One of the more familiar Christmas songs, “It’s The Most Wonderful Time Of The Year,” has a line that to me always seemed out of place.

Popularized by Andy Williams in 1963, the lyrics portend: “There’ll be scary ghost stories / And tales of the glories of / Christmases long, long ago.”

Ghost stories at Christmas? Who does that?

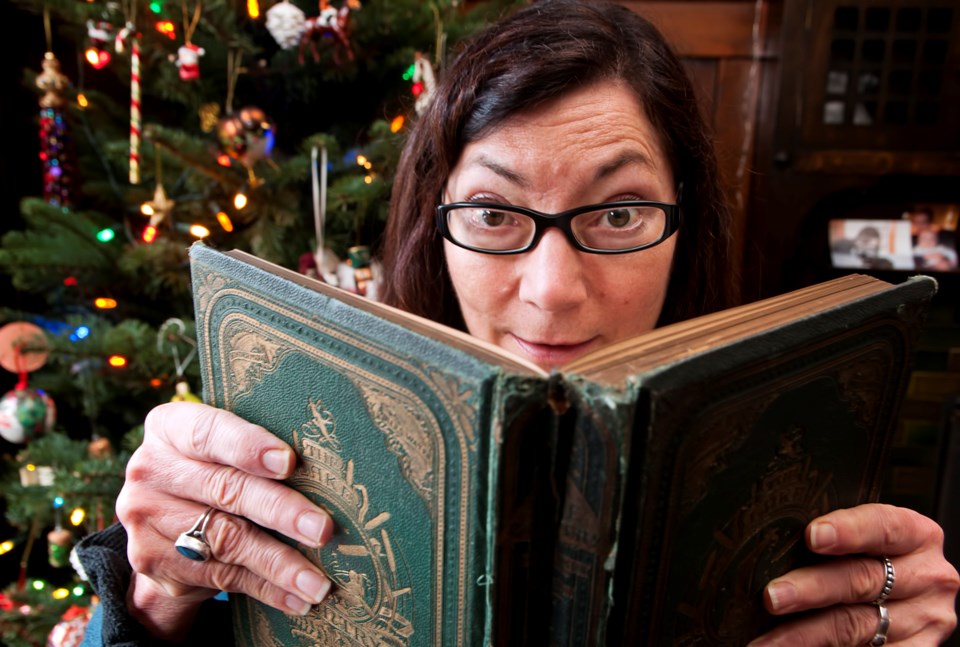

It turns out you don’t have to look that far to discover that Christmas and ghost stories have a long history. The most obvious example had to be pointed out to me. One of the most beloved cinematic traditions of the season is Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol.

We don’t really think of this as a ghost story, maybe, because the ghosts are basically doing old Scrooge a favour. When we think of the book or the film, it is about the redemptive story of a misanthrope who turns himself around during the holiday season, not so much about our conventional ideas of what a ghost story looks like.

Beyond this example, which had been staring me in the face, there is apparently a very long, albeit largely unchronicled history of telling scary stories around Christmas. Margaret Linley, a professor of English at Simon Fraser University, says folk traditions frequently involved telling spine-tingling tales. In Scandinavia, for example, this would begin in early December and culminate around Yuletide.

No one can say for sure when this began, but it probably has to do with long, dark evenings and nights in the pre-TV age. There was little to do to pass the time and, while you might think keeping the tots from being terrorized would be a priority, there has always been that alternative parenting approach, in which fear is a handy motivator. Early fairy tales provide harrowing examples of this. So do some sacred texts.

Linley says the Dickens’ gem illustrates a great deal about the time it was written and that, in turn, has influenced a great deal about how we think of Christmas. For one thing, remember, many people in Dickens’ time accepted the idea that ghosts or spirits wandered the earth.

Many cultures believed that times like the winter solstice were when the sheath between the spirit world and the material world was thinnest. The Victorian era was also a time, Linley says, when spiritualism was at a peak. This is the belief that spirits want to communicate with us mortals, through such mechanisms as mediums, séances and Ouija boards.

Ghosts, or spirits, were not viewed as necessarily menacing. If they were departed loved ones, they would obviously be welcome visitors. Even if they weren’t familiar, Linley says, spirits in the Victorian era were frequently associated with generosity and portents of good things.

In many cases, they would have been more Casper than Blair Witch.

Dickens and some of his contemporaries were also conjuring nostalgia for Christmases past. Successive waves of puritans, religious fundamentalists and general buzzkills had attempted to strip Christmas (and everything else) of frivolity.

Dickens’ Scrooge may have been the very embodiment of that humbug attitude and a series of spectral nocturnal visitors was just the thing to scare him back onto the path of kicking up his heels on Christmas.

We may feel superior to ancestors who believed in ghosts, but there are plenty of people today who look down on all supernatural beliefs, including the idea that the son of God was born this day.

So consider the fact that when Dickens was writing, not only was the idea of ghosts widely accepted, there were no Sam Harrises or Richard Dawkinses to tell people that their core religious beliefs were hooey.

“There is just a traditional belief in the supernatural,” says Linley.

Christmas is a perfect time for intermingling ideas of Jesus, the holy ghost, the kinds of spirits that were believed to hover in the dark and any number of associated or unrelated ideas. The supernatural, by definition, invites the mingling of the unknowable and the unprovable.

Despite the certitude of many Christians, we live in a time when plenty of people do not believe in the story of Christmas. Yet many will also suspend disbelief for a time, hoping that good things will come at this time of year just because of a spirit of human goodness or something in the air.

Although they may not believe in ghosts, as such, a few people on my Facebook feed have recently mentioned feeling the presence of lost parents and friends particularly at this time of year.

“It’s a period of wonderment,” says Linley. “Christmas is a time of miracles, things that you can’t explain and, along with that is the miracle of the birth of Christ. There is also this belief that other spirits may be trying to get in contact with us.”

Whatever you believe, may the spirit of Christmas visit you.

[email protected]

@Pat604Johnson