If you’re not familiar with Jon Bois, it can be tough to explain his appeal. He’s long been my favourite sportswriter, in spite of (or perhaps because of) the fact that he’s barely recognizable as a traditional sportswriter. He’s written about the best sports gifs, breaking sports video games with absurd scenarios, and speculative sports-adjacent fiction.

His largest project was 17776, which was ostensibly about what football would look like in the year 17776, but is really about boredom, empathy, the horror of immortality, and maybe what sports as a whole is really all about, as told by three intelligent space probes from the 20th century. It’s bizarre. It’s brilliant. It’s definitely not for everyone.

Bois has moved from articles to video over the past several years, with his Pretty Good series (“A show about stuff that is pretty good”) and his Chart Party series. Bois is the writer that has made me laugh the hardest I have ever laughed, but he also can create some excellent, serious content, such as the five-part documentary series on mixed martial arts called Fighting in the Age of Loneliness, which he has described as, “One of my favorite things I’ve ever made.”

Bois has a knack for turning the seemingly inane into the profound. His latest video in his Chart Party series, “The Bob Emergency: a study of athletes named Bob,” is no exception. What sounds like an absurd endeavour — exploring the history of athletes named Bob — delves into serious corners of the sporting world, touching on racism in turn-of-the-century boxing, an incredibly unlikely Hall of Fame pitcher, a basketball innovator, and the greatest season by a pitcher in major league history.

That’s just in part one of The Bob Emergency, which is over 42 minutes long. Part two should be coming out in a couple weeks.

In the initial overview, Bois mentions the 136 Bobs that have played in the NHL — not players named Bobby or Robert, but specifically Bob — but they don’t factor into part one in any major way. Perhaps an NHLer will feature in part two, but while we wait for that video to come out, I thought I’d take a look at some of the best Bobs in NHL history. Call it an homage to Jon Bois.

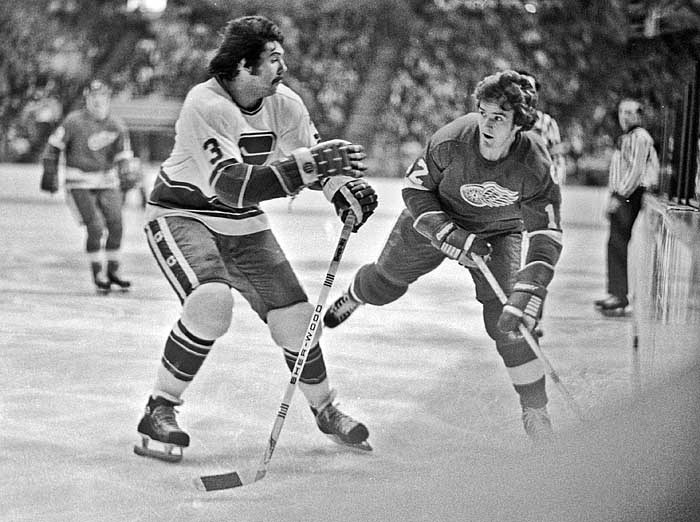

There have been seven Bobs in Canucks’ history, though two of them — Bob Hurlburt and Bob Cook — played just one and two games, respectively. Two others are goaltenders: Bob Mason, who played six games in the 1990-91 season and Bob Essensa, aka. Backup Bob, who split starts with Felix Potvin and Dan Cloutier in 2000-01. The three skaters that played full seasons with the Canucks were all defencemen: Bob Murray, Bob Manno, and Bob Dailey.

The best of the bunch was clearly Bob Dailey, who was one of the Canucks’ two first-round picks in 1973, along with Dennis Ververgaert. In a fun twist, Dailey was part of a run of three-straight Bobs taken in the 1973 draft: Bob Gainey was drafted eighth overall, then Dailey, then Bob Neely at tenth.

Dailey played just three-and-a-half seasons with the Canucks, but he was a standout performer, tallying 48 points in 70 games to lead all Canucks defencemen in 1974-75. He was also the league’s tallest player for the first few years of his career at 6’5”. He had size, skill, a heavy shot, and a mean streak: sort of a prototypical Chris Pronger.

Dailey was traded to the Philadelphia Flyers halfway through the 1976-77 season for Jack McIlhargey and Larry Goodenough. That return was clearly not, ahem, good enough for Dailey, who went on to become a star for the Flyers before a brutal ankle injury forced him into retirement at the age of 28.

Above, I mentioned Bob Gainey, who was drafted one pick ahead of Bob Dailey. Gainey is arguably the best Bob in NHL history.

Gainey was renowned for being a defensive specialist. He won four consecutive Frank J. Selke trophies as the NHL’s best defensive forward, but it’s not just that Gainey won the Selke: he’s arguably the reason the award even exists.

Gainey put up a modest number of goals and assists, consistently tallying around 30-45 points per season, but was considered one of the most important players to the Montreal Canadiens’ famed dynasty of the 70’s that won four consecutive Stanley Cups. It didn’t seem right that a dominant defensive player like Gainey was overlooked for the NHL’s major awards, so the league created a new one: the Selke.

Along with the Selke trophy and various All-Star Game appearances, Gainey also won the Conn Smythe Trophy as the MVP of the playoffs in 1979, when he had 16 points in 16 playoff games to go with his shutdown game.

During the 1981 Canada Cup, Soviet Union coach Viktor Tikhonov famously called Gainey “technically the most complete player in the world.” He was elected to the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1992 and was named one of the top 100 players in NHL history.

That’s a good Bob.

Aside from Bob Gainey, there’s just one other Bob in the Hockey Hall of Fame as a player: Bob Pulford.

Like Gainey, Pulford wasn’t flashy — that seems to be reserved for the Bobbys of the NHL — but was a reliable, two-way forward that was the bane of opposing players. Gordie Howe once described him as “one of my private headaches.”

Howe called him that because of his dangerous forechecking ability. Milt Schmit, coach of the Boston Bruins called him “a piece man,” because “any time he’s near you, he gets a piece of you.” He never won any major individual awards, mainly because he played before the Selke was created. He was, however, part of four Stanley Cup wins in the 60’s.

While Pulford was never an elite scorer like Howe, Bobby Hull, Frank Mahovlich, or Jean Beliveau, he was still among the top scorers of his era. During his career, he had the 14th-most goals of any NHL player, despite never tallying 30 goals in any one season. He was consistent and particularly known for his clutch scoring.

Pulford’s influence goes beyond his defensive excellence or his timely scoring, however. He had a major impact on the game of hockey in two significant ways. Both reflected his feisty nature and refusal to back down from a fight.

The first literally changed hockey rinks around the league. It became known as “The Battle that Divided the Penalty Box.” It was October 30th, 1963, and Pulford dropped the gloves with Canadiens defenceman Terry Harper. At the time, there was just one penalty box, shared by both teams. So, when Pulford and Harper got to the box, words were exchanged, then more fists.

Shortly after Pulford and Harper’s brawl in the penalty box, Maple Leaf Gardens was reconfigured to have separate penalty boxes. The Montreal Forum followed suit. Two years later, the NHL “suggested” that every rink in the league have separate penalty boxes for the two teams.

Pulford’s other major impact happened off the ice. He was one of the few players in the NHL who dared to challenge management. He once refused to play in an exhibition game because he didn’t yet have a contract, while other players without contracts did play. Nowadays, holding out is a little more common — William Nylander held out until the beginning of December this past season — but it was essentially unheard of at the time, even for an exhibition game.

That stubbornness and willingness to stand up for himself is likely what led to him becoming the first president of the NHL Players’ Association. Ted Lindsay and Doug Harvey formed the first NHLPA in 1957, but the team owners busted the union by trading or cutting players that joined, leading to players refusing to join out of fear.

Pulford, however, wouldn’t let that happen. He met with the owners and demanded they recognize the NHLPA as a legal entity or he would appeal to the Canadian Labour Relations Board for certification. Pulford got the official recognition for the union that he sought, as well as guarantees that no players would be punished for joining the union.

There’s one other Bob in the Hockey Hall of Fame in the builder’s category: Bob Johnson, who coached for six seasons in the NHL, winning the Stanley Cup in 1991. Beyond his NHL years, however, Johnson led the University of Wisconsin Badgers to three NCAA championships as head coach and the US national team for multiple years, including at the 1976 Olympics.

Johnson was known for his optimism and passion for hockey, illustrated by his catchphrase, “It’s a great day for hockey.”

Beyond his championships and passion, Johnson was an innovator. He emphasized conditioning and nutrition in ways that wouldn’t become commonplace until decades later. The drills he implemented at practice and the up-tempo playing style he promoted were harbingers of what was to come in the future.

Johnson was a teacher — literally. He was a high school history teacher, who would use a hockey stick as a pointer in his classroom. He earned his masters, then PhD in physical education from the University of Minnesota.

Other coaches eagerly borrowed from Johnson, who would readily admit that he had stolen many of his ideas from legendary Soviet coach Anatoly Tarasov and other overseas coaches that he observed while coaching Team USA. He was ahead of his time, particularly when it came to North America, and his fingerprints are all over the modern game.

Going back a little further, there’s Bob Goldham, who may not be a Hall of Famer, but he was a well-known figure to hockey fans, both for his years with the Maple Leafs, Black Hawks, and Red Wings, and also his years as an analyst and colour commentator for Hockey Night in Canada from 1960 to 1979.

As a player, Goldham was known as one of the best defensive defencemen of his era — again, the flashy scoring is for players named Bobby, not Bob — and was well known for his shot-blocking prowess, to the point that his nickname became “Second Goalie.”

“It is my opinion that Bob was the first in the league to implement the defensive style of blocking shots, which was tremendously complementary to the goalkeeper,” said Hall of Fame goaltender Glenn Hall, who played behind Goldham in 1955-56 with the Detroit Red Wings.

If you’re a fan of blocking shots, you have Goldham to thank. If you’re not, you have Goldham to blame.

The earliest Bob in NHL history that I could find is Bob Hall, who played eight games for the New York Americans during the 1925-26 NHL season. He recorded no points.

Hall was only the second American player to crack an NHL lineup, following in the footsteps of fellow Dartmouth alum George Geran. Hall and Geran were teammates on the Boston Athletic Association Unicorns before Hall left for New York.

The New York Americans predate the New York Rangers by one year and Hall played in their inaugural season. The Americans played in Madison Square Garden and were such an instant box office draw that Tex Rickard, president of the Garden, pursued his own franchise, starting the Rangers despite promises to the Americans that they would be the only team to play in the Garden.

The Rangers saw instant success, winning the Stanley Cup in only their second season, forever relegating the Americans to second best.

By the 1941-42 season, the Americans had lost some of their players to military service in the second World War. They were in debt, struggling to pay the players they still had, and playing in the shadow of the Rangers. After one season as the Brooklyn Americans, the team suspended operations, with hopes of relocating to Brooklyn a few years later. Instead, pressure from the Rangers and other factors meant the Americans were never reinstated.

The collapse of the Americans ushered in the Original Six era, but it didn’t work out well for the Rangers. Red Dutton, the coach and manager of the Americans, supposedly cursed the Rangers for what they did to the Americans, saying, “The Rangers never will win the Cup again in my lifetime.”

Sure enough, the Rangers didn’t win the Stanley Cup again until 1994, seven years after Dutton passed away.

Finally, it wouldn’t be right to celebrate the great Bobs throughout NHL history without mentioning Bob Cole. The legendary broadcaster called his first game with Hockey Night in Canada all the way back in 1969, overlapping with the career of Bob Goldham, and he called his final game this past season at the age of 85.

Bob Cole was a legend for good reason, with an instantly recognizable voice, a great feel for the natural rhythm of the game of hockey, and a sense for the big moments. More than anything, he loved hockey, and it came through in the excitement in his voice. When he saw great players make great plays, he could barely contain himself.

His voice punctuated big moments, with his often parodied pauses after almost every syllable. “Oh baby,” was his exclamation point. Most of all, however, he knew when to let the moment speak for itself, letting the roar of the crowd tell the story when no words were necessary.

So, there’s the story of seven Bobs in the NHL. Sure, looking solely at players, coaches, and broadcasters named “Bob” is somewhat arbitrary, but it’s led to some interesting corners of hockey history, from before the Original Six era, to the first great shot blocker, to two Hall of Fame players, to one of the most innovative coaches in hockey, to the greatest play-by-play man of all time.

I hope you’ve enjoyed bobbing along this stream of thought with me.