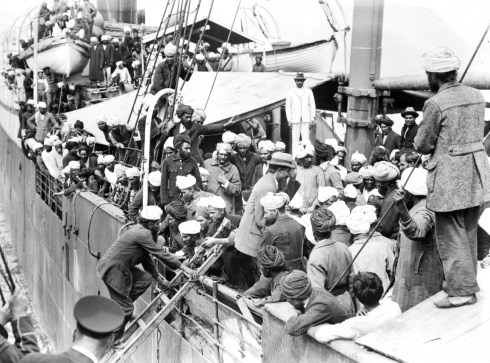

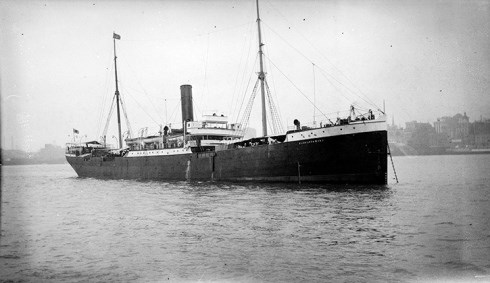

As the Vancouver shoreline became a thin line of reality in the early light of May 23, 1914, the 376 South Asian passengers aboard the Komagata Maru readied themselves to be received.

Bags packed, some donned their finest western suits while others smoothed the wrinkles out of old military uniforms with pride.

Jubilant smiles creased their sea-weary faces; they had just sailed for two months across the Pacific to a better life in Canada, and, within a few hours, it was set to begin.

But those men would be labelled by Canadian politicians as unwanted and by early history as naive. Most of the men would never be allowed off the boat.

Now known as one of the darkest days in Canadian history, the Komagata Maru’s arrival was a spectacle for Vancouverites. Pleasure craft flocked to the harbour to inspect and ridicule the “Hindoo” invaders while the passengers’ resources and morale dwindled. Conditions on board rapidly became dire.

Only 20 passengers who already had resident status or the requisite funds were allowed to disembark and join the small Sikh community that had been growing in Kitsilano since 1897.

While their fates could be considered lucky compared to the more than 350 who were forced to languish in Burrard Inlet for two months before being escorted away by gunboat (onlookers expressed disappointment that the ship wasn’t “blown up” upon departure), or the 19 “suspected seditionists” who would be killed in a shootout with British authorities upon return to India, the landed immigrants faced an uncertain future spent fighting for every basic right.

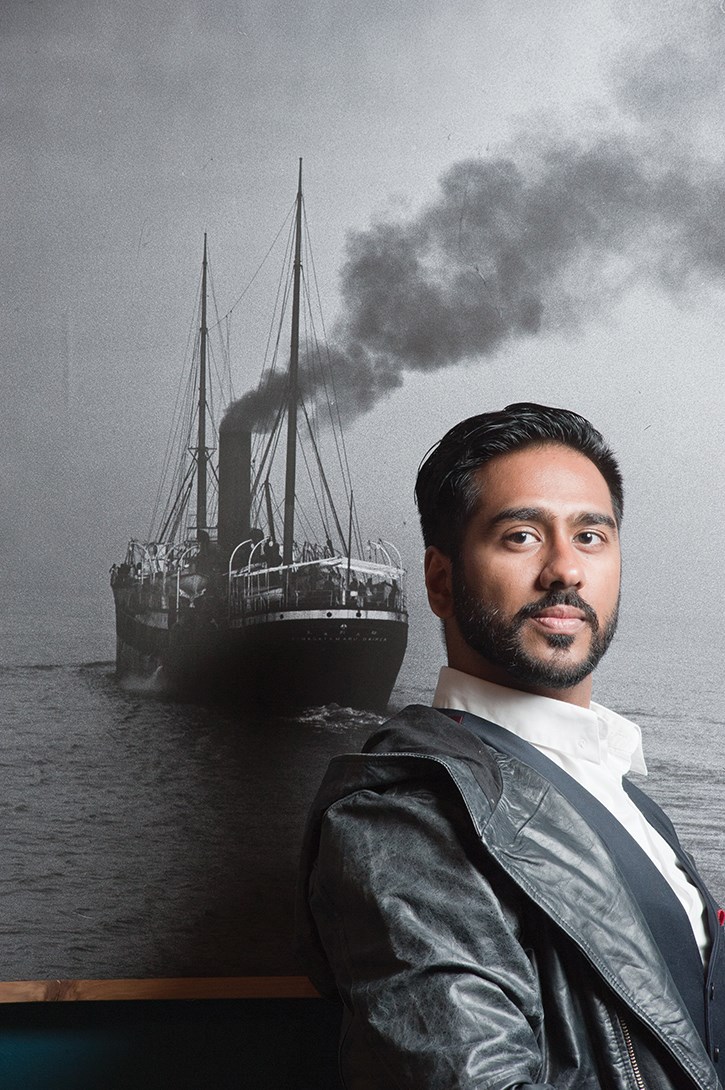

That they and their descendants were eventually successful is part of what makes the Komagata Maru more than just a South Asian story, says Komagata Maru 1914-2014: Generations, Geographies and Echoes project manager Naveen Girn.

Girn, 34, grew up in Vancouver unaware of the battle that had raged so many decades earlier. Only one day of the curriculum at his high school was dedicated to minority histories: the Chinese head tax, Japanese internment and the Komagata Maru.

It wasn’t until a history class at SFU that he learned the true extent of this South Asian legacy, and he is among a large number of Indo-Canadians interested in expanding what we know about its impact.

There was little formal record of early South Asian life in Canada, so Girn began tracking down and preserving what little remained. As he researched, the ridges and whorls of the South Asian fingerprint embedded in present-day society rose very clearly into view.

“The Komagata Maru links so strongly to other narratives,” he says softly over the phone. “Stories of female immigration, of trying to get the right to vote, of citizenship rights or labour histories, of arts and culture organizations. It all stems from this story.”

Around the time of WWI, Vancouver was a city trying to define itself. At the political level, BC was being cordoned off as a white man’s province, but at the grassroots level, years before multiculturalism became a Pierre Trudeau buzzword, there was an established practice of Chinese, Japanese, South Asian and First Nations building communities together.

Girn explains with awe how, in Punjabi, there is a word for First Nations that exists only in the Vancouver vernacular and is based around the term for cousin, born out of the two groups working and living side by side.

Girn also recalls an article in the Hindustanee at the turn of the last century that stated the best restaurants in Vancouver were Chinese restaurants, because, unlike the ones in Gastown, they didn’t discriminate against South Asian patrons.

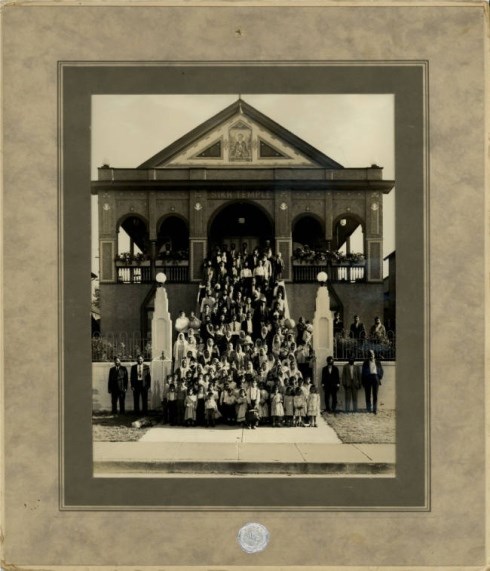

Vancouver was also the site of North America’s first Sikh gurdwara, or temple, located at Burrard and 2nd and surrounded by South Asian businesses. The first Sikh wedding in North America was in fact performed there between Munsha Singh Sheanh, a Punjabi pioneer, and Annie Wright, his English tutor.

But most of what historians could discern of this vibrant, wholly masculine community (there were only two landed South Asian women documented between 1898 and 1914) was gleaned from dry government surveillance reports, land documents and archival newspaper clippings.

“There is this large silence,” says Girn. “Trying to find South Asian stories in libraries or university archives, there’s not much there.”

Hugh Johnston, the professor who taught Girn, was one of the first historians to recognize the importance of the Komagata Maru.

Revised for the centenary of the Komagata Maru incident, the opening pages of his book The Voyage of the Komagata Maru: The Sikh Challenge to Canada’s Colour Bar explain how Punjabi immigrants “received far more attention and generated far more public anxiety than their numbers warranted.”

Their presence in the west was the subject of vicious objection, from local media to the highest levels of government.

The anti-Asian riots of 1907, sparked by the imminent arrival of a CPR ship carrying 901 Punjabi immigrants, prompted the creation of the discriminatory continuous passage law that would ultimately block the passengers of the Komagata Maru.

“The rioters didn’t go after Punjabis because there were practically none in town,” Johnston says of the clash that would leave considerable damage to Chinese and Japanese property, “but that was the background. That riot impressed [Prime Minister Wilfrid] Laurier particularly. He thought it was going to give the West Coast a bad reputation and turn people and money away.”

The Canadian government solved the immigration problem by halting it entirely. “After 1908, no one was allowed in,” Johnston explains. That decision was pivotal for the Indian immigrants who had previously enjoyed easy entry, as members of the community on both sides of the ocean immediately began working towards reversing it.

It was one of the motivating factors for Gurdit Singh. By chartering the Komagata Maru, the wealthy Punjabi was attempting to set the precedent that British citizens were free to travel anywhere in the Commonwealth.

“Simply put,” says Johnston, “they wanted to come through the front door.”

It was an ambition he categorizes as dangerously misinformed, but the voyage still stands as the most “dramatic challenge to Canadian immigration policy ever mounted by a disadvantaged immigrant group.”

The facts remain the same, but Johnston emphasizes the significance of the challenge more now than he did in his first edition of Voyage, written 35 years ago.

“They kept [at it] by petition, by sending eminent people to Ottawa on their behalf; they didn’t ever quit trying to get a full place here. And it took a long, long time. But all the way through you can see the community’s effort.”

Within minutes the gifted storyteller has laid out the impact of the Komagata Maru: By the 1920s, South Asians had succeeded in bringing their wives over; they achieved amnesty for illegal immigrants, who made up nearly 40 per cent of the population, in 1939; the right to vote was granted in 1947; then, in 1951, came the first quota for immigration.

Perhaps the biggest impact can be seen in the current size of BC’s Indo-Canadian population – 274,065 as of 2011.

“It was extremely small when I started this research,” Johnston says. “When I came to Vancouver in 1968, there couldn’t have been more than 12,000 in BC. History is about the winners; about people who are dominant. At the time of the Komagata Maru, the tiny South Asian population lost. But they only lost temporarily. Over time they have become winners in Canada, and now we hear their history.”

But it didn’t come soon enough for some.

Vancouver resident Sukhi Ghuman’s great-grandfather, Harnam Singh Sohi, was one of the passengers on board the Komagata Maru. After being sent back to India, his dream for his family was eventually realized by the marriage of his daughter to a Canadian, but he refused to ever return.

As a student, Ghuman, 34, doesn’t remember learning about the Komagata Maru or this chapter of her family’s history. She stumbled upon it by chance when a Punjabi professor shared a poem he had written about the incident. She rushed to ask her father about it, and then learned about her great-grandfather’s ordeal.

“I was really shocked and disappointed,” she says of the belated discovery. “Shocked at the fact that this was such a historical moment not only for South Asians living in Canada, but for Canadian history, and it wasn’t something that came up in school. And I was really disappointed because soon after I found out about the incident and realized that I had a family connection, my grandma passed away. So I didn’t have the opportunity to talk to her about it.”

Meanwhile Girn has slowly been gaining the trust of other community elders, sitting down with them in their homes and going through their private archives. Much of what he has gathered will be on display in honour of the centenary.

“The anniversary is a great opportunity to increase awareness and education about this historical moment, because the Komagata Maru needs to be woven into how we tell the story of Canada. It’s a very genuine moment that speaks to the way people experienced life in Canada.”

In the last decade, the city, province, and federal governments have apologized for the episode. The federal government’s 2008 apology, delivered by Prime Minister Stephen Harper in a Surrey park, however, was largely dismissed as too informal.

And the wound was reopened earlier this year when a man was seen urinating on the Komagata Maru memorial in Coal Harbour. The man, a Downtown Eastside resident with a history of mental illness, apologized for his actions, but comments on message boards revealed a discouraging disconnect between many Canadians and the story of those South Asian pioneers.

So all eyes will again be on Vancouver over the next few weeks to see how the city responds to its historical responsibility.

“From start to finish it is a sad story, but it is the story of my life,” writes Gurdit Singh in the The Voyage of the Komagata Maru Or, India’s Slavery Abroad. “If my story paves the way for repetition of any such single inequity being impossible, on any one in the future, I shall die in happiness to know that I had done my duty.”

*******

More than 16 exhibits and events have been curated to honour the 100th anniversary of the Komagata Maru. Some highlights include:

Komagata Maru: Challenging Injustice

An engaging narrative from the point of view of the 376 men aboard the ship. On until June 8 at the Vancouver Maritime Museum.

Ruptures in Arrival: Art in the Wake of the Komagata Maru

A cross-section of visual art related to this history, alongside art that addresses more recent histories of mass migration from Asia to Canada’s West Coast. On until June 15 at the Surrey Art Gallery.

Echoes of the Komagata Maru

The social story of the Komagata Maru, personalized through image, sound and video. On until July 12 at the Surrey Museum.

Unmoored: Vancouver’s Voyage of the Komagata Maru

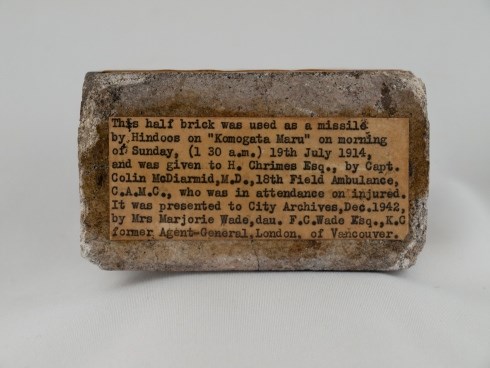

Opening May 21, it is centred around the only surviving artifact from the Komagata Maru – a brick known as the “Hindoo Missile”, hurled during a midnight boat raid. This exhibition also remaps Vancouver in the context of its histories of racial discrimination, intercultural dialogue and political revolution to ensure the Komagata Maru is still felt today onto the streets – and landscapes – of the city. On until July 31 at the Museum of Vancouver.

Interactive events exploring the Komagata Maru are scheduled this month at the above locations (and SFU) and through the Khalsa Diwan Society at the Ross Street Temple.

The centenary celebrations also include a free event at Harbour Green Park in Coal Harbour on May 23 from 12:30-3pm. SFU library will unveil its Komagata Maru collection the same day.