In an overgrown cemetery on the near-deserted Exploits Island, in Notre Dame Bay, is a horizontal gravestone.

Much of the engraving is illegible, worn away by the elements, but I could pick out the words “John Peyton” and “John Peyton Jr.”

“That was the Peytons, father and son,” said our guide. Then he added, matter-of-factly, “They were Indian killers.

This grave is a page in one of the most tragic stories in Newfoundland, indeed in North American, history: the ritual annihilation of the colony’s native people, the Beothuk, who were hunted to near-extinction by the European colonists. What murder couldn’t complete, exposure to European diseases and starvation, as Western encroachment pushed them further from their traditional food sources, did.

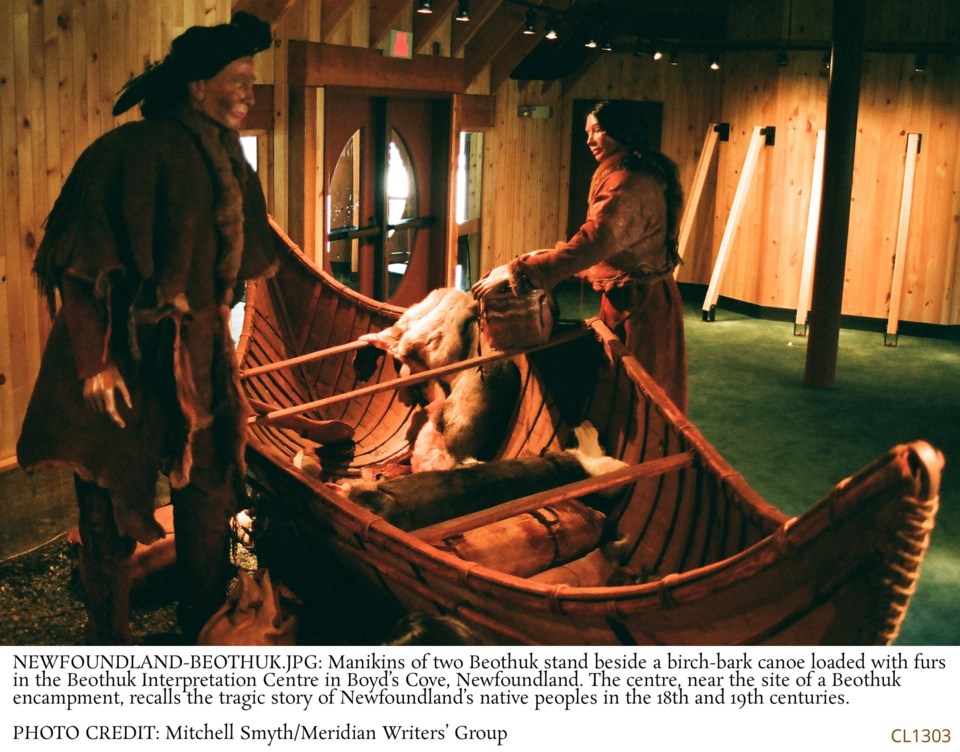

Some of the story can be found in the Beothuk Interpretation Centre at Boyd’s Cove and the Mary March Provincial Museum in Grand Falls-Windsor, respectively north and west of Gander in central Newfoundland.

Mary March was the name John Peyton Jr. gave to Demasduwit, 23, the wife of Chief Nonosbawsut, when he captured her after killing her husband in March 1819 (hence her new name). She was one of the last of the Beothuks; by the time she was taken there were only 30 or so still alive.

One of them was Shawnadithit (also called Nancy April), who became a servant, unpaid of course, of the Peytons. By 1825 it was clear that she was the sole survivor of her race. She died in St. John’s in 1829 and the Beothuk were extinct.

The interpretive centre at Boyd’s Cove is built near a Beothuk encampment that was excavated in the 1980s, yielding hundreds of artifacts and providing clues on how the native people lived. But the tale it and the Mary March museum tell is incomplete, for by the time anyone began to care about the Boethuks it was too late.

We do know, however, that they were the original “Red Indians” of North America, so-called because they painted their bodies with red ochre.

“The pejorative ‘redskin’ derives from the first white encounters with the Beothuks at the end of the 15th century,” writes historian Pierre Berton in My Country: the Remarkable Past.

The Peytons’ hatred of the Beothuk stemmed at least in part from their repeated pilfering of Peyton fishing gear, but killing natives was also a sport to the early colonists.

“Men set out on shooting parties as they would for deer or wolves,” Berton writes, and quotes a British Army lieutenant as saying in 1768: “He that has shot one Indian values himself more upon the fact than had he overcome a bear or a wolf.”

The sport continued even after it became illegal in 1789. “No one was ever punished for killing a Red Indian,” says Berton.

One of the bloodiest of the hunters was John Peyton, matched, almost, by his son. Much of their hunting was done on Exploits Island where, before her capture, Shawnadithit had spent her days, little dreaming she would soon be the last of the Beothuks.

For more information, visitheritage.nf.ca. More stories at culturelocker.com.