Three years ago, way back in 2015, Jim Benning made some big changes to the Canucks roster in the off-season. He traded away Kevin Bieksa, Eddie Lack, and Zack Kassian in a four-day span at the end of June, but his biggest move came a month later.

Benning traded Nick Bonino, Adam Clendening, and a second-round pick to the Pittsburgh Penguins for Brandon Sutter and a third-round pick. Before Sutter played a game for the Canucks, Benning signed him to a five-year contract extension worth $4.375 million per year and referred to him as a “foundation piece” for the future of the franchise.

Coming off a first-round playoff loss to the Calgary Flames, Benning believed the team needed a different look to succeed in the playoffs, and Sutter was a big part of that. He saw him as a potential second-line centre who was “going to be in our next wave of core players,” whose “best hockey is still ahead of him.”

“You win with players like Brandon Sutter,” said Benning before the 2015-16 season. “I’m not comparing him to Patrice Bergeron, but when I was in Boston, Bergeron was a great two-way player for us. Look at Jonathan Toews. That’s how you win in the playoffs.”

There’s just one problem: the Canucks haven’t made the playoffs. It’s possible the Canucks will never get to test the hypothesis that you win in the playoffs with players like Sutter.

The Canucks finished 28th in the NHL in Sutter’s first year with the team, while setting a new franchise low in goals scored. They did even worse in his second year: 29th, with eight fewer goals. Now, in his third year, the Canucks will once again miss the playoffs and could finish even lower in the standings. They could possible even be the first team in NHL history to finish 31st.

Fortunately, they won’t set a new franchise low in goal-scoring, largely thanks to Brock Boeser.

Let’s be clear: It’s not really Sutter’s fault that the Canucks haven’t made the playoffs and that he’s not the player that Benning thought he was when he acquired him. Hockey is a team game and Sutter is who he is.

Under Travis Green, Sutter’s role has come into clearer focus, as the team has ceased trying to turn him into a top-six forward. Instead, Sutter has happily thrown himself into the thankless role of shutdown centre. This means he has had little opportunity to put up points, tasked instead with taking the bulk of the defensive zone faceoffs and playing on the penalty kill rather than the power play.

While zone starts aren’t everything — the vast majority of shifts in a hockey game start “on the fly” rather than with a faceoff — the extreme cases are still interesting. At the very least, they can tell you how a coach views a player.

Sutter is one of those extreme cases. Only one player in the NHL has a higher ratio of defensive zone starts to offensive zone starts: his occasional linemate, Brendan Gaunce. Sutter has been on the ice for almost exactly three times as many defensive zone faceoffs as offensive zone faceoffs.

Only Ryan O’Reilly of the Buffalo Sabres averages more than Sutter’s 9.7 defensive zone faceoffs per game, which includes shorthanded situations. On the penalty kill, Sutter leads the league in faceoffs taken by a wide margin: 3.2 per game, with Mikko Koivu’s 2.7 per game the next highest.

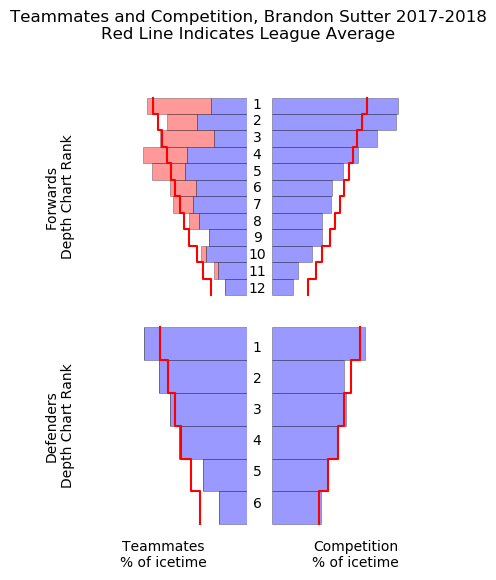

On top of that, Sutter has been hard-matched against the opposition’s top lines all season. You can see from this visualization of Sutter’s competition and teammates from HockeyViz, that Sutter has faced the top three forwards on the opposition far more than average this season.

Given that usage, Sutter has managed to largely limit the offence of his opponents, even if the Canucks have given up some offence of their own in the process. With Sutter on the ice at 5-on-5, the Canucks have allowed 1.93 goals against per hour, the second lowest rate of goals against on the team behind Brendan Gaunce.

It’s a role that fits Sutter’s skill set, if not his contract, and a role that would potentially be an important one in the playoffs. But will the Canucks will get back to the postseason within the next three years before Sutter’s contract is up?

Actually, that’s just one question; another might be whether the tradeoff in goal prevention when Sutter is on the ice with such extreme usage is worth the offence you give up. Is that tradeoff part of the reason why the Canucks have struggled so much?

The Canucks have been out-attempted, out-shot, and out-scored with Sutter on the ice, which isn’t too surprising given his usage. He’s having the worst season of his career offensively: his 0.93 points per hour at 5-on-5 is the lowest of his career. The question is not about whether another player would perform better given the same usage, as no one else in the NHL has usage quite that extreme (except for, as mentioned, Brendan Gaunce). The question is whether that ice time could be parceled out to more offensively gifted players that could outscore the opposition instead of just limiting their offence.

The big problem, of course, is that the Canucks lack those players.

As Alex Novet has demonstrated, hockey is a “strong link” game. The popular phrase, “You’re only as strong as your weakest link,” just isn’t true for hockey.

I first became familiar with the concept of strong and weak games in The Numbers Game, a book by Chris Anderson and David Sally on soccer analytics. In it, they define a strong link game as one where the team with the best player usually wins. In contrast, in a weak link game, the team without the worst player usually wins.

Anderson and Sally figured out that soccer is a “weak link” game: teams can improve more by upgrading their weakest player than they can by upgrading their best player. In soccer, one strong player can’t dominate a game; instead, the team that doesn’t have the worst player generally wins.

Novet discovered that hockey is a “strong link” game: the team with the best player(s) usually wins, rather than a team with stronger depth. As an example, if you pit a team with the Tampa Bay Lightning’s first line and three lines made of replacement-level fourth-liners against a team entirely composed of third-line players, the team with the elite talent on the Lightning’s top line will usually win.

As this applies to Sutter, he’s a very good “weak link.” But the Canucks’ biggest need is better “strong links.”

Given the Sedins’ decline, the only legitimate star on the Canucks is Brock Boeser, with a nod towards Bo Horvat on the bubble. As we’ve seen this season, that’s not enough to move the needle.

Veterans like Sutter, Loui Eriksson, and Sam Gagner haven’t been enough to get the Canucks back to the playoffs, so the team will need young prospects to make the team and immediately become difference makers. The development of players like Elias Pettersson, Adam Gaudette, Olli Juolevi, and Jonathan Dahlen is crucial.

If one or two of those prospects can become the Canucks’ new “strong links,” that will likely determine whether the Canucks will see the playoffs before the end of Sutter’s contract.