In the Feb. 4, 2011 edition of the Vancouver Courier, contributor Aaron Chapman wrote a feature story on the history of gangs in Vancouver, including the so-called “park gangs” of the 1960s and ’70s. It would inspire his latest book, The Last Gang: The Epic Story of the Vancouver Police vs. the Clark Park Gang, which will be released next week by Arsenal Pulp Press. Here is an exclusive excerpt from the book. A warning to readers: the following includes coarse language and profanity.

It was June of 1972, around the same time that a team of burglars was arrested in a botched robbery at the Watergate Hotel in Washington, D.C., and a few days after the Rolling Stones concert. In Clark Park on a warm summer night, Gerry Gavin, Roger Daggitt, Albert Hill, and a kid named Phil Benson (name changed) were all drinking beer near the top of the pathway nearest to Commercial Drive. The park was empty at that hour. It was a quiet weekday night, the silence broken only by the sound of the occasional vehicle driving along Commercial. The gang joked and drank and passed around a joint. Benson, more of a hanger-on than a real member of the gang, had brought a small battery-operated radio, and its tinny speaker played music from a local rock station.

• • •

In a break in the conversation, Hill walked away from the others to urinate behind one of the nearby trees. As he zipped up his jeans, he turned around and saw a man in the dark standing several feet away, staring at him. “Jesus Christ — what are you doing?” Hill asked. “You watching me piss or something?!”

The man said nothing and continued to stare at Hill. The others, overhearing their friend’s alarm, quickly walked over to see what was happening. The man stood partly in silhouette, lit unevenly by the street lamps off the Drive, which shone into the park through breaks in the tall trees. He was wearing cowboy boots and a corduroy jacket.

“What’s your fucking problem, man?” Hill demanded.

The man in the dark moved slowly a few feet forward, stepping more into the light. He appeared older than them, perhaps in his late 20s or early 30s, and had a medium build. Benson turned off the radio he was holding, suddenly dropping the standoff into silence.

“We’ve met before,” the man said casually. Hill looked around to see who he was looking at, but he seemed to be looking at all of them.

“Who the fuck are you? I don’t know you, man,” Hill said, now more angry than alarmed. “What the hell are you doing here? Get lost.”

Benson thought he might be a Riley Parker, or because of the man’s cowboy boots, one of the guys from the Out to Lunch Bunch he’d heard about. Maybe he was from some other street gang, looking for a fight. As Gavin and Daggitt stepped forward with fists clenched, three other men stepped forward from the darkness behind them. In a brief scuffle, they violently grabbed Daggitt and Gavin, locking their arms behind their backs. Another man darted out of the trees and grabbed Hill, twisting his arms back the same way. Benson saw that they were all about the same age as the first man, but noticeably bigger, and wearing jeans and boots. One had an old army jacket on and the other an old T-shirt. Roger Daggitt, then only 18, was already large and strong, and it took two of the men to hold his arms back. Benson began to panic and wondered how long the men had been there watching them.

Now, caught in the middle, he felt like he ought to run, but suddenly he felt a firm hand on his shoulder that jolted and froze him at the same time. It was the first man whom Hill had encountered in the darkness, but Benson was too scared to look him directly in the face. Instead, Benson looked off to see that Gavin, who had initially put up a struggle, had also given up more quickly than Daggitt had. That’s when Benson noticed that Gavin had a revolver jabbed into the side of his ribs; the light from the street lamps reflected off the gun metal.

“I was going to tell you to get lost, kid,” the man said to Benson. “But now I think you should stay and hear this.” Addressing the group in a measured voice, he said: “You guys have to stay out of the park now. This is our park. You understand? It’s over. Day or night. I don’t fucking care. You’re not hanging around here anymore. You got it?”

Daggitt, Gavin, and Hill said nothing, and Benson was too scared even to move. He then noticed that there was another man who must have been keeping an eye on the front entrance of the park in case someone unexpectedly walked up the path. He now came up to join them, but stayed back a distance and kept quiet.

A few silent moments passed. “Just so you understand... Our gang is bigger than your gang. That’s it,” the man said, then turned to walk down the hill.

Hill was let go first, then was punched in the stomach by the man who had held him, and he fell forward. Then Daggitt was shoved away by the two men holding him. Gavin was let go last, but not before being backhanded in the head. Gavin swore and stepped forward as all of the men now walked away. One of them muttered, “Don’t fucking be here again tomorrow night,” then disappeared into the darkness of the park.

Benson, more confused and nervous than the others, watched as Hill stood up, getting his wind back. Gavin rubbed his head and swore. And while Benson didn’t know Roger well, he looked angrier than Benson had ever seen him and made a motion to go after the men, but Gavin put out an arm to hold him back.

No one said anything for a few moments until Benson broke the silence, nervously at first and then more insistently. “What the fuck, man? Since when did the Riley Parkers pull shit like that or bring guns with them? Right into Clark Park? What the fuck, man? Let’s go get them!

They’re probably still down on Commercial!”

“Shut up, Phil,” Gerry Gavin said, cutting him off. “That wasn’t the Riley Parkers. That was the cops.”

• • •

The VPD’s H-Squad remains one the more guarded secrets in the history of the Vancouver Police Department. Little information was recorded or filed about its mandate. The poor filing techniques and an absence of digital records makes material from the early 1970s difficult to find in the VPD archive; only major crimes such as unsolved homicides are retained from that era. In 2016, I filed a Freedom of Information request to the VPD to see what I could uncover, but no surviving records or reports from the H-Squad can even verify its existence. The only time any H-Squad member has spoken publicly about their posting is when a couple of surviving members of the H-Squad agreed to be interviewed for this book.

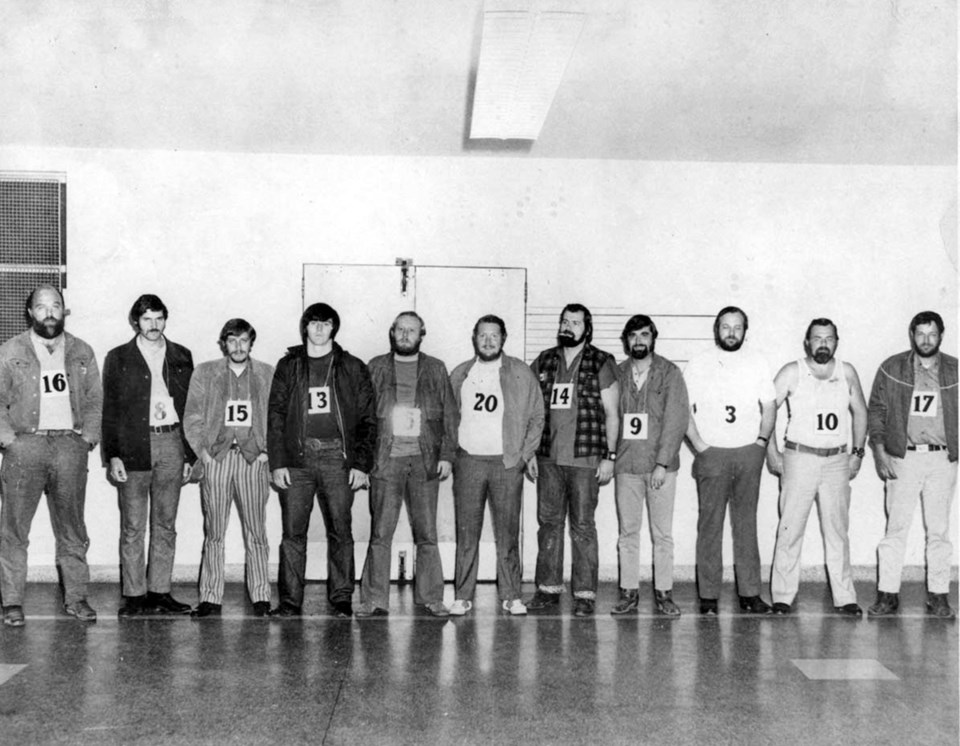

Curiously, the one record from the Heavy Squad can be found in the public records of the Vancouver Police Museum. It is a photo of the 11-member plainclothes squad in a mock police lineup.

Many of the officers are smiling or laughing for the camera, giving the impression that the photo was taken for their own amusement, not for official records. How this photo of the squad ended up in the Museum’s collection is unknown.

• • •

The Clark Parkers do not remember them fondly. “They’d show up and just say, ‘OK, who are we taking in tonight?’” recalls Gary Blackburn. “But a lot of us back then could slip out of a pair of handcuffs. You’d flex your wrists as they put them on, and then relax them once you had them on. But then they started putting handcuffs on so tight that they’d cut into your skin, or else use two pairs at once.”

Blackburn and the others were used to cops arresting or questioning them in the park, but noticed that the attitude of police changed after the Rolling Stones riot. One evening, the squad raced into the park in their ghost cars, slamming on their brakes in front of the gang. “They were like bikers,” says Mac Ryan. “They almost ran us over! We knew they were cops, but not at first, when they showed up like that. I had some weed on me, and I didn’t feel like going to jail, so I ran around to the back of the field house. The weed was in a cigarette pack, and I threw it on the roof. When I walked back, one [squad member] grabbed me and hit me in the gut.” Tossed into one of the ghost cars, Ryan was driven down to the waterfront. “They threatened me that they could do this and that or just kill me and dump my body somewhere and it would never be found.”

• • •

Many surviving Clark Parkers who recall this period insist that they were given overly hostile treatment, especially when initially the squad’s scare tactics didn’t persuade them to quit hanging around the park... Clark Parker John Twynstra encountered the H-Squad one night and received a beating that kept him recuperating at home for a week.

From this sudden change in tone of policing around the park, rumours began to spread that off-duty police officers had formed a vigilante squad to go after the Clark Parkers. It was difficult for some to fathom that such a squad was officially sanctioned. Allegations of police abuse raised by Clark Park gang members are not to be wholly disbelieved. [Police officer]Paul Stanton [name changed] candidly admits, “I don’t remember [picking up suspects and kicking them out of squad cars far from the park] personally. But I do know it was done in general back then. That sort of thing wouldn’t have been uncommon for the time. If you had a problem and you couldn’t do anything about it, you’d pick them up and drop them off in one end of town and let them walk back. That certainly isn’t done anymore. But, obviously, the whole squad itself isn’t the kind of thing that would or could be done anymore.”

• • •

By July 1972, the heat from police was so great that the gang refrained from hanging out at the park. Members either gathered at individual homes or, now that many were of legal age, at bars like the Biltmore Hotel, the Eldorado, Lasseter’s Den, the Blue Boy Hotel pub, or the Vanport Hotel. As a result, the H-Squad began to harangue individual Clark Parkers on the street.

“They always wanted to know who ‘the leader’ was,” Blackburn says. “That was always the biggest fucking joke — there was no leader. We never had one. The scene was, if you wanted to do something, you just went ahead and did it. There weren’t any rules or some code to go do this or that. We were ‘organized’ to the extent that we stuck up for each other, and if you tried to fuck with one of us, you were going to fuck with everybody.”

“The H-Squad knew where everybody lived. You couldn’t go anywhere after a while,” remembers Mac Ryan who, even at the worst of times, dealt with the squad irreverently. “They’d come into the nightclubs that we’d started to go to and stop and question me. I’d say, ‘I’m the leader on Tuesday. No, wait a minute, I’m on Thursday, somebody else is tonight, and another guy is tomorrow.’ I’d tell them the leader’s name was ‘Jack,’ and when then the cops would ask what his last name is, I’d say ‘Me-off.’” Ryan’s impudence inevitably earned him another rough midnight ride in the back of an H-Squad car.

However aggressive the squad’s tactics might have been, their success was also quickly noted by many who lived around the park who had seen their neighbourhood decline. Retired constable Vern Campbell remembers, “An old lady who lived across from Clark Park was talking to a uniformed officer one day and he asked her how things were going in the park. She said things were much better since the ‘older’ gang arrived!”

While the Clark Parkers might have temporarily abandoned the park, the H-Squad also seemed to embitter the hangers-on and others who were on the gang’s side or who were merely anti-police. It was believed that the police had gone above the law to get rid of the gang.

“They couldn’t beat us fairly. So they had to invent a goon squad to try to put pressure on us. That didn’t stop us. It just made everybody more pissed off,” says Mouse Williamson, who thought the tactics of the squad upset what he and others in the East End regarded as the code of the streets. “It’s like cops and robbers; if you get caught fair and square — that’s the way it goes. We’re supposed to be the liars, cheaters, and schemers, not those guys. They’re supposed to be honest, and do things by the book, but they threw the fucking book away on us.”