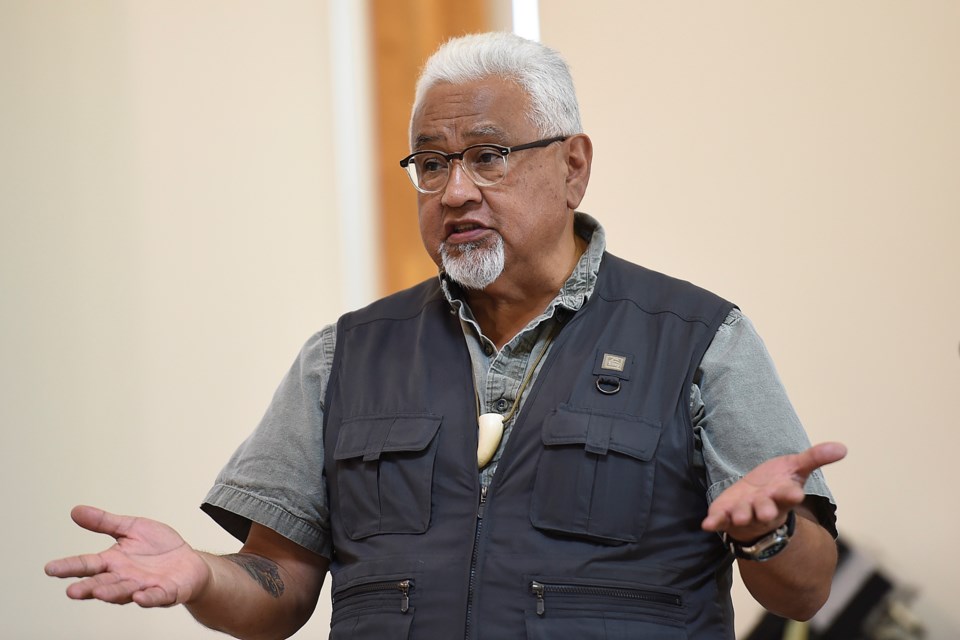

Shane Pointe is full of stories.

In little more than an hour, he told several in his even-paced, captivating way before he got to talking about his job as the Vancouver School Board’s “knowledge keeper.”

Pointe, 61, was seated in the shop class at Magee secondary, where he was carving a three-foot long model canoe from a piece of cedar. It would later be dedicated to the school as part of the school’s centennial.

What would he name it?

Without hesitation: “Endeavour.”

And so began his story about the 62-foot race canoe his grandfather Leonard Point of the Musqueam Indian Band built in the 1960s, also called “Endeavour.”

“Wow, that’s thought, that’s deep thought,” he said of the name choice, noting the time period and struggle for First Nations people. “When people think about us, we’re always less than. But endeavour — wow. Endeavour to achieve, endeavour to achieve success through knowledge.”

The canoe for Coast Salish people has been a practical transportation vehicle for thousands of years, using it to travel up and down the coast for trade. The canoe is also deep in symbolism for what it represents to First Nations.

“It’s a container not only for travel, but it’s a container to put one’s life experiences and education into so the individual can succeed from moving from A to B, regardless of the conditions of the sea,” Pointe said.

The story about the canoe led to one about the late Willy Seymour of Kulleet Bay near Ladysmith, who taught Pointe the importance of bringing passion to his teaching and emotion to his voice when speaking to a crowd.

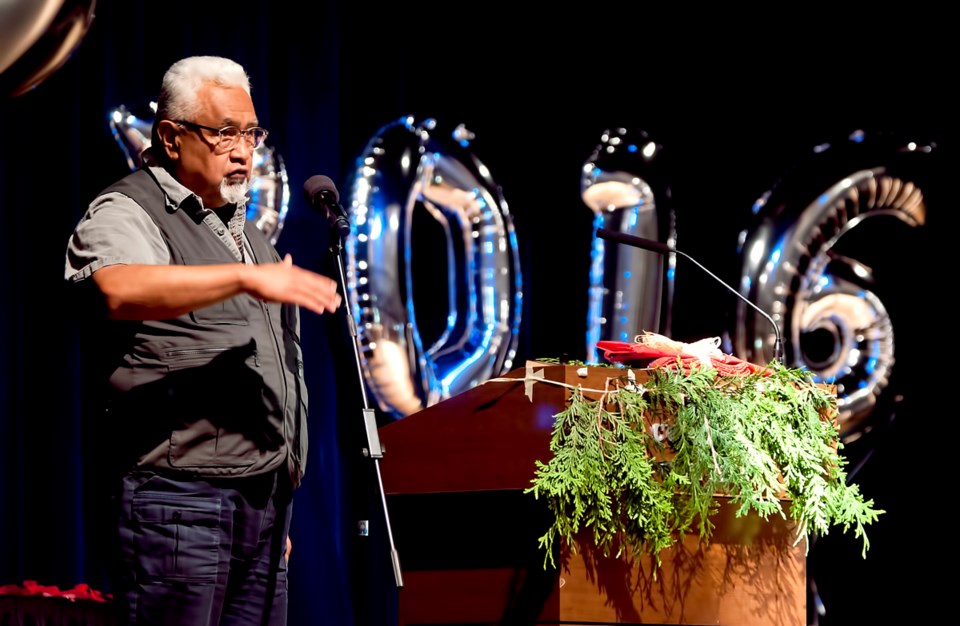

It’s served him well, as the Courier observed in the shop class, at a school board event at the Musqueam Cultural Centre and at a high school graduation for Aboriginal students in June, where he praised the teenagers for their perseverance.

“You’re the luminaries, not only of your own families but you’re luminaries for all First Nations people,” he said from a stage, projecting his voice to the graduates seated in front of him at the Italian Cultural Centre. “I want to welcome you here to this moment. It’s a great moment, it’s a special moment because you have achieved, you’ve made it.”

As Pointe begins another year as the school board’s “knowledge keeper” — a position he describes as one where he discloses knowledge of the Coast Salish peoples language, culture and ceremony to students — he knows there’s value in what he does.

Student letters

But don’t take his word for it. Or the word of the superintendent, or teachers or school trustees. It’s the students who know best, he said, noting he received more than 400 letters from them in the past school year.

One student wrote: “Shane Pointe’s visit was very eye-opening. In class, we learned that children had to go through all kinds of torture in residential schools. But it felt like something I was just supposed to know. To hear the same words come from someone who knew people that had to experience it, made it feel more real.”

Another student, who also learned about the residential school system and the ancestral villages of the Musqueam, wrote: “I learned all of this and much, much more. Shane Pointe was great when he visited Eric Hamber. He was incredibly friendly, funny and informative. He did an amazing job and I look forward to any future visits from him.”

One more: “What I learned was First Nations people are cool and their ways are very Zen-like. I aim to strive to find ways like that, too. I also learned that First Nations had much success in the real world, and the media always aims to try and put the culture down by telling everyone about their flaws as a community, instead of saying their achievements.”

Those successes Pointe has talked about in classrooms include his relative, Steven Point, a provincial court judge and former lieutenant-governor of B.C. There’s also Steven Point’s wife, Gwendolyn, who is the chancellor of the University of the Fraser Valley, and the late Musqueam educator Norma Rose Point, who had an elementary school named after her on Ortona Road. Dr. Evan Adams of the Sliammon First Nation near Powell River is another successful indigenous person Pointe mentions.

“That’s now, that’s today,” said Pointe, whose surname has an “e” at the end of it because his father wanted to distinguish himself from the rest of the Point family.

Dalai Lama

Pointe can also be considered a success story: How many people do you know who were invited – twice -- to ceremonies to welcome the Dalai Lama to Vancouver?

The most recent welcoming was in 2014. A year later, the school board hired Pointe, who visited 46 elementary and secondary schools during the 2015-2016 year, speaking to Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal students.

He is quick to point out he is not alone in his pursuit to educate non-Aboriginal students about a history kept from the curriculum for decades. He credits classroom teachers and the teachers and support workers connected to the district’s Aboriginal education enhancement program for priming students before his visits. Support for indigenous students, who totalled 2,100 from 600 different bands in the past school year, has been available in the district for several decades.

“The level of knowledge the students have about First Nations people is exceptional,” Pointe said, describing the school board’s commitment to support Aboriginal students and teach First Nations history as “cutting edge.”

He used that description before he opened a ceremony in June at the Musqueam Cultural Centre, where school officials, teachers, support staff and politicians gathered to renew the agreement of the Aboriginal enhancement program. The agreement was first introduced in 2009 and its purpose was to integrate Aboriginal culture in schools and create an environment where Aboriginal students can achieve success.

Don Fiddler, the principal of the district’s Aboriginal education program, was in the audience when Pointe welcomed guests to Musqueam to renew the agreement.

Fiddler, who is of Metis-Cree heritage, hired Pointe and has kept him on this school year for three days a week. Fiddler noted Pointe’s deep understanding of the protocol and procedures of the Musqueam and Coast Salish peoples and his ability to articulate that history to students. He described Pointe as a bridge between the school board and local Aboriginal culture.

“He projects a kindness and a gentleness, and enjoys speaking to very young children and that’s been very helpful,” he said, noting he isn’t aware of any other school district in the province that has a person dedicated to this work. “I can say that generally the kids in Vancouver are getting a good understanding of Aboriginal culture and the teachers are certainly very supportive. And Shane adds to that.”

Residential school

Pointe, who grew up in Nanaimo where he finished school with “a solid Grade 9 education,” came to the job after working for several years as a support worker in schools, in prisons, with residential school survivors, single mothers and as a drug and alcohol counsellor for the Musqueam Indian Band.

He’s seen a lot of life and believes there’s been a shift in society, where Aboriginal people are genuinely part of a conversation that didn’t exist when he was a young man.

That shift, he said, is evident at the school board, which opened an Aboriginal focus school in 2012, and at city hall, where city council declared Vancouver to be the first city in the country to become a city of reconciliation. Council also formally recognized that Vancouver is on the unceded homelands of the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh nations.

The city has a manager of Aboriginal relations and four years ago created the Urban Aboriginal Peoples advisory committee. City staff and politicians also meet regularly with the Musqueam and other nations.

“We’re right up there with bike lanes for Gregor Robertson,” joked Pointe, before praising the mayor’s commitment to reconciliation with indigenous people. “The mayor has done excellent work in engaging Musqueam and engaging all First Nations people who live within his boundaries. And he’s sincere in what he’s doing. Of course, he has many other responsibilities but he’s paying attention and he’s going, ‘No, we need to do this.’ He had not one day of reconciliation, he had a year of reconciliation.”

But is it authentic? Is it genuine?

“It’s not a tidal wave, but it’s a big wave,” he said. “The tide’s coming in. Let’s use a First Nations’ metaphor, the tide’s coming in. Awesome. Yes.”

One more story from Pointe:

Back in June, he spoke at Lord Byng secondary’s graduation ceremony. Three days later, he was at a bus stop. A man he estimated to be in his mid-40s pulled up in his car and got out.

“He says, ‘You’re Shane Pointe.’ And I said, ‘Yes.’ He says, ‘You spoke at my kid’s graduation and what you said moved me.’”

Pointe paused, then repeated some of what he just said. “The guy said, ‘I was moved by what you said, what you did.’”

How did that make Pointe feel?

“Awesome, of course. A middle-aged white guy. Wow. How often do you go up to somebody and say, ‘You know, that was emotional. You moved me.’”

Pointe pounded his fist on his chest.

“Awesome.”

[email protected]

@Howellings