There’s an advertisement for Bennington House, a new condo development on Cambie Street, that I’ve noticed on my daily bus commute to work.

Normally, I watch the storefronts, foliage, and billboards sort of roll along in a multicoloured blur, but this one stood because of how its written. Not what’swritten, exactly, but how.

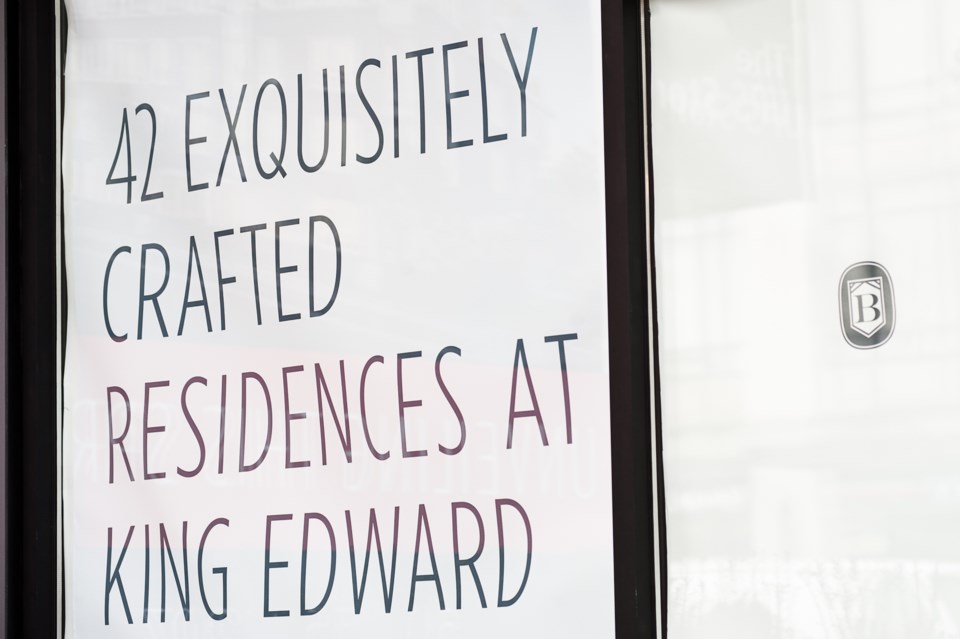

It reads:

42 EXQUISITELY

CRAFTED

RESIDENCES AT

KING EDWARD

STATION

“Crafted”. Given my current professional endeavors, I have “craft” on the brain basically always, so I’m hyperaware of its usage when I encounter it written anywhere. Still, it seemed to me that the word had been ingeniously placed to capture the attention of the sort of people intrigued by craft: craft beer, craft distilleries, the “craft” movement as a whole.

A quick scan of the condo’s website showed that there didn’t seem to be anything particularly artisanal about the building. I’ve certainly never heard of a craft building.What would that look like, exactly? Is it any different from luxury?

In any case, this development appears to be like every other condo development I’ve looked in to lately as a 30-something home hunter.

The usage seems designed to capitalize on the cultural relevance of the word “craft”, propelled largely by the popularity of craft beer, which is now potentially entering the realm of corporate appropriation, like every other influential countercultural movement before it.

The world of craft is definitively cool (for now) and every business that can stake a claim on its frontiers will do so.

Last year, Business in Vancouverreported that developers are drawn to neighbourhoods where craft breweries exist, hoping to capitalize on the trends and potential for growth. It would make sense that they’d use relevant lingo in their marketing.

The Independent, a new tower development at Main and Broadway – down the street from 33 Acres, Brassneck and Main Street Brewing – are selling with the slogan “CRAFTED LIVING AT ITS BEST.” Whatever that means.

And I doubt it’s a coincidence that quite a few people I know have mistaken The Oxford showroom on East Hastings as an advertisement for a new bar.

Craft beer alone isn’t responsible for all of this, of course. The rise in craft beer coincides with the rising popularity of artisanal coffee, farm-to-table restaurants, locally-sourced clothing – craft stuff – and the “indie” culture that immediately preceded it.

All of these movements were borne out of pure and honest creative exploration, the search for solutions, and all have since, to varying degrees, been exposed (or exploited) by big business.

West Elm and West Elm Market’s entire selection seems based around the idea of craft wares. Starbuck’s new baked goods program, La Boulange, is designed to mimic local artisanal bakeries, while Swedish fashion retail giant H&M’s recently launched sustainable collection, Conscious, is an obvious response to people’s shifting buying ethics.

Is this the death knell of craft? Well, perhaps…in a way.

It’s the same way hippie culture was corrupted the minute record companies started capitalizing. The way grunge culture was obliterated the minute Marc Jacobs unveiled his “grunge” collection in 1992.

It happens any time the corporate culture takes hold of a countercultural movement and sells products based around the ideals and aesthetics of it. It kills whatever was pure and honest – whatever was human and heartfelt – about it. This is especially true for craft beer culture, which was borne out of a frustration with corporate-owned macro beer, and corporate culture in general.

“Craft” isn’t about the beer at all – it’s about independence, and exploration of taste, and freedom, and all that. And we’re going to see these ideals injected more and more into advertising, into products, and into the world at large as craft beer culture takes further root in the mainstream.

But it’s not all bad. I’d argue it’s not even remotely bad. It’s a huge success for the craft beer movement, because with corporate buy-in comes marketing muscle and influence that can push the values and aesthetics of craft beer – or any cultural movement – to a much wider audience.

Early craft beer devotees might hate this, but if it means more people drinking craft beer, most brewery business owners should welcome it.

What it means ultimately for craft beer – and craft anything, really – is that the “craft” won’t matter anymore. It’ll all just be beer. Or whatever. Which is fine, because, as I’ve written before, : “craft” doesn’t really mean anything anyway.

Craft is dead; long live craft.