The Vancouver Canucks’ forwards should be significantly better next season compared to last season. Not only are Brock Boeser and Elias Pettersson 100% healthy and entering the prime of their careers, but the Canucks also added a bonafide top-six winger in Conor Garland.

Add that to the hopeful progression from Nils Höglander and the arrival of Vasily Podkolzin in Vancouver and there are a lot of reasons to be excited about the Canucks’ offensive potential.

The big question is how good will they be at keeping the puck out of their own net.

The Canucks’ overhaul on defence this offseason means they will definitely look different on the blue line. Oliver Ekman-Larsson will replace Alex Edler on the left side, which may or may not be an upgrade.

On the right side, the big addition was 28-year-old Tucker Poolman, who the Canucks signed to a four-year deal worth $2.5 million per year.

Poolman has history with Boeser, as they were teammates at the University of North Dakota. What he doesn’t have is a long history in the NHL. Despite already being 28, he’s played just 120 games across three seasons in the NHL. Still, despite the limited track record, Poolman played in the Winnipeg Jets’ top four this past season and the Canucks are hoping he can do the same for them.

Most importantly, the Canucks believe Poolman can bring an element to their defence they lost last season.

“We just think he’s a good fit for our team,” said general manager Jim Benning. “Losing Chris Tanev hurt us…we think Tucker Poolman has some of that in him.”

Considering just how good Tanev is defensively, those are some mighty big skates to fill and there are reasons to be skeptical that Poolman can do it.

Poolman has some ugly numbers but are they entirely his fault?

Among the 171 NHL defencemen who played at least 500 minutes at 5-on-5 last season, Poolman ranked 148th in the rate of expected goals against and 162nd in the rate of high-danger chances against, according to Natural Stat Trick. Chris Tanev, incidentally, ranked first in both of those categories.

This isn’t a new development either. Poolman was even worse in expected goals against and high-danger chances against in his previous season, one where he primarily played on the third pairing.

It’s definitely concerning that the player the Canucks hope can play a shutdown role similar to Tanev has given up dangerous scoring chances at among the highest rates in the NHL over the past two seasons.

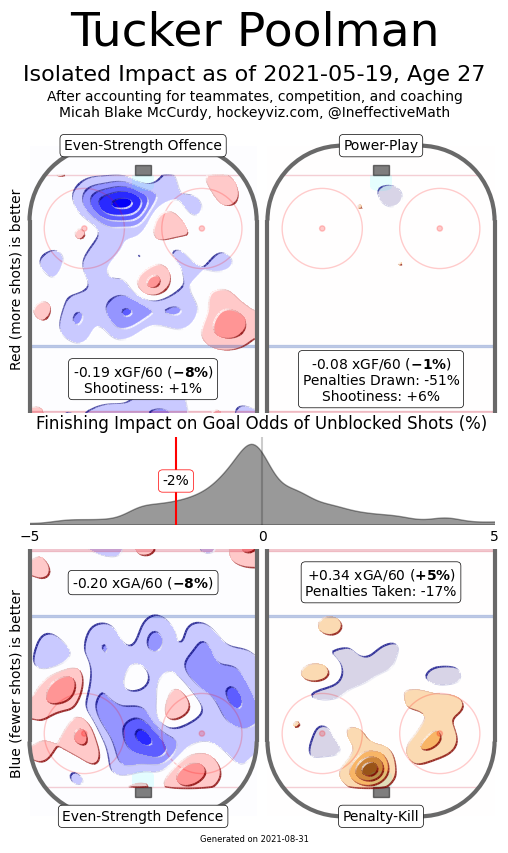

It would be simplistic, however, to say that hockey’s advanced statistics all call Poolman bad defensively. In fact, one particular statistical model suggests that Poolman is quite good in his own zone. Poolman’s isolated impact heatmap from Hockey Viz, which uses a model created by mathematician Micah Blake McCurdy, is rather high on Poolman’s defensive ability.

While the heatmap illustrates how ineffective Poolman is at creating offence — something also reflected by his 1 point in 39 games last season — it also suggests that Poolman is quite effective at limiting dangerous scoring chances. That wide swathe of blue in front of his own net indicates a lower than average number of shots from that very dangerous area of the ice.

So, how does this compute? The number of high-danger chances given up by the Jets when Poolman was on the ice is simply a fact. It doesn’t go away. But it’s a fact that might be missing some vital context.

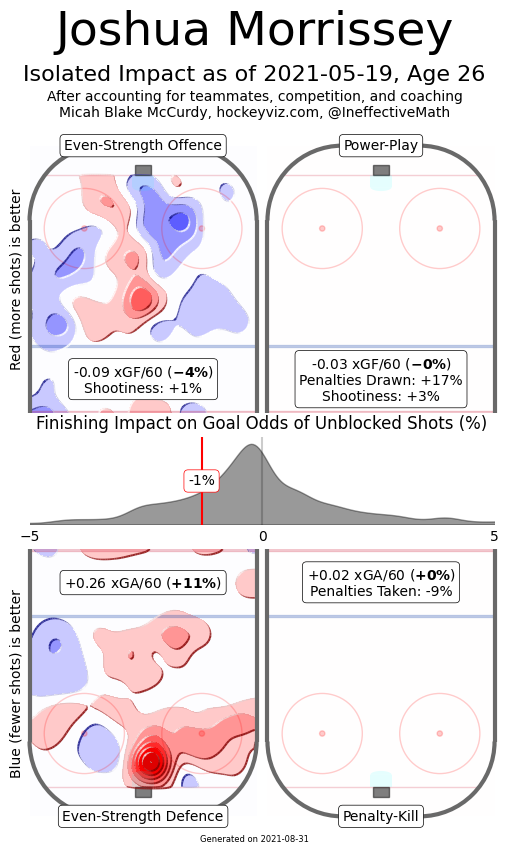

Turning back to McCurdy’s model, we can see what that context might be when we look at Poolman’s most frequent defence partner last season: Josh Morrissey.

Looking at the mountain of red in front of his own net representing an above-average number of shots from that area, it’s clear that the model places the vast majority of the blame for all of those high-danger chances on Morrissey, not Poolman.

If we turn back to high-danger chances against, Morrissey was 169th among the 171 defencemen who played 500 minutes at 5-on-5 last season. Perhaps Morrissey was truly dragging down Poolman.

Before celebrating and asserting that Poolman will surely get better results next season now that he’s away from Morrissey and the Jets, there’s one other issue. The two defencemen on the Canucks that Poolman is most likely to play with, Quinn Hughes and Oliver Ekman-Larsson, were 166th and 167th in high-danger chances against.

Still, it’s encouraging to see at least some reason to be optimistic about Poolman’s defensive game heading into next season.

Might there be more reasons to be optimistic? Let’s dive a little deeper into the pool, man.

Shoehorned into a larger role or a perfect fit?

The Athletic’s Murat Ates describes Poolman as someone “whose size, mobility and puck-moving look terrific in a third-pairing role but whose defensive shortcomings stand out against the NHL’s elites” and who the Jets “shoehorned” into a role he wasn’t ready for.

For Canucks fans, the question becomes whether Poolman is ready now for that larger role. He wasn’t able to compensate for Morrissey’s defensive issues on the Jets’ top pairing — can he compensate for the defensive issues of Hughes or Ekman-Larsson?

To get a better picture of Poolman as a player, I watched some of his games from last season. What I saw made me cautiously optimistic but also highlighted some of Poolman’s shortfallings.

Unlike previous deep dives on Conor Garland and Oliver Ekman-Larsson, there likely won’t be as many video clips of Poolman. Regrettably, a stay-at-home defenceman conservatively backing up into the neutral zone to prevent a dangerous scoring chance on the rush doesn’t make for a compelling clip.

In many ways, that’s a good thing. You want a defensive defenceman to be largely unnoticeable on the ice. When a defensive defenceman is effective — in the right position on the ice, taking away passing and shooting lanes, tying up their man in front — nothing happens. The more nothing that happens, the better they’ve played.

When Poolman plays a simple game, that’s what happens: nothing. He’s effective when he’s battling hard in front of his own net, getting inside position and working to keep opposing players out of his goaltender’s eyeline and with their sticks tied up. On breakouts, he’s most effective when he’s making a short, simple pass.

Nothing fancy. Simple is best.

Mind the gap control

The Canucks could use a little simple and solid defence on the backend, so a 6’2” defenceman whose mobility allows him to keep a good gap should theoretically help out a lot.

Against the rush, Poolman’s gap control was just fine, like this play against Auston Matthews where he keeps the Toronto Maple Leafs star from cutting inside, then leans on him to guide him into the boards.

Similarly, there’s this play where Poolman keeps Alex Kerfoot to the outside as he comes down the left wing, forcing him to take a low percentage shot.

You can see some good habits in his positioning on this 2-on-1, as he completely takes away the pass, then is able to pivot and pressure the shot.

Considering that’s Joe Thornton with the puck, a guy who loves nothing more than passing the puck, forcing him to shoot is a decent accomplishment by Poolman. The glove save from Connor Hellebuyck certainly helps.

The one major concern that developed the more I watched Poolman was just how passive and reactive he was. While he kept a good gap, he rarely forced the issue for opposing players. It was rare to see him step up at the blue line to prevent a zone entry or to cut off the boards and throw a hit to separate a player from the puck.

More often than not, he would allow the zone entry, but keep the player and the puck to the outside.

That’s all well and good, to a point, but it really seems like he has the size and skating ability to be more assertive and make opposing forwards uncomfortable on the rush. Instead, opposing forwards frequently felt perfectly comfortable attacking his side of the ice to gain the zone.

Perhaps that’s a coaching issue or perhaps that was a lack of confidence when facing elite forwards barrelling down the wing. The optimistic view is that’s something he can adjust in Vancouver.

A net-front presence

In-zone defending was a mixed bag. On the one hand, it was great to see him asserting himself in front of the net and making it easier for his goaltender to see the puck.

When he had a man in front, Poolman made life a little more miserable for that player. Most importantly, he always looked to tie up the stick of his check in front, making it difficult to get tips and rebounds. It looked like a legitimate strength of his game.

This particular play was one of his best sequences. Off a defensive zone faceoff, Poolman took his man to the net and got inside position on him. As his check switched sides with his stick, Poolman did as well, getting in position to block the shot and clear the puck to the boards. As an added bonus, a moment later Poolman used a quick stickhandle to evade pressure and make an outlet pass for the zone exit.

That’s Poolman at his best in the defensive zone.

Unfortunately, when things got a little more complex — a defensive breakdown by a teammate or elite opposition creating chaos — Poolman had a tendency to get a little lost.

Here’s an example against the Leafs. Poolman is at the top of the screen with Matthews behind him. As Matthews cuts across the slot, Poolman loses contact with him and ends up chasing him around the slot, allowing him access to the front of the net.

Nothing comes of the play, but it’s not a good sign to see Poolman chasing his man like this and it speaks to Ates’ assessment of Poolman’s “defensive shortcomings” against elite competition.

In a third-pairing role facing bottom-six forwards, the defensive structure is fairly simple because the opposing forwards generally attack in simple ways. They typically get a man to the front of the net and look to create shots with traffic. Poolman can excel against that type of attack, because he can battle his man in front, get into shooting lanes, and prevent scoring chances in tight.

That doesn’t always work against more creative forwards, who are looking to create more dangerous chances with their elite skill and playmaking ability. A defenceman can’t just rely on battling and shot blocking, but has to read the play and anticipate what those forwards might do.

The Jets’ team defence let Poolman down

All that said, Poolman’s struggles against elite forwards are not entirely his fault. When you’re defending against someone like McDavid or Matthews, it’s a team effort. All too often, Poolman’s teammates let him down.

Take this goal by Jesse Puljujarvi as an example. Poolman is matched up against McDavid and has been doing an admirable job of keeping him to the outside. The issue comes when Kyle Connor leaves Puljujarvi open in front to try to help Poolman. It’s the worst thing he could’ve done, as McDavid immediately feeds Puljujarvi for the goal.

There's only so much that Poolman could do to prevent the Pool Party.

There seemed to be some major issues with the Jets’ defensive systems or with the players’ ability to execute those systems.

If Poolman was at his best defending the house in front of the net, he was at his worst when he had to shadow his man around the zone in man-on-man coverage. That was partly because it played against his strengths, but also because seemingly every other Jet on the ice was far worse at defending the front of the net than he was.

A player has to be able to trust that everyone else in the defensive zone is going to be engaged and taking care of their responsibilities. When they don’t it all falls apart.

Take this play, for example, where Poolman is staying on the puck in the corner. He's doing a fine job — he's not able to disrupt the cycle, but keeps the pressure on and stays on his man. But look behind him, where Pierre-Luc Dubois just leaves his man alone in front to stand in the slot, leaving Morrissey with two men in front of the net.

Nothing comes of it, but it’s emblematic of something I saw frequently while watching the Jets: players not rotating and covering for each other in defensive zone coverage.

Of course, the Canucks’ defensive zone coverage hasn’t been much better. From what I saw, a lot of the defensive breakdowns could be pinned on other players but Poolman might not get much help in that area in Vancouver either.

No transitory

A defenceman’s job doesn’t end with defending, of course. While Poolman was generally good in his own zone, particularly when tasked with defending the front of the net, moving the puck up ice was a bit more of a challenge.

At his best, Poolman kept things simple with short passes to teammates coming low in support. He didn’t seem fazed by forechecking pressure and looked to relieve that pressure with a quick pass to his defence partner, sometimes with a little deception to throw off the opposing forward.

You shouldn’t expect tape-to-tape stretch passes from Poolman. From the shifts I watched, most breakout passes that had to cross more than one line were either off the mark or were picked off or deflected by the opposing team. It’s just not a strength of his game.

It seemed to be a limitation of which he was aware. Under pressure in the defensive zone, he typically preferred to go off the glass and out rather than make a riskier play and he generally deferred to his defence partner on breakouts. Sometimes his go-to bank off the boards backfired, as in this turnover against the Canucks.

When he had time with the puck, Poolman was a little better at using deception to open up passing lanes, like this delayed pass against the Canucks.

Poolman was better, actually, when he skated the puck out himself. He’s a decent skater, particularly for his size. He just rarely chose to skate the puck up ice.

Here’s one instance against the Leafs, as he adeptly escapes a forechecker, sees that he has room to skate, and jumps up through the neutral zone, even getting in on the forecheck, though he quickly abandons that to get back to safety at the point.

There’s a reason why Poolman only had one point this last season and his underlying analytics show a player with limited offensive upside. With his limited transition game, he rarely sparked dangerous rushes and, when the puck was in the offensive zone, Poolman played it safe as a rule.

Given the choice between trying to hold the line or backing up into the neutral zone, Poolman backed up if there appeared to be any risk whatsoever. A pinch down the boards was rare.

He was the safety valve for the more risk-taking play of Morrissey. If there is more offensive potential in Poolman’s game, it’s unlikely to come out in Vancouver if he plays a similar role for Hughes. If Poolman plays with Ekman-Larsson instead, he’ll likely be in a pure shutdown role, so offence is again unlikely.

What’s the verdict?

Poolman looks like a fine defensive defenceman. While he’s not at the level of someone like Chris Tanev, he’s perfectly capable of playing a safe, stay-at-home game that leverages his size and reach to defend the front of the net.

There are statistics that suggest that some of Poolman’s apparent defensive struggles could be pinned on teammates instead and the eye test seems to back that up. At the same time, Poolman does have some legitimate issues when it comes to reading and reacting against elite competition.

I have two primary concerns, one of which might be fixable; the other probably isn’t.

The first concern is his passive approach to defending the rush, where he keeps a good gap and takes away the middle of the ice, but isn’t assertive enough to prevent zone entries or make life difficult for opposing forwards. Against lesser competition, that can be sufficient — elite players will take everything they’re given and make something more of it.

With more confidence playing against tough competition in a top-four role, along with some coaching adjustments, perhaps Poolman could use his size and skating to be more assertive and erase that concern.

The other concern is his complete lack of transition and offensive game. While Poolman has decent enough skill with the puck and can make a good first pass, he provides practically no value offensively, whether in puck possession or creating chances. That shows up both in the numbers and when watching him play.

While he likely will be able to score more than the one point he had last season — he had 16 points in his previous season — his limited transition game isn’t ideal for a Canucks team that already struggled to transition the puck up ice last season.

The clear intention of the Canucks is to line up their top four with an offensive defenceman on the left side and a defensive defenceman on the right. Hughes and Ekman-Larsson will have to handle most of the transition duties for their pairings, while Poolman and Travis Hamonic will be their safe, stay-at-home partners.

Will that work or will Poolman’s lack of transition game hurt the amount of offence his defence partner is able to create? That remains to be seen.