In part one of this series in the Vancouver Courier, we were introduced to Norma-Jean McLaren and her husband, Nathan Edelson. We learned that Norma-Jean has early stage Alzheimer’s. We also learned she is part of a clinical trial testing, through electrodes implanted in her brain, whether deep brain stimulation can improve memory capacity or at least forestall its decline.

The surgery and first follow-up assessment took place at Toronto Western Hospital. There would be four more assessments to follow over 2016, ending in December.

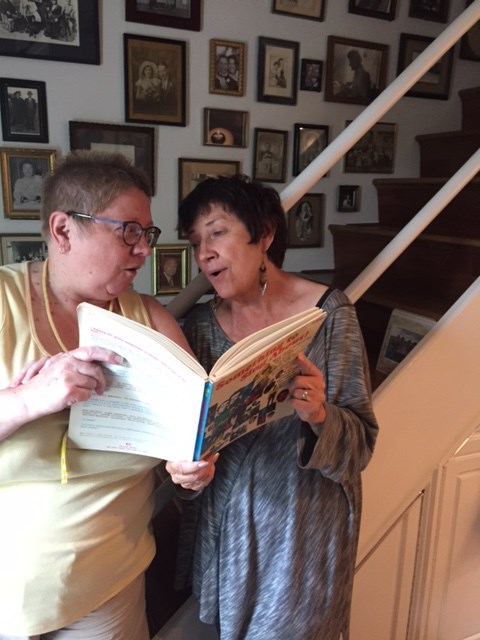

Wendy Bancroft, a former journalist who now leads workshops in guided autobiography, is one of roughly 25 friends who spend time with Norma-Jean doing activities she enjoys and that are known to improve memory and strategic thinking such as walking, singing, personal training and storytelling.

Wendy’s visits began by recording some of Norma-Jean’s life stories, but as their conversation kept returning to the clinical trial, the sessions shifted to a focus on tracking Norma-Jean’s progress over this year. This story picks up where part one ended — with Norma-Jean and Nathan returning to Vancouver, feeling optimistic about the direction they were taking.

February 17

Norma-Jean and I sit down at their kitchen table with a glass of wine, my notepad and recorder and start talking.

It’s a good day. She is warm, highly engaged, bright and confident — a description that captures the Norma-Jean loved by so many. Her personality, and the fact that she is so open about her condition, explains why so many friends are happy to spend time with her.

On this day, Nathan wants to share what he sees as tangible evidence of improvement. He tells me they had run out of a particular vitamin and Norma-Jean had been blaming herself. But then she realized the supply had diminished because Nathan had started using the pills as well. Nathan said this was significant on two levels — first that she was connecting the decreased supply to something she thought she had done and, second, she could see that not only was she actually not the cause of the problem, somebody else had screwed up — him. He smiles and adds, “And she said it with a certain kind of glee.”

February 24

Norma-Jean wants to walk and talk so we set out over the land bridge into False Creek, sitting to talk on a park bench.

She tells me she’s been doing a lot of walking with a lot of different people. I ask if she ever walks on her own and she says does, but only on a prescribed route. She says she loves walking with friends, but walking on her own makes her feel she has some control over her life:

“Being able to do that is such a gift to me. And I don't feel like I have that many gifts right now.”

She tells me she’s worried about her upcoming assessment at Toronto Western Hospital. She’s really hoping the voltage can be increased to the level where, at the first assessment, she was flooded with memories. They’d had to turn the voltage down because she was also flooded with unbearable heat, but by now, she hoped, her body would have adjusted. Still, she’s scared of experiencing that again and scared as well that she’ll stop the voltage increase too soon, perhaps sabotaging her gains.

Nathan posted in Facebook, “Fingers crossed!”

March 9, Toronto Western Hospital—Assessment Two

They travelled to see friends after this assessment, but Nathan sent back word that the voltage had been increased, just not as high as they had hoped. There was no memory flood.

April 13

Norma-Jean is depressed and fragile. Teary.

“I really feel um a bit lost… And uh… in the face of that, I have just to keep on going. But I feel like I'm losing so much and that I can't remember what I did yesterday. I can't remember what I need to... what I'm concentrating on. And I feel a lot of loss... I feel that so much goes out of my mind so quickly.”

To lessen her confusion, Nathan keeps a record of her scheduled activities on his computer calendar and Norma-Jean checks it frequently. He knows the level of activity adds to her confusion, but he also knows if she’s not occupied, she’ll get depressed and obsess about her memory loss, or zone out in computer card games.

It keeps Nathan busy attending to Norma-Jean’s schedule on top of his work as a consultant, but he’s convinced that having this stimulation is essential to her well-being — stimulating her intellectually and emotionally.

May 4

Norma-Jean and Nathan have been away on a holiday to Southern California. In the 10 days they were gone, they stayed in four different places. Norma-Jean frequently became confused about where they were, and sometimes, with whom they were staying. Nathan was concerned.

“The hardest one was when we stayed with our niece and her husband and the first evening, Norma-Jean pulled me aside and said, ‘I can't remember how I'm related to this person.’”

She is better than before the surgery, but it’s definitely not a straight up trajectory and she is hyper aware and self-critical about this. Never mind the bigger stuff, if she can’t find her keys or forgets what happened an hour or two before, she can quickly fall into despair.

Norma-Jean says she knows Nathan feels it’s important to “keep the faith,” to believe that everything is going to be all right and that, “each time we go back to Toronto, it will be better and better, but,” she says, “getting ahold of the loss is really difficult.” I ask her if she thinks her memory is worse now than before and she says, “No. I think I’m the same.”

May 18

I arrive at my regular time, 5 p.m., to find they have company — their grand-nephew, Stefan Reindl. Norma-Jean’s sister is Stefan’s grandmother — and is in an intermediate stage of Alzheimer’s. As Stefan told Norma-Jean, “My grandma can't remember what she was doing five minutes ago. And there's no sense that she's present in a conversation like you are. There's a glazed-over look on her face.”

During the evening, I had a chance to ask Nathan how he is doing. He says, “Mostly fine, but it saddens me, and every once in awhile I think of the possibility that it may not work and then what?” He is reassured by Dr. Lozano’s confidence that, if nothing else, deep brain stimulation will slow down or stop further memory loss, but he hurts for Norma-Jean and misses the woman he married — the woman known for her intelligence, for leading the way in conversations.

Nathan feels the memories are still there, but need to be triggered. When triggered there is “access to the memory pathways.” Her friends say she is more “present” in conversations and only rarely repeats herself. They observe that her memory loss increases when she’s experiencing physical pain and when she’s tired. Her memory improves when the event has emotional significance.

And sometimes, she just gets it right. On our May 22 visit, she told me, with a big smile, that she’d shown up for a hair appointment at 2:30 that day and, lo and behold, “That was exactly the right time!”

May 28

Nathan and Norma-Jean fly to Toronto for the third assessment with hope in their hearts that the tests will show improvement and that, this time, the voltage can be turned up to that first, critical, level. Stay tuned for part three of their Alzheimer Disease “journey.”

To follow Norma Jean's story from the beginning, visit vancourier.com.