A war for the planet is being waged in northeastern British Columbia.

In one corner stands a formidable tag-team: the Province of British Columbia and the oil and gas industry. The other side is equally impressive: determined, never-say-die environmental activists, many from First Nations communities.

The stakes are high: natural resources; billions of dollars; the sustainability and health of humans, animals, and the environment.

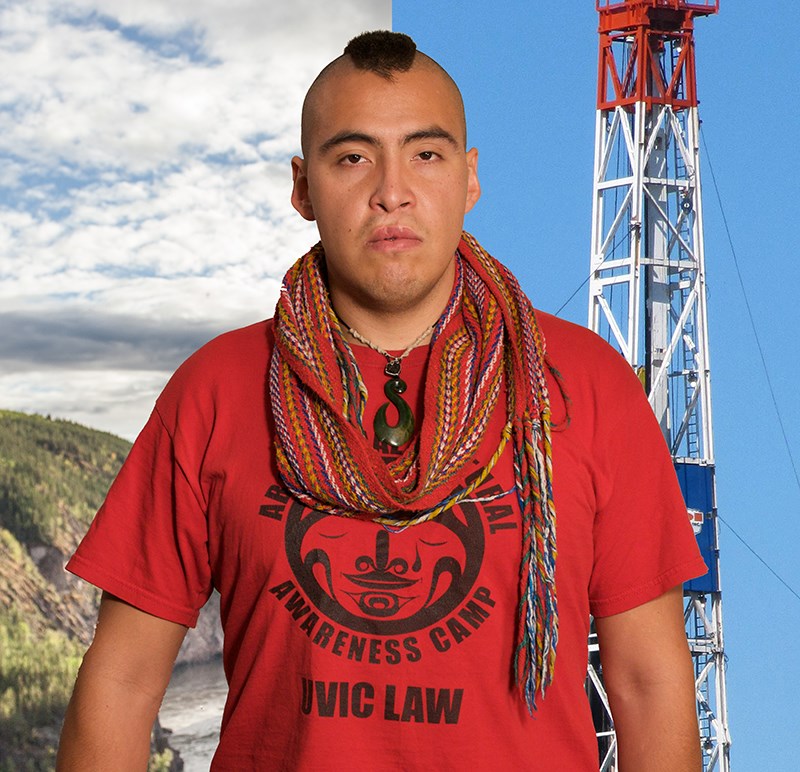

Five years ago, few Canadians were even aware of the existence of this war, so one BC man – Caleb Behn – granted permission to a couple of local filmmakers to train their cameras on his life, and tell the story of the war through his eyes.

Behn is a Dene Nation activist, and, when filming began, a second-year law student.

Behn’s father is a survivor of the residential school system, and vehemently opposed to the oil and gas industry. His mother works in the industry, striving to change it from within.

Before they’d met Behn, filmmakers Damien Gillis and Fiona Rayher were keen to make a film about hydraulic fracturing. But in Behn, Gillis and Rayher found a charismatic character whose personal fractures mirrored the environmental issues he championed.

“Once we started talking to him and met him in person, we recognized that he was an eloquent, intelligent young fellow who not only knew a lot about the industry, but was willing to welcome us into his world and introduce us to his family, and would also potentially make an ideal character, and subject, through whose eyes we could examine these issues,” says Gillis.

“As cheesy as it sounds, I saw a leader in the making,” says Rayher in a recent phone interview.

The result of five years of filming is Fractured Land, a feature-length documentary that premiered at last year’s Hot Docs and won the award for Best BC Film at the 2015 Vancouver International Film Festival.

It’s perhaps more commonly known as fracking, but no matter what it’s called, hydraulic fracturing is a controversial form of natural gas extraction in which a mixture of water, sand, and chemicals is blasted into shale formations to release methane gas.

Critics of fracking object to the toll the process takes upon the environment, particularly the water supply. There’s also a documented correlation between fracking and earthquakes.

Fracking bans and moratoria exist throughout Canada and countries all over the world – but not in BC, where the multi-billion dollar industry contaminates up to 11 billion litres of water per year, the bulk of it on parcels of land that the government has sold to the industry with (according to critics) minimal consultation with First Nations communities.

And so Fractured Landshines the spotlight on the complex issues swirling around natural gas extraction in BC.

Later this month, it will screen as part of Kwantlen Polytechnique’s KDocs Film Festival.

The film has served to make something of a celebrity of Behn, who is now a lawyer and the executive director of Keepers of the Water, an Aboriginal-led organization dedicated to protecting fresh water in the Arctic drainage basin.

This framing of Behn as a hero is reflected in the film’s official synopsis: “What would it be like to live alongside one of the shapers of human events, in their youth, before they transformed history?... [Behn] may become one of this generation’s great leaders, if he can discover how to reconcile the fractures within himself, his community and the world around him, blending modern tools of the law with ancient wisdom.”

Reviewers and festivals make much of the fact that Behn sports a mohawk and tattoos, hunts moose, and wears a business suit. In the film, he’s introduced to a group he’s about to address as follows: “Anybody who can throw a hatchet and sue you is a force to be reckoned with.”

Today, in addition to his role as executive director of Keepers of the Water, Behn is the lands manager for the West Moberly First Nations, which is one of two nations still opposing the Site C dam project in court.

“I spent a lot of time while I was in law school and afterwards raising awareness, but my true skill set, I think, is actually the work. The head-to-head, face-to-face, technician-to-technician engagement of legislation, on policy, on the technical aspects of given development,” Behn told Reel People in between meetings in Vancouver.

The stakes in this war for the planet are high, says Behn.

“Nowadays, our destructive potential is unparalleled. In the old days, a man wielding an axe could knock down a forest in a few months. Nowadays, a man wielding a modern feller-buncher and skidder can knock down a forest in an afternoon,” says Behn. “Think of all these dynamics, and the law of unintended consequences means that our extractive development is putting us in a very dangerous place.”

In Fractured Land, Behn “was trying to convey that, but not just using science and talking heads and complex graphs showing the mechanisms of developmental toxicity and their implications. It’s got to be a bit more subtle.”

And so Behn shared a lot of himself in Fractured Land. We see him studying; shaving his mohawk; hunting; sitting beside as his father as the elder Behn addresses the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

We learn about Behn’s successes and failures; his history of abuse; his infidelities in personal relationships.

Behn says he’s suffered for revealing as much as he did.

“I came into my emotional maturity after 29, and there is a trail of broken hearts behind me,” says Behn. “My reputation is terrible in certain circles. I suffer lateral violence regularly, and I internalize the shame, and I had to figure a way not to kill myself while the film was coming forward into production.”

Behn is quick to point out that filmmakers honoured him with his film; still, he contends that, as a result of the film, he’s found himself in what he describes as a challenging place.

“[That’s] the price of being honest in a world so rife with dishonesty,” says Behn. “That’s the price of being real in a world of bias, and I’ll pay the price, but I didn’t realize how much it would cost.”

His one regret with the film is that it doesn’t do enough to tease out and convey the correlation between the violation of land and the violation of the vulnerable, especially women and children.

“And I would suffer 10 times the consequences if we could convey that connection in a very meaningful way, because it’s one of the greatest modern injustices,” he says.

Behn has travelled extensively with the film as it screens at festivals, participating in Q&As and learning from audiences. He says he’s learning that people feel disempowered; that people are frustrated; that people, although open to education, have difficulty coming to the table without preconceived notions.

“I’m learning to be humble before the plight that we’re all sharing in,” says Behn.

And somewhere between his work for the planet and his ongoing learning, Behn is working on a book that will ultimately be published by HarperCollins.

The memoir will be an analysis of larger issues using the only things Behn says he has a right to: his story, his thoughts, his analytical capacities, and his experiences.

“I believe this province, and especially the northeast of this province, holds an as yet unexplored lesson of global significance, and I’m trying to use the book as a mechanism to learn from what’s happened in that territory, because it’s a rich history.”

• Fractured Land screens Feb. 20 as part of the KDocs Film Festival. Behn is scheduled to attend as special guest and keynote speaker. Tickets at VIFF.org