An event last week in Vancouver marked the life of one of the most charismatic and influential Jewish leaders in history.

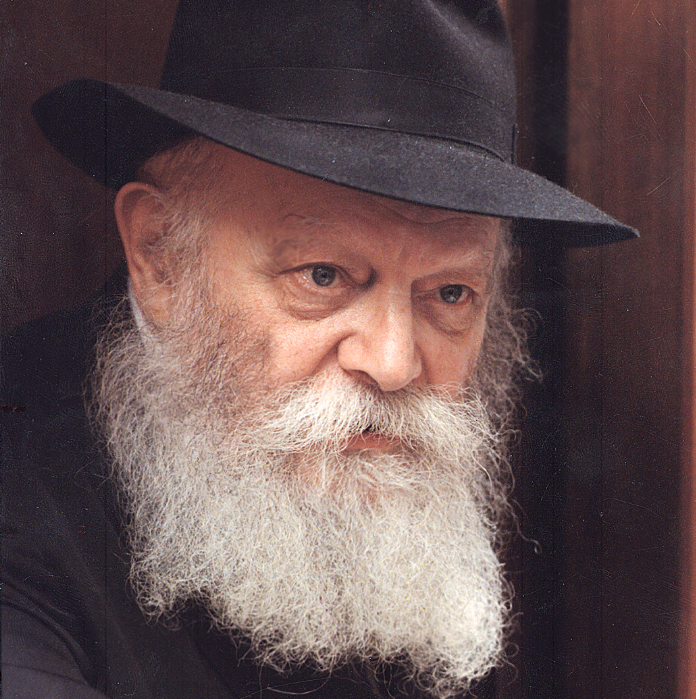

The Rebbe, as he was (and is) known, had an impact on Jewish life that was “unique not only in our generation, but throughout Jewish history,” Rabbi Binyomin Bitton told the crowd. To understand the impact of the man is to understand something of the catastrophe and revival of Jewish life in the past century.

Lubavitch is part of the Hasidic movement. Hasidism, which means piety, emerged among Jews in eastern Europe in the 18th century. It places an emphasis on Jewish mysticism, called kabbalah. (A watered down version of this complex theology has been popular among celebrities like Madonna.)

Judaism is very much centred around study of Torah and Talmud — the Hebrew Bible and its encyclopedic commentaries compiled by rabbis across centuries. Hasidism added to that devotional learning an emphasis on the physical and the emotional, with much dancing and singing, some of it ecstatic.

Streams of Hasidism tend to be closely associated with the towns of their origin. So Bobovers originated in Bobowa (now in Poland), Satmars in Satu Mare (now in Romania) and Lubavitch, with a town now in Russia. Dozens of other “dynasties,” some tiny, comprise Hasidism. The term Lubavitch is interchangeable with “Chabad,” the philosophy that emerged there and an acronym for the Hebrew words wisdom, understanding and knowledge.

Before coming to lead Lubavitch, Menachem Mendel Schneerson escaped Europe in 1941, as Hitler’s Final Solution was nearing implementation. In 1933, Europe had a Jewish population of about 9.3 million.

Six million were killed by the Nazis and their collaborators. Among the most devastated Jewish communities were those where Hasidism was strongest, like Poland, which had three million Jews in 1939, and where just 45,000 survived.

The small number of Hasidim (as they are called) who escaped before the war and the even smaller number alive in Europe in 1945 faced a world of annihilation. Their civilization, including the Yiddish language, was almost entirely destroyed.

From places like Jerusalem and Crown Heights, Brooklyn, the “surviving remnant” sought to rebuild the world of ideas and tradition that had been lost. The Hasidic groups that succeeded have done so largely through extraordinarily high birth rates. Lubavitchers took that approach too, but under the Rebbe, they took another approach as well, which proved stunningly successful.

Rabbi Yitzchak Wineberg leads Chabad Lubavitch B.C., the headquarters for the eight centres in the province and is Vancouver’s longest-serving rabbi. He says the Rebbe turned Lubavitch “outward.”

When the Rebbe assumed the leadership of Lubavitch in 1951, after the death of his father-in-law, the previous Lubavitcher Rebbe, the movement began to reach out to the growing number of Jews in Israel, North America and elsewhere who had fallen away from Jewish observance.

To encourage non-religious Jews to find relevance and rededicate themselves to their tradition, in the past half-century Lubavitch has set up outposts — Chabad Houses — in the most unlikely places.

After their mandatory military service, huge numbers of largely secular young Israelis head to India, Nepal, Southeast Asia or elsewhere for weeks or months of R&R. There, in Himalayan villages, the marketplaces of Bangkok or the hippie haven of Venice Beach, Calif., they find a star of David, familiar food and people who speak their language. Some of them have an evening of home-like camaraderie far from home. Others have life-changing epiphanies.

Jews from all over the world, even if not particularly religious, will often seek out a Chabad House when travelling during important Jewish holidays. With 3,300 Chabad organizations worldwide, they often do not have to look far.

Vancouver is not quite the Jewish desert of, say, Kinshasa, but you can find Chabad in East Van, downtown, UBC and five other places in the province.

This extraordinary visibility is the most evident legacy of the Rebbe, and the reason Lubavitch is now the largest Hasidic group.

This may be the most evident result of the Rebbe’s outward turn, but spiritual impact has been so vast that there are some among his followers who have suggested the Rebbe was (or is) the long-awaited Jewish messiah, a contention that has understandably resulted in intense controversy among Jews within the movement and beyond.

Those who pass out photos of the Rebbe with the Hebrew word for Messiah (mostly in New York and Israel) are rare and considered fringe-y. Even so, perhaps in typically Jewish style, on the one hand, ambiguity reigns and, on the other hand, uncertainty.

Mainstream Lubavitchers do not say the Rebbe is the messiah, but neither do they say he’s not. In every generation, tradition says, a figure with the potential to redeem the world walks among us.

Time will tell if Schneerson is the Jewish messiah. But for the last 20 years, Lubavitch has not replaced him as their leader, being officially without a dynastic leader for the first time in more than 200 years.

Meanwhile, it has experienced record growth in numbers.