He does weddings and he does funerals.

With funerals, he says, you’ve got to start with a joke.

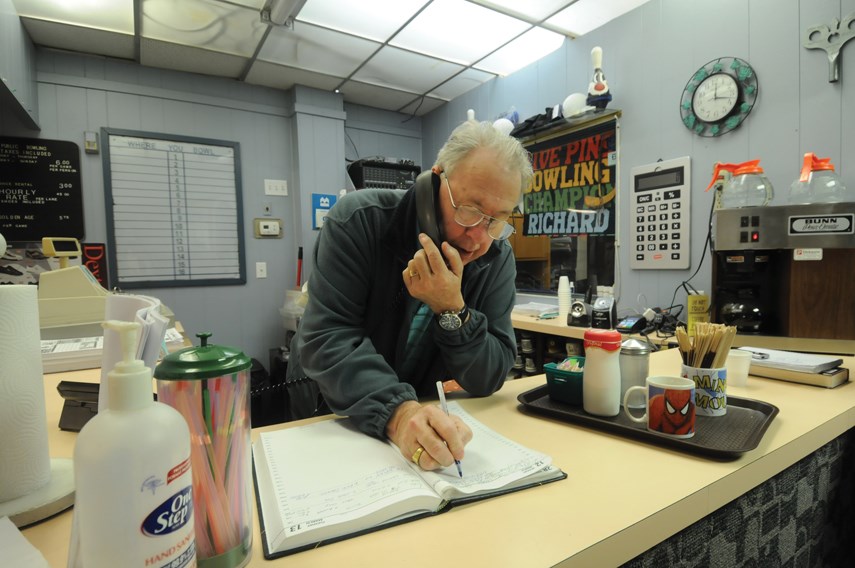

Standing behind the counter at North Shore Bowl on West Third Street, Richard Grubb, 72, seems as much a part of the joint as the laminate lanes, the plastic pins, and the coffee we’re sipping out of tiny Styrofoam cups.

He’s still explaining the psychology of funeral comedy when a delivery guy interrupts to ask about the chair blocking the delivery room.

“Take that chair and throw it at this guy!” Grubb orders, pointing to me.

We met 30 minutes ago, but like just about everyone who time-warps down those stairs, Grubb and I are old friends.

He knows the place. He knows who wears a size nine and “who’s a pain in the ass.”

In 2014, the North Shore News called North Shore Bowl: “the last pin standing.” That pin is about to topple, Grubb reveals.

“I’ve been in bowling 59 years, I’ve been here 35 . . . I’ve had enough now.”

There’s a For Sale sign out front and a buyer could swoop in, throw down some cash and close the doors at any time. Even if it doesn’t sell, by May 31, 2020, the North Shore will lose two institutions: the bowling alley and Grubb. The old pin king has given that date as his final frame.

Grubb’s been an alley cat since he was 13 and a buddy pried him away from a pinball machine at Commodore Lanes on Granville Street and forced him to pick up a ball.

He set pins for five cents a game and gave just about every nickel back to the Commodore so he could bowl against his friends (they were no competition, he confides) and their parents.

“I told them I’d beat ‘em. . . . I was a cocky bugger,” he adds, a wolfish grin spreading across his face.

He was Vancouver’s other King Richard. Mr. Commodore. Mr. Wonderful (and that was before pro wrestler Paul Orndorff came along and stole his nickname, he says).

“The problem was I was so young, I was so good so fast . . . I lost interest.”

He eventually won three national championships but not before realizing that while he was good, he wasn’t nearly as good as he thought he was.

Grubb started as assistant manager at North Shore Bowl in 1983 and ran the place by the end of the ‘90s.

The lanes are open 364 days a year and Grubb is usually there from the first loft to the last fudged scoresheet.

He takes the odd Sunday off, he says: “if there’s no birthday parties.”

It’s sad to think about walking away from it, Grubb says, reflecting on the adults with special needs who pack the place every Thursday night for the Special Olympics.

“It’s not really the bowling,” he explains. “It’s the camaraderie. They just love being here talking to everybody.”

In a few hours the air will be thick with 3.5-pound thunder and the persistent rumble of the machines behind the lanes. But the place is oddly quiet Friday morning as Grubb reflects on the miles he’s walked in rented shoes.

“Those machines are 55 years old. They’re only supposed to last 30.”

He’s talking about the pinsetting machines but he could be talking about anything in the place. He could be talking about the place.

“It’s kinda sad bowling’s going down,” he says. “Women used to bowl morning, afternoon and night. Now a lot of them can’t afford it. . . . How the hell can people afford to even live here, I don’t know.”

Grubb remembers the era when North Shore Bowl was better than $10-a-day childcare.Walking through the backroom today you can see the cages where young mothers deposited their babies before heading out on the lanes. There was a crib, a row of desks, and horizontal slats where toddlers looked for their mothers and maybe rattled a cup or two along the bars.

“Women made the business,” Grubb says.

Women strike!

On Wednesday mornings women between the ages of 30 and none-of-your-business take over North Shore Bowl.

Grubb ambles over to one team and asks if the reporter is bothering them.

“You bother us, go back,” Henny Bohlen retorts.

“I’m gonna go somewhere where someone likes me,” Grubb tells the women.

“Pack a bag,” Cathy Kuzel calls after him.

They both grin. That was a good one.

“He can be really gruff but he has got the biggest heart,” Kuzel says once Grubb is safely out of earshot. The two have history, as Kuzel once volunteered at the counter when Grubb was swamped with wall-to-wall birthday parties. Off the lanes Kuzel is a business development strategist.

“I love my job,” she says. “This is the break.”

Asked how long she’s been bowling there, Bohlen’s eyes flit toward the humming lights and does the math.

“My husband passed away . . . 18 years ago,” she says. “18 years,” she answers.

North Shore Bowl is a good place for comfort, explains teammate Darlene Hilden.

“It’s just a place where if you even have any issues . . . you’ve got moms everywhere.”

Asked why they keep coming here, Hilden smiles.

“We’re North Shore people,” she says, by way of explanation. “I’m 60 this year and I’ve all my life been coming here.”

As she’s talking, Bohlen, 86, notches her first strike of the day.

Sauntering back, Bohlen holds out her hand for a high-five and then another one.

“I gave you some,” Hilden tells her.

“I want more,” Bohlen replies.

She gets more.

These get-togethers used to happen at Thunderbird Lanes and at Park Royal but subsequent closures presented the bowlers with a dilemma, Kuzel says.

“It was either go across to Burnaby . . . or we switch to five-pin,” she says.

They switched.

With the closure of North Shore Bowl imminent, the league might be able to move to the six-lane, 10-pin bowling alley set to open soon in Central Lonsdale, but Kuzel isn’t sure.

“I think this is going to be the end of the end,” she says.

“We just get more and more people on the North Shore but less and less to do,” she says as a teammate picks up a pencil and marks a spare. “I’m up, excuse me.”

Ancient and modern history

First: a lie that tells the truth.

In the summer of 1588 King Philip II of Spain launched 130 ships carrying 2,500 guns against England. As the ships massed along the coastline, Francis Drake – who was vice-admiral of the English fleet – looked up from his bowling green and allegedly remarked: “I have time to finish my game.”

That quote has endured centuries not because it’s factual but because it feels true. On those nights where you’re throwing rocks, even the Spanish armada feels secondary.

While bowling has taken many forms in many countries, Purdue University bowling instructor Doug Wiedman traces the modern game to the holy rollers of the Middle Ages. Amidst church services the pins represented pagans and a good shot was a testament to the godliness of the bowler.

The Europeans who sailed to North America brought nine-pin bowling with them – although the godliness didn’t make it off the boat. Citing rapacious gamblers, the state of Connecticut banned nine-pin bowling in 1841. Ten-pin bowling, Wiedman suggests, was a born as a legal loophole.

“Ninepin? Certainly not! Officer, you can clearly count 10 pins on that lane.”

On West Third Street, the first ball cracked the first pin in 1961.

It was about a dozen prime ministers ago (if you count Pierre twice), back when the south side of the block was dotted with vacant lots and jukeboxes were dominated by singers named Dee (Joey Dee, Dick & Dee Dee, Dee Clark, Dion).

According to the recollection of onetime bowling alley owner Bud Cawsey, there were about a half-dozen cops between Deep Cove and the Lions Gate Bridge and two Lower Lonsdale bowling alleys within walking distance.

“The North Shore was sparsely settled at that time,” Cawsey recollected in a 1996 letter to the North Vancouver Museum and Archives. “I liked it just the way it was.”

Cawsey owned Inman’s Bowling Salon at 403 Lonsdale Avenue, selling it to Ron France in 1958.

Speaking with reporters in the 1970s, France complained of inflated rents and competing with “subsidized recreations like curling and tennis.”

“It’s always tempting to make more use of a building,” he remarked at the time. “Bowling does require an awful large area.”

In 1974, the headline read: Inman’s Epitaph: The End of an Era.

“France appreciates rather deeply the psychic impact that demolition will have on many of the older residents in Our Town,” the elegiac reporter noted. “But business has gradually fallen off . . . as the bowling boom of the 1950s has never really returned.”

You could hear a pin drop

North Shore Bowl endured because of good landlords, Grubb says, recalling a handshake deal that lasted years.

“If I’m not here, I don’t think anybody can run it,” Grubb says. “It’s not because I’m great, it’s just that I care.”

He also seems to love his work. Even a question like “How are you?” is loaded when talking to Grubb.

“Any better I couldn’t stand it,” he replies. “Any better I’d be you. Any better you’d be twins.”

He cleans up, he takes reservations and when a pin gets jammed in the elevator or a belt comes off the machinery, he or manager Neil Richards duck behind the lanes.

“Neil and I know by the noise what’s wrong,” Grubb says.

Whether it’s shovelling snow or telling a customer the way it is (“That customer ain’t ‘always right,’ that’s crap,” Grubb intones), he’s done what he could to keep the place going.

A few years back the restaurant above the alley “tried to fix the toilet,” Grubb says, putting the emphasis on “tried.”

“I come here one morning: water coming down here you wouldn’t believe. Like Niagara Falls.”

But after dealing with the mould and mildew and a restoration company, Grubb oversaw the installation of brand new lanes.

A few years after that he fell down near one of those lanes. He couldn’t get up.

Two days after his fall he had an operation that allowed him to keep walking and keep bowling.

“Isn’t that lucky?”

When bowlers walk in he mocks, flirts and cajoles, but he maintains that the most important thing he does is the first thing: “All you do, when they come down the stairs you say ‘Hi.’ That’s all.”

He’s got no problems with his longtime customers, he says. “They all know I’m full of shit.”

When he heads to Keremos it’ll be North Shore Bowl’s funeral. And time for a joke.

But, Grubb notes, behind a gas station on the outskirts of Keremeos there’s a little community centre.

And inside that? A bowling alley. He’s talking about rolling as the resident pro in Keremeos when the phone rings.

“North Shore Bowl, can I help you? . . . Who? . . . Sean?” Grubb asks.

He tells the caller it’s been the same phone number for 55 years but the woman seems determined to talk to Sean.

“This is a five-pin bowling centre,” Grubb insists.

“You wanna bowl?”