With her debut novel, The Heaviness of Things That Float, author Jennifer Manuel puts herself out on a limb.

Both Manuel and her protagonist, a middle-aged nurse named Bernadette, are white, and yet together they boldly tell a story from the outskirts of a coastal First Nations community that depicts – with remarkable intimacy – the tenuous balance that exists between native and non-native neighbours.

In the novel, Bernadette is packing up to retire and leave the small community she has served for the past 40 years, when a young man she cares for goes missing. In the ensuing community crisis and tense introspection, a question of privilege arises: can an outsider like Bernadette truly belong?

Manuel is an award-winning short story writer and a long-time activist in aboriginal issues, having taught at schools on Tahltan and Nuu-chah-nulth lands and worked in areas as remote as the setting of her novel.

We caught up with the Vancouver Island resident by phone to learn more about the backstory of this tragic yet inspiring tale. Answers have been lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

Who are some contemporary First Nations authors whose writing informed this story?

Ooh, quite a few. Two I can think of off the top of my head would be Eden Robinson, whose book Monkey Beach is set up in Kitimat, and is a really unflinching look at the various struggles that have come out of the legacy of colonialism for First Nations people. The other author that really, I think, tells the most powerful tales of the kinds of things that I was addressing would be Lee Maracle. She’s from the Sto:lo Nation and her books, I find more than anyone else’s, address how much the legacy of colonialism has affected women. For instance, she’s got a book called Daughters are Forever, and that looks specifically at the guilt that some First Nations mothers feel when they’re caught up in a cycle of dysfunction that arises directly from residential schools and the reserve system.

How do you present your characters’ flaws without seeming to pass judgment?

It requires constantly re-evaluating what you’re thinking and why you think it. That’s part of the point of the book – I presented this woman as having been there for 40 years because 40 years is so long, and I could make the point that even somebody who has been there for 40 years will still harbour assumptions. That’s almost a statement about myself, too. Even as I’m writing this book, no matter how much I try to analyze myself, my assumptions will still potentially be in the book. That’s why I wrote it from a first-person perspective, because it’s not this over-arching narrator who’s saying this is the way it is. It’s from her perspective and her perspective is flawed.

What do you think will be the main difference between books written about First Nations culture now, compared to before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission?

To back up a bit... When I looked at old books that had been written in the past by other novelists about First Nations people, I was often appalled. I mean, they're writing from a different time – even 20 years ago – but they appropriated so much. And so I wanted to write a book that wasn’t appropriating their voice, but [rather] giving a non-First Nations voice to their experience, and how flawed the perspective is of the outsiders that go in.

If you imagine, people in this political climate are scared to write about these issues because they don't want to appear as thought they're appropriating anyone's voice. And that's a good thing. But then I don't want to leave this void where [hypothetically] as of 1995 we have no more books where non-First Nations people are talking about these things honestly, right? For a long time, for instance, W.P. Kinsella was known for writing these First Nations characters, which, when you look at them now, they are so stereotyped, and that's sort of what I'm talking about. Because this is all a shared narrative. Our society and the history of First Nations people, some part of it is a shared narrative in terms of what's gone on, so we do need to have a dialogue where both voices are talking honestly.

So, to answer your question, I think that books written after the TRC will have a much different flavour in terms of recognizing what is coming from a non-First Nations viewpoint about our history and about our relationship.

Can you give an example?

At the beginning of the book, there's this little epigraph, where it refers to the bottles that [Bernadette] throws out in the ocean. She's put these messages in the bottles, and the message has four statements. Basically, I only have four ways of seeing: how I see me, how I see you, how I see me with you, and how I see you with me. And the difference is we used to write saying, I know how you see. And she doesn't know that. She doesn't know how they see her, or how they see the world, and that was the point. That's the biggest difference that will come; people will finally stop saying, 'I have you figured out.'

Try to know the other, but never assume to know the other.

Who did you write this book for?

I think primarily, to be honest, I wrote it for non-First Nations people. For two reasons: Colonialism as a legacy in our country is not simply going to fade away on its own. It's not a matter of just waiting for time to erase it, nor is it correct to think that indigenous people are the only ones who need to be decolonized. Non-indigenous people, too, need to actively insert themselves into the process of confronting the colonial legacy, and their privilege, and by questioning things like the idea that's deeply embedded in us as non-First Nations people, that our ways of knowing and seeing and being are superior.

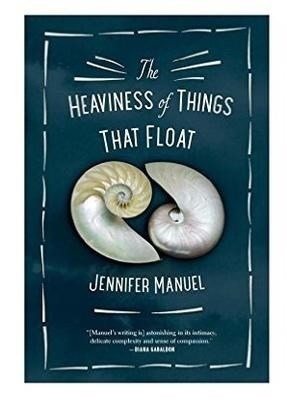

• ‘The Heaviness of Things that Float’ is out now on Douglas & McIntyre. $22.95, paperback.