Sex workers in particular — with their precarious legal status and de facto criminalization — did not seem to be accounted for in any of the programs.

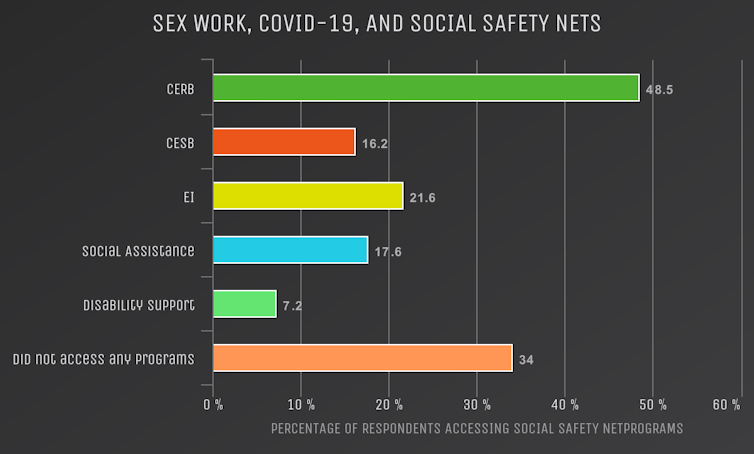

Many progressive organizations and scholars pointed out that sex workers would likely be excluded from new programs like the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) and the revamped Employment Insurance (EI) scheme.

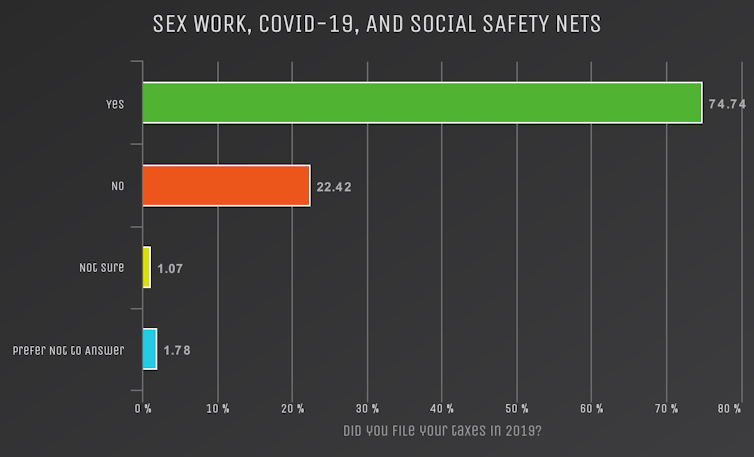

Both required claimants to have filed income tax in 2019 citing at least $5,000 worth of income. Due to the perception that sex workers don’t file income taxes because of stigma and fear, sex worker-led emergency mutual aid funds were created across Canada.

As members of organizations implementing these kinds of emergency economic supports for sex workers ourselves, we saw firsthand the impact COVID-19 had on their economic security. However, as time passed and income replacement programs continued to evolve, we began to question the presumption that sex workers were not accessing these programs.

The working conditions study

In collaboration with Prostitutes of Ottawa-Gatineau Work, Educate, Resist (POWER) we secured a small grant to survey sex workers in the national capital region. We created a short bilingual survey asking sex workers about their working conditions during COVID-19, their ability to access social safety net programs (new and old) and their tax-filing habits.

We launched the survey in June 2021 and received 304 completed surveys over six weeks.

A full detailed report on our findings is forthcoming, but we wanted to share some of our preliminary results as they are timely and should inform future policy. As sex workers fighting to decriminalize the industry are due back before the Supreme Court at any moment and social safety net programs continue to evolve, this information needs to be shared.

Sex workers & taxes

There is a lot of speculation about whether or not sex workers file income taxes — reasons cited are often fear of criminalization or stigma associated with working in the industry. And unfortunately, data on sex workers’ tax filing habits is difficult to find.

Many researchers focus on sex workers’ sexual health and physical safety, while others conflate sex work with trafficking. A quick look at POWER’s own research repository illustrates this. Thankfully, there is a growing body of research on the working conditions of sex workers in Canada to which our study contributes.

Like workers in other sectors, sex workers are a heterogeneous group. Some work full-time, others part-time, or casually as gig workers. Some even operate as small business owners while others work for third parties.

Sex work was the primary source of income for 76.6 per cent of our survey respondents, with 16.3 per cent noting that sex work was supplementary income and seven per cent reporting sex work as an occasional form of gig work.

The majority of sex workers in our study said they file their income tax regularly and it is a routine part of their business practices. Some workers note that claiming income has enabled them to access other income-related resources, including social safety net programs like social assistance and mortgage agreements.

For less than 25 per cent of sex workers in this study, claiming income from sex work remains challenging. They said taxes invoke worry, fear and anxiety as many are concerned about the repercussions of filing income associated with legal and illegal activities.

Sex workers & CERB

Prior to the pandemic, 41 per cent of survey respondents reported accessing social safety net programs (like EI or disability) at some point in the past. This indicates that a significant number of sex workers have successfully navigated social safety net programs at the federal and provincial levels.

While almost half of our respondents (48.5 per cent) accessed CERB at some point in the first year of the pandemic, an additional 54.5 per cent experienced a period of not having any financial support. Overall, just under a quarter of respondents (23 per cent) indicated they never stopped working despite the risk.

What happens next

This research shows how diverse sex workers are and how we cannot talk about them as a monolithic group. Working within a sector of the economy that is stigmatized and criminalized takes skills, savvy and nerve. How sex workers have navigated both the pandemic and relief efforts in the Ottawa-Gatineau region shows this.

As the pandemic wears on, many more sex workers will continue to access social safety nets. These workers know their rights, and they demand inclusion in future policy.

Ryan Conrad received funding from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council's Partnership Engage Grant COVID-19 Special Initiative to conduct this research in collaboration with Prostitutes of Ottawa-Gatineau Work, Educate, Resist (POWER).

Emma McKenna received funding from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council's Partnership Engage Grant COVID-19 Special Initiative to conduct this research in collaboration with Prostitutes of Ottawa-Gatineau Work, Educate, Resist (POWER).