Who is the Canucks’ top prospect? I don’t mean who is he as a player, as that’s yet to be determined, and I don’t mean it existentially, because that’s a huge philosophical can of worms. I mean, quite literally, what is his name?

In Cyrillic, his name is Василий Александрович Подколзин. In the Latin script of the English language, his middle and last name get transliterated as Alexandrovich Podkolzin.

Simple enough. It’s when you get to his first name that things get squirrely.

Sometimes Василий, which is the Slavic form of the name “Basil,” gets transliterated as “Vasili.” Other times, it’s “Vasily.” Just to further confuse things, you’ll occasionally see “Vasiliy Podkolzin” with both the “i” and the “y” at the end of his name, particularly on Russian sites.

So, what’s the deal? Which transliteration of his name is correct? I reached out to Dr. Veta Chitnev, the Russian Language Coordinator at the Department of Central, Eastern, and Northern European Studies at UBC to get the scoop, only to find out that all three are valid.

“There are three possible transliterations of the name Vasily: Vasily, Vasilii, Vasiliy,” said Dr. Chitnev, inadvertently adding a fourth option to the mix with two i’s at the end.

She also noted that the temptation to pronounce his name as rhyming with “silly” is incorrect. “In Russian, it is pronounced as VASEELEY,” she wrote in an email. The emphasis is on the second syllable with a long /ē/ sound, which is never spelled with an “i” in English, just to make things extra confusing.

Dr. Chitnev did say that most famous Russians with that name go by “Vasily” outside of Russia and it appears that’s the case for Podkolzin as well. As much as different writers and publications have used multiple different spellings, Podkolzin’s own Instagram account provides clarity: he spells it “Vasily Podkolzin.”

"Vasily" Podkolzin's Instagram bio.

"Vasily" Podkolzin's Instagram bio.The spelling of his name is among the least of Podkolzin’s concerns, of course. Currently, he’s attempting to play his KHL season in the midst of a pandemic, even among outbreaks of COVID-19 on his own team.

Despite cases continuing to rise in Russia, they’ve eschewed a full lockdown to the pandemic, choosing to instead enforce restrictions with heavy fines. In late October, they reinstated a nationwide mask mandate in hopes of curtailing the spread of the disease.

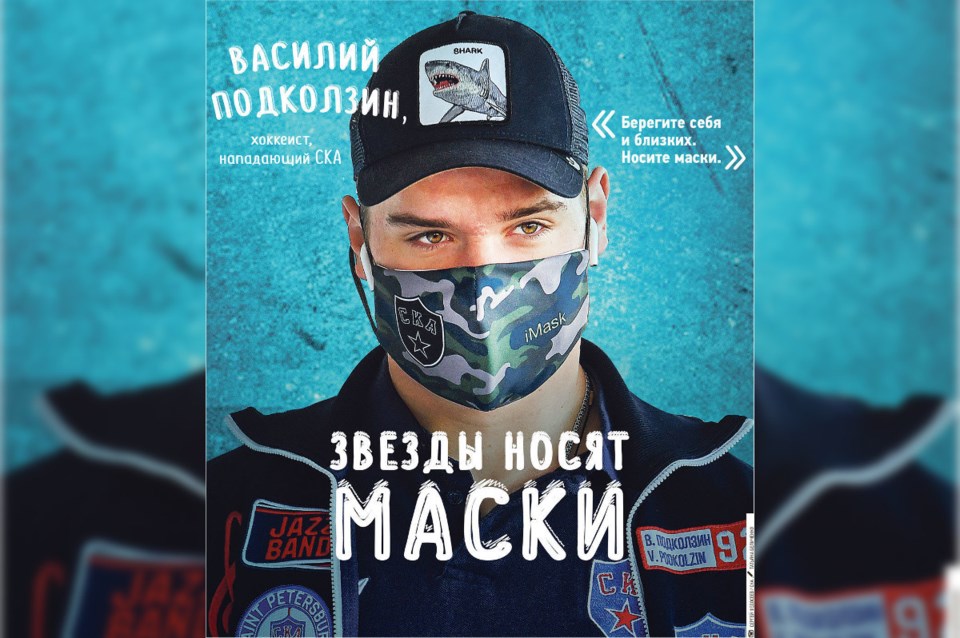

Evidently, not everyone is following the mask mandate, and Podkolzin himself has been called upon to help. Podkolzin is taking part in a “Stars Wear Masks” campaign, urging people in St. Petersburg, where he plays for SKA, to follow COVID-19 safety rules and wear a mask in public places.

“Take care of yourself and your loved ones. Wear masks,” says Podkolzin on the poster.

Podkolzin will face further challenges when he comes to Vancouver after his KHL contract expires. The big winger spoke minimal English when he was drafted, speaking instead through Canucks scout Sergei Chibisov as a translator.

Since then, Canucks GM Jim Benning says that Podkolzin has been working on his English and that “he speaks really good English now.” Still, it can be a tougher transition for a Russian player than for players from some other countries.

“A Russian native speaker faces a lot of challenges, similar to those that English speakers face when they learn Russian,” said Dr. Chitnev. “These two languages are too different in terms of their structure, pronunciation, etc.”

She shared some thoughts from a recent lecture she gave on the subject:

“Although people in the Russian Federation study at least one foreign language at school as a compulsory subject, their level of foreign language proficiency tends to be low. For example, according to data collected by EF Education First in 2016, Russian citizens ranked 34th out of 72 countries by their English language skills.

Among possible reasons for the low proficiency in foreign languages may be the significant differences of the Russian language with non-Slavic European languages. Considerable divergences in grammar and morphology make Western European languages more difficult to learn for Russian people compared to those whose mother tongue belongs to the same language group. For example, English is much easier for German, Swedish or Norwegian people than for those whose first language is Bulgarian, Polish or Russian.

Finally, Russia is the largest country in the world with a robust domestic economy, which makes the need for foreign languages less than in European countries. Also, Russian is the most spoken language in the Russian Federation, and it became the main language of communication between different ethnic groups.”

Fortunately, it does sound like Podkolzin is making good progress with his English. Some Russian players come across to North America knowing little to no English, such as Artem Anisimov when he first arrived to play for the Hartford Wolf Pack in the AHL.

“Zero. I spoke zero English,” said Anisimov to ESPN back in 2017. He had one teammate who spoke Russian, but he left for the KHL after a few weeks, leaving him to pick up English while listening in on his teammates’ conversations.

The toughest part wasn’t on the ice, but the basic day-to-day needs.

“The living stuff was hard to learn,” he said. “Like finding good food, finding good restaurants, gas stations, how to pump your car, all little things you have to do every day. The hockey stuff was easier. You only need to know certain words: ‘Heads up. Time. Chip. Over.’”

The on-the-ice aspect should certainly be easier for Podkolzin, though it hasn’t been a breeze in the KHL either. A lack of ice time and opportunity through most of the season hasn’t helped and he has just 6 points in 24 games. He’s been better in international competition and will have a big chance to prove himself against his peers as captain of Team Russia at the World Junior Championships.

He’ll get plenty of opportunities to pick up the on-ice chatter in English from Team Canada and Team USA, as it shouldn’t be too hard.

As new Canucks goaltender Braden Holtby put it a few years ago, “We're not Ernest Hemingway out there. We're like cavemen, really, with one-word answers. We're really dumbing things down here.”

Of course, Hemingway was famous for his economical and to-the-point prose, so perhaps hockey players aren't far off.

On the ice, it can even be an advantage to have another language or two in your back pocket. Daniel and Henrik Sedin would regularly set up plays before a faceoff in Swedish, particularly if they were on the ice with fellow Swedes like Alex Edler, Mattias Ohlund, or Mikael Samuelsson. If Podkolzin gets a chance to play with another Russian in Vancouver, such as fellow Canucks prospect Dmitri Zlodeyev, that could come in handy.

The biggest challenge will likely be talking to the media, where expressing yourself with nuance in a second language can be difficult.

Consider Seattle Mariners legend Ichiro Suzuki, who famously used a translator for interviews throughout his career, despite being fluent in English. He even learned some Spanish — mostly cussing — so he could trash talk Latin players while on the basepaths.

“We have to connect to our fans through the media, and when you talk about that, it's got to come from your heart,” said Ichiro once, of course through his translator. “And when it comes from your heart, it has to be absolutely consistent. There’s a big risk you take without an interpreter because as professional baseball players, we are here to perform baseball, not to learn a language.”

For Ichiro, it was far easier to express his true thoughts in his native language, which makes perfect sense. The answers Podkolzin could give to a question in his native Russian would be far closer to his true thoughts than answers that same question in English.

It can take years to become fully comfortable with another language, to the point that you don’t just understand and speak the language, but actually can think in that language without that moment of translation in your head. Sometimes, that moment never comes, particularly if you’re not immersed in a culture that uses that language.

Even the Canucks last Russian star, Pavel Bure, who has since said he learned English when he was younger from watching Full House, conducted his early interviews through an interpreter.

Of course, Podkolzin could surprise us all and speak fluent English by the time he arrives in Vancouver. But even if he doesn’t, at least the media will know how to spell his name: “Vasily Alexandrovich Podkolzin.”