In the days of monopolized beer sales, when just three companies had a stranglehold on the beer market in B.C., only one man was brave — or possibly naïve enough — to thumb his nose at the corporate juggernauts of the day.

That man was “Uncle” Ben Ginter, and while his Prince George-based Tartan Brewing never produced anything that could remotely or conceivably be considered craft beer, his plucky determination and anti-establishment attitude helped embody the spirit of the craft beer revolution that would follow.

Ginter was a Polish immigrant who grew up in rural Manitoba before dropping out of school at 14 to go into business for himself. He started his own construction company and, by the 1960s, had amassed a fortune of close to $30 million by paving the roads and highways of the rapidly expanding B.C. north. In all, his many trucking, construction and paving companies employed more than 9,000 people.

Ginter knew nothing about beer when in 1962, he bought the former Caribou Brewing Co. plant in Prince George for $150,000 which he intended to use as a storage yard for his heavy road construction equipment. The brewery was only five years old, and its brew house was still operational, however. At the time, Prince George had the highest per capita beer consumption in the country — possibly the continent — so after being convinced by a group of local hotel owners, Ginter instead decided to get the brewery back up and running under the name Tartan Brewing. Canadian Breweries, whom he had bought the brewery from, now offered him $150,000 just for the copper brew house so that he wouldn’t brew beer to compete with them. But Ginter’s mind was made up, and the offer, which he took as an insult, only further convinced him.

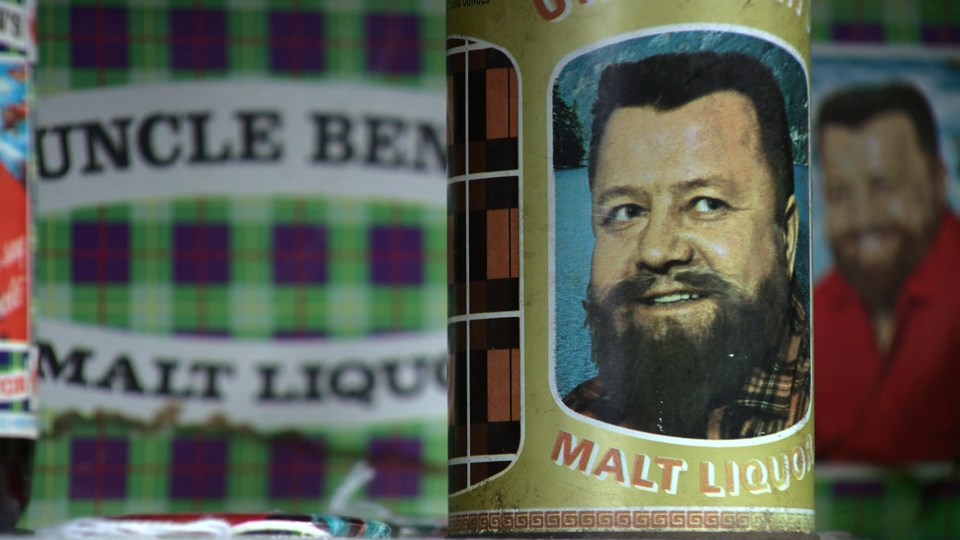

Initially, Tartan produced a series of knock-off beers with names like Budd, Paap’s, High Life and Pil’Can. After a predictable series of cease and desist orders, Ginter rebranded yet again, and this time decided to put himself on the labels — complete with a fake beard — and launch Uncle Ben’s Malt Liquor in 1969. The beer was an instant success thanks to the fact that it was cheap and… well, that’s about it. It was so cheap, the B.C. liquor board actually forced Ginter to increase its price to bring it in line with the likes of Molson, Labatt and Carling O’Keefe. So Ginter started taping a dime to the inside of every 12-pack of beer to refund his loyal customers.

Ever the innovator, Ginter was one of the first Canadian brewers to adopt the beer can and later the pull tab. He was also the first in Canada to offer a refund on empties.

“He was a true maverick,” says Chad Hellenius, assistant curator at Prince George’s Exploration Place Museum and Science Centre. The museum recently recognized Ginter as one of 100 Prince George Icons. “You have to look at him as a pioneer of viral marketing campaigns.”

Ginter hired Austrian-born Eugene Zarek to be his brew master and by many accounts, the quality of the beer initially ranged from merely terrible to borderline undrinkable.

“It was improperly aged,” according to Hellenius. “It was described at the time as being ‘green and chewy.’”

The quality did improve, however, and by 1977, beer expert Michael Weiner would proclaim that Uncle Ben’s Malt Liquor was “almost perfect” in his book, The Taster’s Guide to Beer.

Ginter was every bit the rough and tumble frontiersman he depicted on his beer labels. Big and barrel-chested, he was a gruff self-made man, usually wearing blue jeans and a red flannel shirt instead of a businessman’s three-piece suit. He worked tirelessly to build his empire, and he expected everyone around him to do the same, which resulted in predictable labour conflicts.

“Ginter is a work addict,” wrote Allan Fotheringham in Maclean’s magazine in 1968. “Just as hooked as the dope addict, the booze addict, perhaps just as unhappy and guilty about it.”

For close to 20 years, Tartan Brewing was a thorn in the side of the Big Three breweries: Labatt, Molson and Canadian Breweries (later renamed Carling O’Keefe). In the late ’60s and ’70s, he sought to expand his empire across the country, opening breweries in Alberta and Manitoba, while plans for breweries in Ontario and Newfoundland proved to be costly failures. The Big Three — and the provincial governments that supported them — fought him every step of the way.

“He was dangerous,” says Hellenius. “He was sticking that big middle finger up at them because he played by his own rules.”

The constant opposition caused him stress, and paranoia. Ginter famously accused his competitors of hiring actors who would order Tartan beer and then loudly complain to the bartender about how bad it was and dramatically pour it out, only to ask for a “real” beer by one of the Big Three instead.

Eventually, the ill-advised expansion resulted in Ginter overextending himself. In a last ditch effort to raise funds, he offered public shares in his company in return for bottle caps, according to Allen Winn Sneath in his book, Brewed in Canada. Two hundred caps could be traded in for a block of 10 shares valued at $200. Despite the incredible value being offered, the promotion failed to increase sales.

By 1978, Ginter was bankrupt and much to the joy of the Big Three breweries, Uncle Ben’s was done. Ginter died of a heart attack in 1982, his fortune gone.

Nothing remains of Ginter’s empire, not even his once opulent, ostentatious Prince George mansion. According to Fotheringham, it featured preserved butterflies mounted in the ceiling, Japanese silk wallpaper in the bedroom, a royal purple velvet headboard, stuffed woodpeckers and squirrels over the fireplace and the clock in the simulated-leather cowboy boot, a 20-by-40-foot indoor pool, backed by an artificial waterfall that, “at the touch of a button sends water cascading over the plaster elves and their fishing poles.” In the den, beneath the velvet painting of the fighting stallions is the bar, covered in the soft skin of unborn calves.

The original Tartan Brewery in Prince George is still in operation, however, albeit under a different name and ownership: Pacific Western Brewing, home of Cariboo lager.

“Although he was only a player for 15 years,” writes Sneath, “his unorthodox approach to business reserves him a permanent place in Canada’s modern brewing history.”

He may have been ahead of his time, but Ben Ginter’s anti-establishment attitude and dissatisfaction with the status quo would become hallmarks of the craft beer revolution to come.