. He wasn’t going to be playing hockey in a few months. In a few years, maybe he could look into playing hockey in a non-competitive environment, but that’s all.

“For me, my career was over in that moment,” recalls Volpatti. “I accepted responsibility for what I’d done, in a way, and I was just thankful that I’d make a full recovery eventually.”

As Volpatti turned the page on his hockey dream, though, his thoughts were full of negativity. He was in constant pain and now a key part of his life had been taken away. He tried to turn his thoughts to what he could do next — he could still go to college and get his education and hopefully find a new dream or life goal.

"He's burnt himself to a crisp."

That’s when he got a phone call from the last person he expected — a college hockey scout. A Division I hockey scout at that.

Volpatti’s coach with the Vipers got a call from an assistant coach at Brown University. They were looking for a certain type of player — his exact words were, as Volpatti recalls, “Someone that can put the fear of God in the defencemen of the Ivy League.”

“I have the perfect guy for you,” said Volpatti’s coach. “There’s just one problem — he’s burnt himself to a crisp.”

Volpatti, still fully wrapped up like a mummy, had his parents hold the phone up to his ear to have the conversation he dreamed of having for years with an NCAA coach. Only, there was no scholarship offer at that point, just an open-ended hope that he might play again someday and maybe a Brown scout could see him when he does.

It seemed like a formality — a nice gesture from a hockey coach to wish him well in a dark time in his life. But it was also a spark of hope.

“I just remember thinking, I've worked my whole life to just talk to one of these scouts and here I am, and look what I've done to myself,” says Volpatti. “I remember I started to ask questions. I started asking, why can’t I play hockey?

“Well, there was a big list.”

There was a risk of infection. The skin grafts would be too fresh and too painful. He couldn’t even sweat from large areas of his skin, which would cause complications. He would need to wear a full bodysuit for two years. And the list of reasons why he couldn’t play hockey went on and on.

“I remember thinking, those reasons aren’t good enough,” says Volpatti. “If you tell me it’s going to hurt, it can’t be any worse than what I experienced the first two weeks in the burn unit.”

"My mind was all I had."

Volpatti began to visualize getting healthy, literally imagining his body healing at the cellular level. It allowed him to reframe the pain in his body from a negative to a positive — after all, wasn’t the pain just a sign that his body was fixing itself? It was a mind-over-matter situation and he resolved to be stronger mentally than his body was weak.

“I was bedridden, I couldn’t move, and my mind was all I had,” says Volpatti. “I just flipped that switch. I said, if I’m gonna get out of this hospital so I can play hockey, I need to focus on what I want. I essentially lived in an alternate reality for that last month in the burn unit and it got me out of there a lot sooner than I was supposed to.

“I would paint a picture in my mind and create an experience. First thing I visualized was my body healing to reframe the pain…The second was walking out of that hospital…The third thing I visualized was stepping on the ice for the home opener for the Vipers in the Fall. And the guiding star for all of it was signing that commitment letter to Brown University.”

It was like he was creating a movie in his mind and it took him away from the constant pain and the mundane reality of being bedridden. When he was finally able to leave his bed, he pushed his body to its limits, only slowing down when his body forced him to — he had an emergency appendectomy 10 days before Vipers training camp, where they had to cut through his skin graft to get to his appendix.

"I was holding on by a thread."

When the home opener for the Vipers came around, incredibly, Volpatti was in the lineup.

“If people would have known what I looked like under my hockey gear, they would have been baffled,” says Volpatti, describing the various creams and non-stick meshes that covered his skin grafts and still open burn wounds, along with the full bodysuit that covered his legs and torso. “I eventually got that scholarship to Brown but I was holding on by a thread. I mean, I could barely walk to and from the rink and I was on crutches.”

Volpatti’s physical style on the ice meant he was in agony with every hit and the skin grafts on his thighs and inability to train during the summer caused some instability in his legs and pelvis. Despite it all, he managed to put up 14 points in 25 games, hanging on until he signed his commitment letter to Brown before shutting down for the rest of the season.

Against all odds, Volpatti had achieved his dream of an NCAA scholarship and was on his way to one of the top schools in the U.S. But the lessons he learned while recovering in the burn unit helped him achieve an even bigger dream — playing in the NHL.

“It was the greatest gift I’ve ever received, in a way,” says Volpatti now about the fiery accident that nearly ended his hockey aspirations, though he hastens to add that everyone else should avoid lighting themselves on fire to learn the same lessons he did.

"I just enjoyed being a student-athlete."

Just like in Vernon, Volpatti reset in his first year at Brown back to his default mode: hitting, skating, and fighting. Only, there’s no fighting in college hockey, so he had to stick with the hitting and skating, along with mixing it up in post-whistle scrums.

At this point, Volpatti was happy to be living his dream. He kept his burn injury to himself, worked hard at working his way up the lineup, and dove into his classes in human biology, discovering fascinating facts about the brain and body that helped him better understand the experience he had gone through in the burn unit.

“I got to learn about the brain and neuroscience and neuroplasticity,” says Volpatti. “I just enjoyed being a student-athlete but I thought that was it for hockey for me. I figured I would go into medical school or do my masters.”

After his third year at Brown, however, he was informed by one of his assistant coaches that some AHL teams had asked about him and was told that if he worked on his game, he might someday play in the NHL. It was a lightbulb moment for Volpatti, who had never even entertained the possibility of playing in the NHL, not since he was a kid playing road hockey in Revelstoke.

Volpatti decided that if he could recover from a devastating burn injury to play hockey again, then he could play in the NHL. He applied the same visualization technique that got him through the weeks of bedridden pain in the burn unit, but this time the movie that played in his mind was him pulling on an NHL jersey — a Vancouver Canucks jersey, naturally, for a kid who grew up in B.C. — and skating in front of thousands of fans in an NHL arena.

“I had a ‘you better cut my legs off before I stopped trying’ mentality,” said Volpatti, who lived at the rink that offseason, developing the skills he needed beyond hitting, skating, and fighting.

"The credits don't roll in my head — this is happening for real."

Volpatti broke out in his senior year. He was named captain of the Brown Bears and scored 17 goals and 32 points in 37 games. Instead of just AHL teams asking about him, Volpatti became one of the most sought-after college free agents, with multiple NHL teams eager to sign the hard-hitting winger.

The Canucks were one of the first teams to show interest and it was a natural fit. There was no room in the Canucks lineup for a traditional enforcer, the type who couldn’t skate or play the game, but a player like Volpatti who had the speed to go with his size was exactly the type of depth forward they were looking for.

For Volpatti, it was like the movie in his mind had come to life.

“It was pretty surreal,” says Volpatti. “I think back to being in that burn unit in Vancouver and being a Canucks fan growing up — it was a pretty wild journey.”

Volpatti started his professional career with the Manitoba Moose in the AHL, but he got called up to Vancouver in his rookie year, playing 15 games with the 2010-11 Canucks, arguably the best team in franchise history. Not long after, he would be in the press box as one of the Canucks’ black aces as they chased after the Stanley Cup.

“I remember going out on that ice for that first game. You’ve got to remember that I had done this thousands of times in my head and it was finally happening,” says Volpatti. “But now the lights don’t go out and the credits don’t roll in my head — this is happening for real.”

Volpatti stuck with the Canucks out of training camp the following season, eventually playing parts of three seasons with the Canucks before being waived in 2013 and claimed by the Washington Capitals. A couple of years later, a hit from behind in a game against the New York Islanders sent him headlong into the boards and his NHL career came to a crashing halt.

With a major disc rupture in his neck that required fusion surgery, Volpatti couldn’t mind-over-matter his way back to the ice.

“The difference was I couldn’t make my burn injury any worse,” says Volpatti. “With the neck injury, there were major complications — life-changing complications where I could make it a lot worse.”

Defying the odds

The identity crisis that followed from having to finally hang up the skates — a decade after originally being told that he wouldn’t play competitive hockey again — was even more difficult than when Volpatti was lying in the burn unit in Vancouver. But it was those same lessons of mental perseverance that he learned in the burn unit that helped him get through it.

Years later, as a performance coach and speaker, Volpatti is now teaching others the visualization techniques that helped him get through his darkest moments. He spent two years writing his first book, Fighter: Defying The NHL Odds, which comes out October 25, detailing his incredible journey through adversity.

As part of his book launch, Volpatti will be coming back to Vancouver, holding a book signing at the Canucks Alumni Luncheon on Nov. 17 at the Fairmont Hotel Vancouver, then at the Canucks game against the Los Angeles Kings at Rogers Arena on November 18.

After his experience in the Vancouver General Hospital burn unit, Volpatti knew he wanted to give back in some way, so he will be supporting the British Columbia Professional Fire Fighters' Burn Fund. For the first 54 days — his number in Vancouver — he will be donating 40% of the profits from the book to the Burn Fund, to remember the 40 per cent of his body that was covered in second and third-degree burns.

“A big part of why I wrote the book was to help people,” says Volpatti. “If I can help people by sharing this with them and making a difference in people’s lives, then I’m doing a disservice by not writing it.”