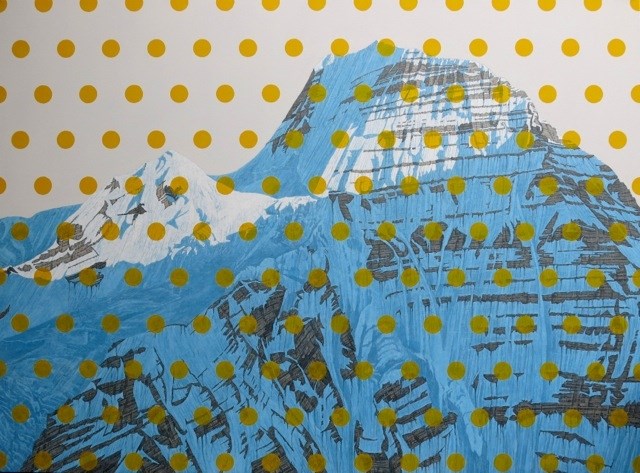

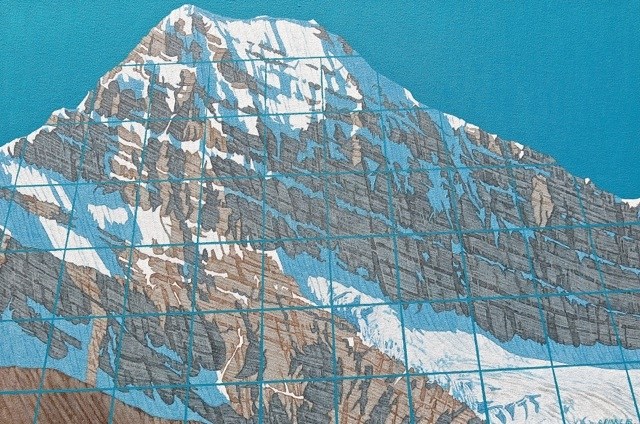

When David Pirrie sees a mountain he loves, the North Shore landscape painter quietly lifts it out of its surroundings and transfers it – crags, crevices, ridges and all – cleanly onto his canvas. But instead of stopping there, after each shadow, gully, and snowy crest has been painstakingly realized in monochromatic detail, Pirrie does the unthinkable: he vandalizes his own landscapes, marking their surfaces with his instantly recognizable signature of pop-art dots and lines.

In advance of Mapping the Rockies, his upcoming exhibition of all-new works at the Ian Tan Gallery on South Granville, we caught up with the avid mountaineer to learn more about his process, and the mountains he loves most.

KK: Do you ever pause, after painting a stunning mountain face, and question adding the dots or lines?

DP: I start my paintings with a pretty clear path to completion. The colour I end up using for the background and overlays gets dictated only later, as my choices are grounded in colour theory. Once I am close to finishing the landscape part of the painting, I then proceed to counter the monochromatic palette of the mountain with intense pantone based colours as a background, which also usually leads into a dot matrix or map grid overlay on top of the mountain.

This aspect of my work is both conceptually and formally driven. Formal in the sense that it is derived from colour theory and employed to effect the overall composition, meaning the colour becomes an integral part of the painting.

Has adding these dots and grids changed how you are perceived and received in the art world? Had you experimented with “plain” landscapes before moving in this direction?

My very first series of mountainscapes were very small minimalist cutouts of mountains with no overlays and a stark white back ground. In 2004, I completed a new series titled Subduction Zone, where again the mountains were excised from their surroundings, but I added rectangular grids to convey movement. These series were very well received and gained quite a bit of attention.

My first series with dots was a body of work titled Codified Topographies. These works were still on a grey monochromatic background but I added a grid of semi transparent dots over the landscapes. It was one of those viola moments for me, propelling the paintings into a more engaged contemporary dialogue. Subsequently my work started to gain broader appeal and I became more ambitious with my use of colour.

Do you embrace the pop-art label? Or think of your work in a different context?

I have struggled for some time now as to how to talk about my work in the larger scheme of the art world. Definition is important for many as it helps place an artwork or idea in a clear lineage of accepted art terms. The pop-art reference to my work is understandable, however I do not ascribe to this line of thinking. What

I need is a new word to describe my work. It’s landscape but not, it has conceptual and formal grounding but uses really poppy colours, it’s a little science with all the grids and study of geography, it’s very graphic and hard-edged. I could go on…

What is your process – do you paint from photographs, memory, or imagination?

To get at the basics of what I am doing now I start with the subject. It may be a mountain I have climbed or skied, or perhaps in the vicinity. All my work is based on photographs, which I project onto a hand-stretched canvas. The image is considered compositionally before executing the initial drawing. All of the prominent features, darks and lights, snow etc. are then drawn out in detail.

I employ a pretty classic approach to painting, starting with a sienna-like colour ground. I then start blocking in my colours with layers of glazes, using paint thinner to move and remove paint, sometimes heavier to let the paint run. This is followed by a slow building up of tinted glazes, with an effort to let as much of the light pass through.

Once I am close to finishing the landscape part of the painting I then proceed to counter the monochromatic palette of the mountain with intense pantone-based colours as a background, which also usually leads into a dot matrix or map grid overlay on top of the mountain.

Why mountains? Where does the interest come from?

I am deeply immersed in mountain culture. I’ve spent my life exploring the mountains on foot, skis and mountain bikes. Growing up in North Vancouver, I would ask the adults what was on the other side of the North Shore mountains and they could never tell me, so I had to find out myself. It was only much later in my artistic path that I began to investigate the mountain. Once I combined all my interests in cartography, architecture and the mountain I had a voila moment.

Describe the new collection. What sets it apart from your previous investigations?

This new body of work is all about the Canadian Rockies. I have spent many a climbing and ski touring/mountaineering trip to this vast area and have always come away with a special understanding of geological time. The stratification in evidence, the layering of hundreds of millions of years of sediment cannot go unnoticed, and I developed a special relationship with its complexities. I was also reminded of the importance of Canadian landscape imaging with the recent major show of Tom Thomson’s work at the LA Hammer. Featuring his iconic paintings of mountains mainly from his sojourns to the Rockies, it was curated by Steve Martin and brought fresh light to an important intersection of Canadian landscape painting.

Three lines of investigation form the basis of this show. Exploded contour maps of the ice fields I would use to navigate the complex mountain environment, portraits of mountains I have skied or climbed with longitude and latitude grid overlays extending the concept of relief and travel, and dot overlays on mountains as a form of plotting. Still perhaps in an experimental stage, the Map paintings take on an almost abstract quality, while retaining my rigorousness for details.

What are some of your favourite mountains to climb around the world?

When I am ski-mountaineering and there is three feet of fresh powder, that is my favorite mountain! Kidding aside the Waddington Range of the BC Coast Range is in the top of the list. The Tombstone Range in the Yukon and the Grand Tetons in Wyoming are up there also.

Do different mountains speak to you differently, have different personalities? What stories do they tell you and how?

This all comes down to the fundamentals of geology, plate tectonics and erosion. Each chain of mountains tells a story of uplift and erosion. Sedimentation, stratification and rock formation are vastly different form one region to the next. The Coast range is young metamorphic granite while the Rockies top layers of sedimentation have ocean fossils embedded in them.

So yes each mountain I paint tells a story, how a glacier carved out its peak 10,000 years ago for example. On a personal level each peak I paint takes me back there, navigating its complexities.

How long have you been painting these landscapes and what have you learned about mountains in this time?

I have been painting mountains for roughly 10 years now and in that time I have developed an intuitive understanding of the morphology of mountains – their folds, cirques, arêtes and glacial systems. I have also come to understand that the mountain is universal in its attraction as a trope for the sublime and the unattainable.

Have the mountains you paint and frequent changed at all over the course of your career, environmentally speaking?

The loss and recession of western Canada’s ice fields and glaciers cannot go unnoticed. This, in fact, will become a critical point in my work. A recent study published in the Globe and Mail predicts with much certainty a loss of 50 per cent of ice mass in the coast range of BC and a whopping 80-90 per cent in the Canadian Rockies by the end of this century.

As glaciers recede new landscapes emerge, landslides occur as vast amounts of glacial till is left exposed. Rising melt water swells rivers in the late summer, leading to greater flooding. Receding glaciers have drastically changed many of the mountains I visit. In fact, many of the glaciers I used to use as ascent routes in the Garibaldi Park region do not even exist any more.

Why paint them on a blank, skyless background?

In removing the individual mountain from the surrounding range I decontextualize the subject, making it symbolic rather than representational. I treat the mountains like celebrities, fashioning larger than life, unattainable, beautiful and mysterious portrayals.

What is the furthest or most exotic mountain you have been inspired to paint?

As I write this I am completing a large painting of the Torres Del Paine region in southern Patagonia, Chile. This is the first painting I have done where I have not visited, but I soon hope to rectify that.

I’ve read the words plotting, mapping, and travel to describe the intention behind the dots and lines, but I want to know more… Can you elaborate on the meaning behind the colour and the number, or the dots and lines themselves?

Perception is key. How an eye travels across a picture plane has been studied and elaborated on since the first cave painting. With the advent of perspective in painting it became evident the artist can direct the viewer to new ways of understanding our world. When I first employed a dot matrix over my paintings I had a curious discovery that the eye became more focused on the mountain, whilst also vacillating back and forth to the dots. Foreground and background becomes fragmented, leading to a vibration between planes.

Has anything else grabbed you so much? What other subjects do you enjoy painting?

I have begun a series of map paintings, some of which are on view for the show.

These works are exploded contour maps of the ice fields I used to navigate the complex mountain environment. Created out of the same interests as all of my other work, these works still retain a rigorous formal construction while also taking on a very abstract feel. It is with these new series that I hope to start an inquiry into climate change and its effects on our glaciers.

• David Pirrie: Mapping the Rockies runs April 9-30 at the Ian Tan Gallery (2321 Granville). Opening reception April 9 from 2-4pm. IanTanGallery.com