Over 200 hockey players get picked in the NHL Entry Draft every year. Hundreds more dream of being one of the few undrafted players to buck the odds and make the NHL.

Of those hundreds of players each year, only a few dozen will go on to have a significant NHL career. Around half of the players that get picked in the draft never even play an NHL game. The question for those players is what happens next?

Some of those players toil in the minor leagues, hoping to someday work their way up to the NHL. Others head overseas to play professional hockey in Europe or Russia. Still others step off the ice and become coaches or scouts.

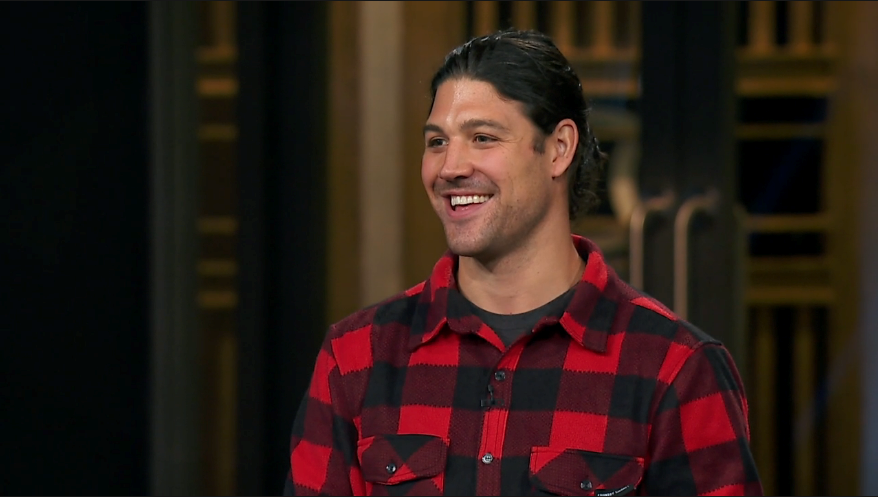

Sawyer Hannay took a different path, one that led him to Dragon’s Den and a $150,000 investment in his company.

10 years ago, Hannay got the biggest surprise of his life when he was picked in the 7th-round of the 2010 NHL Entry Draft by the Vancouver Canucks. The 6'4" defensive defenceman had been told he should go to the draft in Los Angeles that year by his agent, who insisted he was likely to get picked. Instead, Hannay was at his high school graduation, which was on the same day as the draft.

“My agent was telling me, ‘Sawyer, you’ve gotta go to the draft,’ but in my heart, I still didn’t really believe it,” said Hannay. “I just wasn’t convinced I was going to be picked and I was okay with that, so when I got the call I was at my own graduation party. It was just insane excitement.

“It went from my parents being proud of me that I managed to get through high school to I was drafted to the NHL, so it went from zero to 100 really quick.”

Hannay grew up in Rexton, New Brunswick, a small town of just 800 people, so that heightened the excitement. For Hannay to even play Major Junior with the Halifax Mooseheads in the QMJHL was an accomplishment — getting drafted by an NHL team seemed like a dream.

I was obsessed with hockey

“As long as I can remember, as long as I could skate, I wanted to play in the NHL,” said Hannay. “I used to play ball hockey in my driveway with rollerblades by myself until the wheels wore out. I was obsessed with hockey. My father made an outdoor rink and I used to skate around and narrate myself playing in the NHL.

“But nobody from our area had ever done it, so it didn’t really seem attainable. And then, all of a sudden, here I was: I was drafted. I was skating with NHL stars, because Vancouver had such a good team at the time.”

Hannay waxed nostalgic about pulling a Canucks jersey over his head for the first time and meeting Roberto Luongo, Ryan Kesler, and the Sedin twins — “I was a little kid living my dream skating with these legends.” Even at the prospect camps he attended with the Canucks, a couple of players jumped out in his recollection.

“Chris Tanev was on our team, what a player that guy turned out to be,” he said. “And [Antoine] Roussel was there. I remember battling with that guy in the corners and I knew he was making the NHL just by the way he competed.”

That same future wasn’t in the cards for Hannay, however. In his third season in the QMJHL, Hannay suffered a setback that derailed any chance of him making the NHL: a concussion.

“We were discussing a potential contract early in the season,” said Hannay, “and I took a really bad concussion. I couldn’t read, I couldn’t write, I was in rough, rough shape. I got out of shape. That kind of sidelined the potential contract talks.”

Hannay wouldn’t go to another Canucks camp after that. He was working with Darryl Young, then an amateur scout in eastern Canada for the Canucks. Young became a mentor for Hannay, training with him in the mornings and teaching him what it would take to become successful in professional hockey.

“He went above and beyond,” said Hannay. “He taught me a lot of life lessons. I thought I was working hard and he showed a whole new level of that. I was his draft pick and he showed a lot of faith in me. He was unbelievable and he ended up getting me a tryout in the American League — his brother is GM of the Chicago Wolves. He got me a contract overseas as well. That was a Vancouver scout going above and beyond the call of duty for a prospect that wasn’t good enough to make the NHL.”

The end of a dream

The realization that the NHL dream was ending came slowly, first as his season in Europe coincided with the 2012-13 NHL lockout and European leagues were hit with a flood of NHL talent, then as he went through the grind of the ECHL with the Evansville Icemen. He saw some of the uglier sides of the business of professional hockey in Europe and the sheer number of players in the ECHL working towards the same limited number of jobs in the AHL and beyond.

“I was honest with myself. I knew how good everybody was, I knew where I fit in,” said Hannay. “It wasn’t easy to have that conversation with myself, but I understood it.”

So, Hannay went a different direction: playing hockey at St. Thomas University in Fredericton, New Brunswick, just a few hours from his hometown, while studying economics and business. The hockey player who “managed” to finish high school fast-tracked his degree because in the back of his mind he still wanted to pursue hockey.

“I finished it in two-and-a-half years because I wanted to be younger to play pro again. As we all know, the opportunities are better when you’re younger,” said Hannay. “But at the same time that I was accelerating this degree, I was also dipping my toes into the business world.”

When he graduated, Hannay was faced with a decision: go back to grinding his way through the lower levels of professional hockey in pursuit of his lifelong dream or find a new dream and a new passion in the business world.

Hannay turned away from hockey and founded his own company, Country Liberty. It was borne out of the years he spent away from his small town — he left at 16 to pursue his hockey dreams — that made him miss and appreciate his experience growing up in a rural area. His brand reflects that: rugged clothing designed for the outdoors.

“I was disappointed I didn't make the Canucks sure, but the lessons I learned and the experiences I had, I was grateful for,” he said. “I put those in my back pocket and I simply pivoted.”

Pitching to Dragon's Den

Hannay started out selling shirts out of his apartment while at university but grew the company into something a lot bigger: big enough to pitch to the investors on Dragon’s Den. His $2.5 million in sales caught their attention, though he faced some tough challenges during his pitch, particularly from one "dragon," Manjit Minhas, the stylish owner of Mihas Brewery, who didn't connect with his casual apparel. But even that proved helpful.

"She asked me a lot of pretty tough questions, some of them didn't make the air," said Hannay. "To be honest, I was in there for an hour and there's a lot that I don't actually remember just because it happened so fast and excitement was high, nerves were high. They asked a lot of insightful questions and even based on the questions they asked, I learned a lot too."

Ultimately, he impressed enough of the "dragons" to get several competing offers, ultimately accepting an offer of $150,000 for 20% of his company from Jim Treliving and Lane Merrifield.

Both Treliving and Merrifield are as far away from New Brunswick as you can get while staying in Canada. Treliving, the owner of Boston Pizza, lives in Vancouver. Merrifield, the creator of Club Penguin and school software FreshGrade, is located in Kelowna. Hannay sees them as the perfect partners to help him take Country Liberty coast to coast like Larry Robinson.

Unlike in hockey, where Canucks scout Darryl Young took him under his wing, Hannay hasn’t had a mentor in the business world.

“That was part of the attraction of Dragon’s Den,” said Hannay. “I would love to have a mentor to that degree. Those guys are the Roberto Luongos of the business world.”

While the deal hasn’t been finalized — Treliving and Merrifield are still doing their due diligence — but Hannay is optimistic that the deal will be made official soon. Then he’ll be working to grow his company into the very competitive world of outdoor clothing in Canada. Hannay wouldn’t have it any other way.

“I’m a very, very competitive person,” said Hannay. “I’ve worked jobs where there was no competitive aspect and I was miserable. I really crave that competition and that’s why transitioning from hockey to business was so natural for me. You’re not only competing with the obvious competitors, but you’re competing with yourself and challenging yourself every single day to get better.”

Of course, Hannay hasn’t completely left hockey behind. The difference is that instead of grinding his way up from the bottom, Hannay suddenly finds himself on top.

“This year with COVID, there’s no hockey, but I played for a local senior team last year, which was really, really fun,” he said. “I was a depth defenceman throughout my short professional and amateur career and to play on the local senior team, it’s nice to be the guy getting 30 minutes a game.”

Hannay laughed. “It’s kind of nice that after 20-something years of hard work, now I get to be on the power play.”