September has brought the kind of news the Musqueam Indian Band has hoped for since it has struggled to build up its people and provide for its future generations.

The provincial government is about to give the 1,300-member band the green light to build a massive residential development on its land in the University Endowment Lands.

“Finally” is how Chief Wayne Sparrow welcomed the news.

The decision has yet to be made official but Peter Fassbender, the provincial minister responsible for deciding whether the project goes ahead, said he was satisfied it should proceed.

“From my point of view, the work has been done,” he told the Courier earlier this month, noting some legal steps and bylaws still need to be enacted before he signs off on the project. “When those bylaws are brought forward for me to sign, I see no problem with that moving ahead in a fairly timely fashion.”

The decision is significant for the economic future of the Musqueam, and it also marks the first time in the histories of the city and endowment lands that a First Nation is behind a major development on its own land in Vancouver.

The project includes four 18-storey highrises, several rows of townhouses and mid-rise apartment buildings, a community centre, a childcare facility, commercial space for a grocery store and restaurants, a public plaza, a large park and wetlands area.

All of it will be spread over 21.4 acres of what is now forest along University Boulevard, bounded by Acadia Road, Toronto Road and Ortona Avenue.

It will mean an estimated 2,500 new residents to the area, bringing an increase in traffic to an already congested section of the endowment lands.

The population increase, anticipated traffic problems, the height of the towers, calls for affordable housing and the destruction of trees were complaints heard at public meetings.

The complaints were not uncommon for a development of its size, as large projects in Vancouver such as the redevelopment of Oakridge, the construction of the Olympic Village and the renewal of neighbourhood plans have shown.

What’s different about this project is the property is owned by a First Nation and under the jurisdiction of the provincial government. City council had no direct say on whether it was a good fit for the community.

At a public meeting in May, Jay Mearns of the Musqueam Capital Corporation told endowment land residents the project will be a “game changer” for Musqueam people.

“These type of projects will allow us, for a lack of a better term, come up to the standards that the rest of Canadians currently enjoy,” he said from a lectern at the University Golf Course, emphasizing the band’s need to improve its high school graduation rates, build more housing and address health concerns on its main reserve in southwest Vancouver.

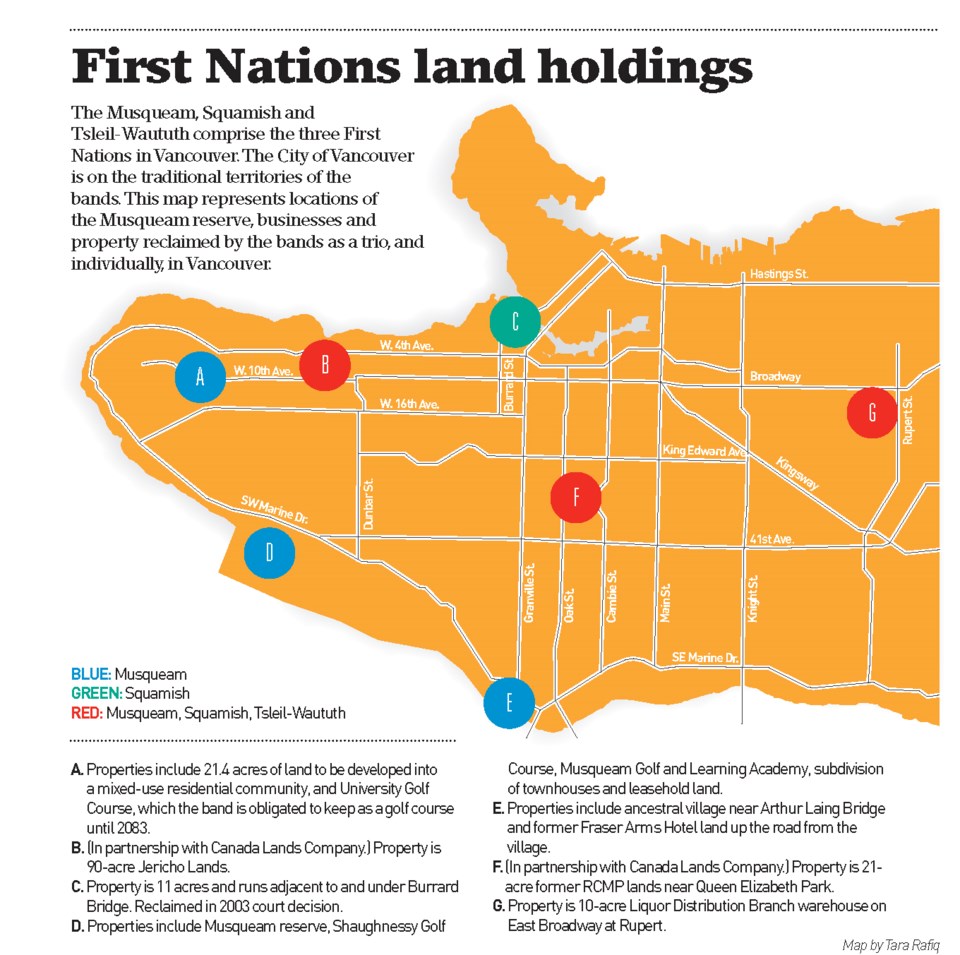

The project is the beginning of the Musqueam’s foray into the large-scale development world in Vancouver. The band is also working with the Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh nations to develop 121 acres of some of the most prized property in the city, including the 90-acre Jericho Lands.

The other parcels are the 21-acre Heather Street lands near Queen Elizabeth Park and the 10-acre Liquor Distribution Branch warehouse property on East Broadway. Total value of the 121 acres, once redeveloped, is estimated to be in the billions of dollars.

The federal government’s commercial property arm, Canada Lands Company, holds an equal interest in the Heather Street property and 52 acres of the Jericho Lands; the remaining 38 acres of Jericho is owned by the bands.

Significant fact one: There is no other entity in Vancouver that has that much property slated for redevelopment.

Significant fact two: The collection of land is in the nations’ hands because of an unprecedented business partnership that didn’t seem possible years ago.

After renewing ties during the 2010 Winter Olympics, the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh joined together to reclaim lands instead of battling governments and each other in the courts, or waiting out a treaty process.

It’s new ground for the bands, for city officials and residents in a city already seeing big changes to neighbourhoods. For politicians, they will be making decisions on First Nations projects at a time that reconciliation efforts at all three levels of government are central to their agendas.

Incidentally, the chunk of endowment lands to be developed by the Musqueam was returned to the band in 2008 by the provincial government as part of a reconciliation package. The University Golf Course lands and the land on which the River Rock Casino was built in Richmond were included in the deal.

Which leads to this question: Do governments’ reconciliation commitments with First Nations trump residents’ concerns when it’s decision time on a project proposed on indigenous land?

Fassbender said it wasn’t a factor in approving the Musqueam’s endowment land proposal, adding, “there wasn’t any additional pressure that, ‘Boy, we better do this, or else.’ I didn’t feel that, and I didn’t get that from the Musqueam.”

Mayor Gregor Robertson, meanwhile, doesn’t have an answer to the question as he awaits what could be years of conversation with the bands before rezoning applications are decided on the jointly owned 121 acres.

“It’s new territory for all of us, and we’ll see as it rolls out,” said the mayor, noting Vancouver has formally recognized the city is on the unceded homelands of the three nations. “They want this to be a great city, with fantastic neighbourhoods, too. I think there’s a lot of shared perspective on how this goes. It will be unique. We haven’t been through anything quite like it before.”

Neighbourhood watch

Questions about reconciliation and other topics related to the Musqueam’s endowment lands project were on the minds of residents who attended the public meeting in May at the University Golf Course.

About 80 people showed up, including Donelda Parker, who was examining the display boards for the project before the meeting got started. The retired faculty member at UBC lives about a five-minute drive from the property, and is worried about an increase in traffic.

“It’s going to be really chaotic along West Boulevard, so all the more reason to have a really fast way of getting out to UBC —that’s why a subway makes sense,” said Parker, who believes that as Vancouver grows, more density in the area is inevitable. “But I would hope there’s enough low-priced, lower echelon living space for staff members at UBC and faculty and students because they can’t afford to live nearby. It’s too costly.”

The project calls for “affordable workforce housing” and a mix of rental units throughout the development. Traffic and affordable housing may concern Parker but overall, she said, she supports the project and is behind the Musqueam band.

“Sure it would be good to have the forest continue forever and ever but I think that’s unrealistic,” she said, before making her point about the ownership of the land. “We were the nasty people who came in and took things over, so I think we have to be fair.”

A man who identified himself as “Philip from Acadia Road” was also checking out the display boards and examining a model of the development.

“I think it’s a disaster for the neighbourhood,” he said, when asked his opinion on the project.

Courier: Why?

“It doubles our population,” he said, adding that he believed the land should have never been returned to the Musqueam. “I don’t care who owns it, but it should have never been given to them, it should have never been given away. It belongs to the province, it belongs to the Crown. I don’t care who has it. It should have never been alienated. Period.”

Courier: The Musqueam would argue they’ve always had title to the land.

“Unproven. So is my house, so is your house, so is the whole of Vancouver. Why does anybody give any attention to that? It’s historical, it’s not real, it’s not real time.”

Courier: But development is happening across Vancouver. The construction of the Olympic Village is an example.

“That was industrial land. That was a waste area. This isn’t a waste area, it’s natural forest.”

Going corporate

That type of perspective isn’t news to Musqueam Chief Wayne Sparrow, who knows certain people are set in their ways and are reluctant to change.

His focus is on the well-being of his 1,300 band members and having his nation one day become self-reliant. To do that, he said, the band needs to generate cash flow by creating projects such as the endowment lands development.

“This is going to be the first one, and I keep telling our band members that if we do it right, we should be able to look after this generation and future generations,” he said by telephone as he drove his truck to drop off a load of fish to a customer.

Sparrow is a fisherman and is on the water anytime he gets a chance. He recalls agents of the federal government telling the band long ago that it could live off the sea and not have to rely on land development, or oil and gas projects like other bands in B.C. and across the country.

That hasn’t worked out, he said.

“We’ve had nothing but fights with the federal government and commercial fishing industry. They restrict us so bad that we can’t be self-sufficient.”

Looking to shift its economic development approach in the mid-1990s, the band tried to build a casino on its land near the Vancouver International Airport. The provincial government rejected the proposal.

The fact is, though, the Musqueam is one of the wealthiest bands in the country, particularly because of its holdings and interest in numerous properties in the Lower Mainland.

Recent additions are the endowment lands and others tied to the 2008 provincial reconciliation agreement, plus the 121 acres acquired in Vancouver with the two other nations.

The Musqueam owns the Shaughnessy Golf Course, Musqueam Golf and Learning Academy, the former Fraser Arms Hotel property in Marpole, a chunk of land near the Arthur Laing Bridge, subdivisions of townhouses and homes and land in Richmond, Burnaby and West Vancouver.

The band also signed a deal with B.C. Pavilion Corp in 2013 to obtain lease revenue from Paragon Gaming’s casino and hotel complex being built adjacent to B.C. Place Stadium.

The band’s financial statements ending March 31, 2015 show all revenue from government and self-generated revenue from mechanisms such as rent, leases and investment income totalled $44.6 million. Expenses were $20.8 million, for a surplus of $23.7 million.

Sparrow wants to boost revenues, and the band realized after acquiring the endowment lands and others under the 2008 reconciliation agreement that it had to seek out experts in business development to help deliver economic gains.

The acquisition of the 121 acres of land in Vancouver only compounded the need for Musqueam to separate the work of the band council with its development portfolio.

“We don’t have the expertise in the community to be dealing with big huge projects like this,” Sparrow said. “It’s a new arena for us, and we want to be sure to get the best advice.”

In 2012, the band created the Musqueam Capital Corporation, which is overseen by a board of directors that includes business executive Denise Turner and former B.C. premier Mike Harcourt.

The corporation is led by the band’s former chief financial officer Stephen Lee, who is CEO. Doug Avis is the corporation’s vice president of real estate. He joined the Musqueam corporation from the Surrey City Development Corporation and previously worked 18 years for the Canada Lands Company, which has a financial interest in the Jericho and Heather Street lands acquired by the three nations. Mearns is the corporation’s operations manager.

The three members spoke to the Courier in June at the corporation’s office on the Musqueam reserve in southwest Vancouver. The meeting occurred in a small boardroom dominated by a table on which almost half of it was taken up by the model of the development proposal for the endowment lands.

“You could say Musqueam is starting to become equity rich but they don’t have any cash flow,” Avis said of the band’s recent land acquisitions. “That’s what our objective is, along with all of the sustainability and employment and cultural objectives, is to turn this into cash flow. And that doesn’t mean just selling the land. That means creating an income stream by developing rental properties that will produce income every year.”

Sparrow, Mearns, Lee and Avis made it clear the end goal of the projects is to create opportunities for Musqueam’s young people and inspire them to pursue higher learning and take advantage of what’s in front of them. Lee and Avis are not Musqueam members but say they hope one day to be replaced by band members.

“We’ll make money on the developments, there’s no doubt about it,” Mearns said. “But that’s not really where the big value will come from. It’s how we raise the entire community capacity as a result of these projects and develop people to not only get careers as carpenters, plumbers, planners, engineers, doctors, lawyers — whatever — but it’s also to have people go out and develop their own businesses and get their own contracts.”

Mearns told a story about a Grade 10 Musqueam girl who was curious about the model of the endowment lands proposal. He asked her what she wanted to be when she grew up. She replied that she had an interest in early childhood education. Mearns pointed to the development’s childcare facility.

“I said here’s your end target, here’s your goal — you could be running that in 10 years. Get your education, get your certification, eventually get your administration degree so you could run something like this. And she was completely inspired. She took a photo and texted her friends and said, ‘Here’s where I want to work.’”

Working together

There’s another story Mearns, Lee and Avis say is worth telling but believe it would require a separate article to tell it properly. It’s the story of how the Musqueam, Tsleil-Waututh and Squamish put aside their differences to buy 121 acres of land in Vancouver.

Those differences were rooted in the federal government setting up the reserve system in Canada, which Mearns said left bands “to fight over crumbs and, as such, created a lot of protectionist approaches to keep track of our little piece of the pie. And what that did was create an unwillingness to work together.”

That animosity subsided during the 2010 Winter Olympics, when the three bands joined with the Lil’Wat First Nation and signed an agreement to showcase their culture and histories to the world during the Games.

A business partnership followed.

“We eliminated political agendas and just talked commerce,” Mearns said. “But it all started with us having to revisit our familial relationships and understand as Coast Salish people that we all come from one person.”

Squamish Chief Ian Campbell, whose nation has a population of about 3,600 people, remembers the decision to work together this way: “We said let’s stop that self-defeating behaviour of competition over scarcity of resources and move towards collaboration where we’re now focusing 33.3 per cent each equal partnership on these business opportunities.”

Added Campbell: “It was not easy, I’ll tell you. It has taken generations of effort.”

Campbell was sitting on a bench along a waterfront path near the Burrard Bridge when he spoke to the Courier. The setting was on the edge of an 11-acre property the Squamish reclaimed in 2003 after lengthy court battles.

Those battles involved the Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh, which challenged ownership of the property.

“It cost millions of dollars [in legal costs], it had taken decades to achieve and unfortunately it was very divisive amongst the three nations,” said Campbell, noting the government forcibly removed the Squamish from the land in 1913 and burned the village to the ground.

Campbell said the Squamish originally proposed building two towers, possibly rental, on the west side of the bridge. Profits from that first phase would be used to build a mixed-use development on the east side of the bridge.

That project is on hold because, as Campbell put it, “our team is pretty stretched.” Unlike Musqueam, the Squamish band has yet to create a business arm, but wants to. All three nations, meanwhile, have created a business development team to steer the 121 acres of land in Vancouver through city hall’s zoning process.

Campbell and Sparrow said it will be some time before the bands decide what they want built on the three parcels. Both chiefs say it will likely be a mix of housing, with possibly an information technology component on the Liquor Distribution Branch lands.

But Sparrow said Mayor Gregor Robertson and the public shouldn’t expect the developments “to solve the affordable housing issue in Vancouver.”

Sparrow said he understands the public’s curiosity over what will be built on the properties, particularly the biggest and arguably most prized land at Jericho. He said comments made by David Eby, the NDP MLA for Vancouver-Point Grey, in the media about the nations’ plans for Jericho have amounted to “scare tactics.”

“He’s never said one word to me, except on Aboriginal Day, and he’s coming out saying we’re building highrises and working with Chinese investors,” the chief said. “If we’re doing that, find out from us. Don’t put scare tactics out there for the people of that riding when you haven’t talked to us.”

Added Sparrow: “If he came and talked to us, and we turn around and say, ‘Oh yeah, we’re going to build highrises and then we might put in a casino and we might do this and that,’ then go to your residents and say, ‘Oh man, these guys are in left field.’”

Eby told the Courier the concern he has about the Jericho Lands is that the housing built there will be unaffordable for people who work and live in Metro Vancouver.

“And that essentially what will be built is luxury condos for international investors,” Eby said. “I’ve often spoke about the worst case scenario, which is another Coal Harbour, which is a bunch of vacant investment condos that don’t go any distance to helping us solve our affordability crisis that we face in the region.”

Added Eby: “That was my concern before the property was purchased by the First Nations. It remains my concern.”

Eby wants to see some affordability component on the Jericho Lands but clarified, “[I don’t think] it’s on First Nations to ensure affordability for the broader community. They have their own housing challenges that they need to work on as a result of the colonial history of British Columbia.”

Buy-back policy

The progress made by the three nations to reclaim the 121 acres of land in Vancouver is not without some controversy, or at least some teeth gnashing from the bands.

That’s because the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh, whose traditional lands overlapped before colonialism, are paying for land that once belonged to them.

“A lot of our people are still upset, including myself, over why we are buying our own land back,” Sparrow said. “That’s the elephant in the room. But at the end of the day, we’re moving forward and hopefully we’re going to create wealth for our community.”

The total cost of the Jericho Lands, which was a complex deal involving federal Crown corporation Canada Lands Company, mortgages and government payouts, came in at around $717 million.

Campbell understands his members’ concern about purchasing the lands but argued the buy-back method was the best route to prosperity.

“There’s risk if you’re going to litigate, there’s risk if you’re going to do treaty. You could always blockade and use public dissension and civil disobedience. You could do nothing.”

Or, he continued, the band could create certainty by purchasing the land with partners and look to make a profit and pour it back into their respective communities.

“Each of the nations wants to move away from the Indian Act,” he said, noting the legislation was not designed to create affluence. “It was created to subjugate First Nations’ people and put us under a model that basically manages welfare. We want to manage wealth.”

‘A big pile of land’

Management of that wealth could take some time.

The bands are being told it could take two to five years for a proposal to work its way through city hall.

“I don’t think most people realize the magnitude of this for the city, or for the First Nations,” the mayor said of the 121 acres. “It’s a big pile of land.”

Ultimately, Robertson said, it’s up to the Squamish, Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh to decide what it wants built on the lands, although the mayor told the Urban Land Institute in a speech in June 2015 that he didn’t want to see the Jericho Lands solely become “an enclave for the wealthy.”

The Musqueam, meanwhile, are anxious to get started on its project in the endowment lands, with Sparrow suggesting the band could break ground next spring.

“We’re looking forward to it,” the chief said.

Note: The Courier made repeated requests via telephone, text and email to interview Chief Maureen Thomas of the Tsleil-Waututh First Nation for this story but the band was unable to provide her for comment.

Next week: the Courier looks at policing.

[email protected]

@Howellings