Picture the scene: it’s the third period and your team is down by a goal with less than a minute remaining in regulation. Your team has a faceoff in the offensive zone with the goaltender pulled for the extra attacker. If they can just win the faceoff, they have a chance to tie the game and send it to overtime.

The moment is tense. The entire outcome of the game comes down to this moment. All eyes focus on the two centres as they come together at the faceoff dot, desperately battling to win the puck.

And then the linesperson stands up, the puck still in his hand; he never dropped it. In a dreadful anticlimax to the tense moment, he points to his left to wave out your team’s top faceoff centre and delay the restart of the game.

But the tension mounts again. The two players come together at the faceoff circle and — oh now what? The linesperson stands up and waves out the other team’s centre too.

A lot of fans in that situation might think or say aloud, “Just drop the puck already!”

Why doesn’t the linesperson just drop the puck?

You have to wonder if NHL players have the same thought. Do they ever wish the linesperson would just get it over with and drop the puck?

“Sometimes, yeah,” said Vancouver Canucks centre Teddy Blueger with a wry smile. “When it gets out of hand, when they’re kicking out guys left and right and it slows the game down, it’s annoying for everyone; we don’t like that either.”

Of course, Blueger is a bit biased. As a centre who takes a lot of faceoffs, he wants every advantage he can get in the circle. More often than not, that means bending the rules to their breaking point and forcing the linesperson to keep him in check.

That means pushing the limits right from the start of the game.

“For the most part, you just do it and let them tell you to stop,” said Blueger. “If you’re doing something that’s a little more borderline, you just kind of do your best to try and get away with it and then if they blow it down, they tell you, ‘Hey, this isn’t going to fly tonight,’ then it’s no problem.

“But then you just want to make sure it’s consistent where the other team can’t do it either.”

In other words, the old sports adage, “If you ain’t cheating, you ain’t trying,” definitely applies to faceoffs. But with both centres — not to mention the other players on the ice — trying to get away with everything they can, there are a lot of reasons why a faceoff might get delayed.

That means it’s often not the linesperson’s fault that he isn’t dropping the puck.

“They have a hard job,” said Elias Pettersson. “There’s times when maybe I’m cheating and not letting them drop the puck. They’re just trying to keep it fair and square all the time.”

"Everybody knows what the rules are"

Understanding how linespeople keep the faceoff “fair and square” means turning to the NHL rulebook.

The portion of the rulebook that deals with faceoff procedures and violations, Rule 76, is about 3000 words long, but there are really only a few reasons why a centre gets waved out. Several of those reasons aren’t even a centre’s fault.

Rule 76.7 identifies four violations, and three of the violations primarily concern everyone other than the centre.

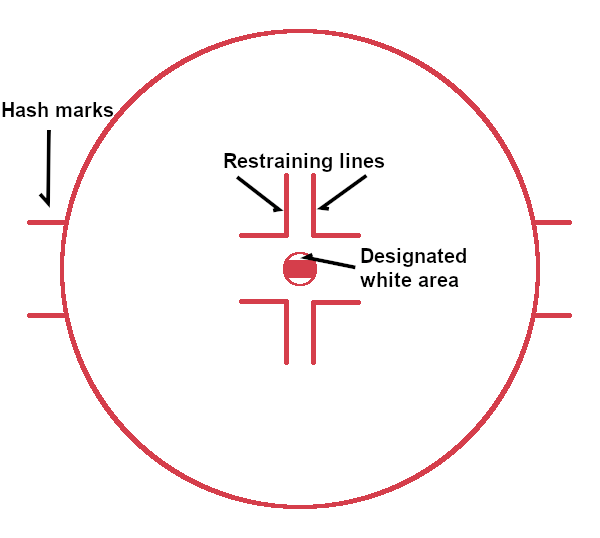

The first and second violations prohibit “encroachment” into either the faceoff circle or between the hash marks on the outside of the circle. The hash marks are the lines sticking on either side of the circle. So, if a winger sneaks over any of those lines to get an advantage, the centre will get tossed out of the faceoff through no fault of their own.

The third violation prohibits “any physical contact with an opponent,” a rule that is frequently tested by wingers but often just leads to the two jousting players being told to cool it without a centre getting tossed.

Finally, we get to the fourth violation, which encompasses all the things a centre actually has to be concerned with when they take a faceoff.

A centre has to “properly position himself behind the restraining lines…the toe of the blade of his skates must not cross over the restraining lines that are perpendicular to the side boards as he approaches the face-off spot.”

The restraining lines are the L-shaped lines on either side of the faceoff dot. You’ll frequently see players get reminded to move their foot back; repeatedly crossing that line is a common reason why a centre gets waved out.

“I think good communication solves a lot of those issues, so you know what to expect when you’re going in the draw,” said Blueger. “There are some different techniques with using your feet to block the other guy, and I think you just need to know whether or not the linesman’s gonna allow it or you’re gonna get kicked out for it.”

Once the skates are positioned correctly, the stick has to be in the right position too: “The blade of the stick must then be placed on the ice (at least the toe of the blade of the stick) in the designated white area of the face-off spot and must remain there until the puck is dropped.”

The faceoff dot is not a uniform colour: there are two small white semi-circles on both sides of the dot.

The one addendum to that rule is that the centre for the defending team has to put their stick on the ice first, except at centre ice, where the centre for the visiting team has to put their stick on the ice first.

That’s it. Those are the only two significant rules that a centre needs to abide by: keep your skates outside the restraining lines and put your stick in the "designated white area."

“The standard is simple,” said Pius Suter. “Everybody knows what the rules are and they enforce it that way. If you just dive in and don’t stop, you’re gonna get kicked out.”

So, what’s the problem?

Jumping the gun to win the draw

In World Athletics, such as the Olympics, an athlete is ruled to have “jumped the gun” if they move within 100 milliseconds — just one-tenth of a second — of the pistol being fired to start a race. In other words, even starting to sprint after the pistol is fired can be considered a false start because humans, in theory, cannot react.

The point is for sprinters to react to the starter’s pistol, not to anticipate it and try to get a head start on their competitors. If a sprinter jumps off the blocks within 100 milliseconds, they weren’t reacting, they were guessing.

The same principle applies to faceoffs. The point is for both centres to have their sticks on the ice and to react when the linesperson drops the puck.

In theory, that seems simple enough. In practice, however, centres are constantly trying to anticipate when the linesperson will drop the puck to gain an advantage on their opponent. Guessing correctly can be the difference between winning and losing the draw.

Guessing incorrectly gets you tossed from the faceoff circle.

Here’s an example from the Canucks’ game on March 1 against the Seattle Kraken, where Blueger got tossed.

Shane Wright places his stick in the “designated white area” first as the defending centre but Blueger doesn’t. Instead, he motions as if he’s about to put his stick in the white area but then immediately swoops into the dot, anticipating that the linesperson will drop the puck the instant his stick touches the ice.

The linesperson, however, never moves. He was waiting for Blueger to actually put his stick on the ice.

On some occasions, Blueger’s bet that the linesperson would drop the puck would have paid off, giving him a major advantage in winning the faceoff. On this occasion, it didn’t, and Kiefer Sherwood was called in to take the draw instead.

Hockey fans will sometimes complain about linespeople “pump-faking” on a faceoff — pretending to drop the puck to fool centres — but that doesn’t really happen. Instead, they will hold the puck still over the dot, wait for the two teams to line up appropriately, and drop it.

Don Cherry once ranted on Hockey Night in Canada about linespeople not dropping the puck, accusing them of faking out centres to “put a show on.” And yet, every cherry-picked example showed a linesperson simply holding the puck still while the centres jumped the gun. There wasn’t a single example of a linesperson trying to fake anyone out.

"Maybe I cheated"

The rules for faceoffs are clear, but there can often be a feeling-out process during the game to figure out where the line is going to be that particular night: whether they can cheat their skates in or get away with not actually putting their stick on the ice to gain an advantage

“Certain guys are more focused on the sticks, some guys more focused on skates,” said Suter. “Sometimes, when there was a meeting, it’s stricter.”

While players know the rules for faceoffs, that doesn’t mean they always know why they’ve gotten tossed from the circle.

“Sometimes they’ll just kick you out and start yelling for you to get out of the circle and you have no idea what happened,” said Blueger. “Just tell me the guy behind me went early, you know? Then it’s no big deal.”

That was a common refrain from the Canucks’ centres: they just want clear communication from the officials.

“You just make sure if you get kicked out, you know what you did wrong. It’s back and forth, not in a hostile way," said Suter, then added with a grin. "Well, most of the time. There’s always emotion."

"If you’re not doing well, you always feel like somebody’s doing something wrong,” he added.

Blueger and Suter both said that there’s a lot of communication that happens away from the faceoff circle, where they’ll often talk to a linesperson to clear up any confusion.

“There are times when you don’t really know why you got kicked out,” said Blueger. “I think the best guys to work with always take the time to explain it to you, whether it’s in the TV timeout — just have good communication. I think, for us, that’s a very frustrating thing where you’re getting kicked out or certain things are happening in the draw, and it’s not really communicated to you.”

“Sometimes we can get heated too,” he added. “But the best is when it’s level-headed, and you’ve got to be able to swallow your pride and apologize when you’re in the wrong.”

Of course, sometimes it’s not about a lack of communication but simply not liking the reason you got kicked out of the faceoff.

“I don’t always agree,” said Pettersson with a smile. “But then also, maybe I cheated.”