When city council voted Tuesday to knock down the Georgia and Dunsmuir viaducts, it also voted to right a wrong of Vancouver’s past and commemorate the loss of the black community’s roots in Strathcona.

But what that commemoration looks like is a work in progress, although some of the people who spoke to council over two days of hearings made it clear that arts, culture, a memorial and housing should be in the mix to pay tribute to what was known as Hogan’s Alley.

“This is your chance to not only acknowledge past dislocation and exclusion but to see to it that the black community that was displaced and the subsequent generations who have been impacted by that loss are thoughtfully consulted with the purpose of re-establishing a place for Vancouver’s black community,” said Stephanie Allen, an urban studies master’s student at Simon Fraser University who wrote about the history of Hogan’s Alley for a research paper.

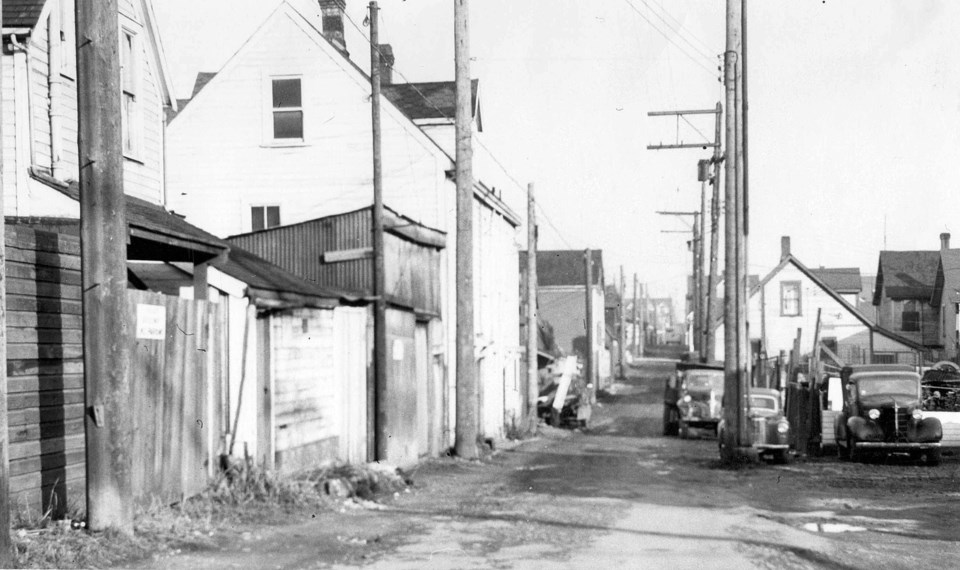

Hogan’s Alley, which was centred between Prior and Union and Main and Jackson, was home to much of Vancouver’s black community in the first half of the 1900s but it was destroyed when the Georgia and Dunsmuir viaducts were built in the early 1970s.

In Allen’s presentation to city council, she quoted the “Vancouver development study” published in 1957 that was meant to guide urban renewal. The study mapped decaying areas in Vancouver and said options were to clear them out or restore and conserve them.

“In the study, the area occupied by the black community was identified as being a first priority for removal due to the severity of blight,” she said, quoting from a page in the document that acknowledged displacement “is bound to create special problems for these minority groups.”

Allen argued the reason Hogan’s Alley was considered a blight on Vancouver was because the city government of the day did nothing to fix up the streets, buildings or parks.

Writer Wayde Compton, a member of the Hogan’s Alley Memorial Project, said proper commemoration of the black community’s roots is an opportunity to send a message to Vancouver’s 20,000-plus citizens of African descent “that their history in the city is remembered and valued and honoured.”

“A sacrifice was made for this mistake, and it was us,” Compton said of the addition of the viaducts. “Whether it’s a memorial, or in the form of a cultural centre — or whatever it is — [there has to be] some acknowledgement that this was an area that was significant to the black community.”

Randy Clark, who spoke to council on behalf of the United Black Canadian Community Association, said he supported the removal of the viaducts but emphasized the city must “celebrate” the history of Hogan’s Alley as it proceeds with redevelopment of the viaduct lands.

Clark was a resident of Hogan’s Alley in the 1960s and lived with his mother and five siblings at 230 Union St. His grandparents’ restaurant, Vie’s Chicken and Steak House, was across the street. (The location was once home to a shrine to musician Jimi Hendrix, whose grandparents lived on East Pender and East Georgia.) Clark, a retired Vancouver school principal, is a direct descendant of the first black settlers to Saltspring Island and Victoria, dating back to 1858.

“From all accounts shared with me, during the 1930s and 1940s, this was a great community to grow up in,” he said, naming off a list of black families, including the Collins, the Holmes, the Howards, the Kings and the Woods. He said families watched out for each other and he noted the Fountain Chapel church at Jackson and Prior streets was a popular meeting spot. “Stories were shared, experiences were common, friendships abounded and there was connectedness — community.”

Talk of building a freeway in the 1960s and the eventual construction of the viaducts destroyed the community, said Clark, echoing Allen’s argument that the city government failed to invest in Hogan’s Alley.

“By 1965, when I arrived, the black community — for the most part — didn’t exist, it wasn’t the same,” he said. “I refer to the previous 10 years as a system of systemic profiling of our people and our neighbourhood. Structures were left to decay, homes were either sold or abandoned and only after long periods of time were they removed. Nothing new was built.”

Council is already on record via the Downtown Eastside community plan that it will address restorative justice issues and the need for social and cultural facilities – and commemoration – of the black community displaced by the viaducts.

But with the viaducts coming down, the opportunity to do something now is real. Mayor Gregor Robertson and some councillors quizzed Allen and others about suggestions to commemorate Hogan’s Alley.

“Whether it’s arts, culture or affordable housing — things for immigrant communities who are newly settling to this city, I think there’s a lot of opportunity for that dialogue to trace quite a few different paths,” Allen told Coun. Elizabeth Ball, who said she was assured by city staff that renewal plans for the viaducts lands “would be addressing the issues in the neighbourhood” related to the history of the black community in Strathcona.

When the viaducts are demolished, it will free up two city-owned blocks that straddle Main Street. The city staff report that recommended knocking down the elevated roadways suggested up to 300 units of “affordable housing” could be built on the property.

Although he didn’t promise affordable housing would be a component of commemorating the black community, Robertson told Allen he was “hopeful there’s a really robust community effort that’s part of this in reshaping” what was lost in Strathcona.

@Howellings