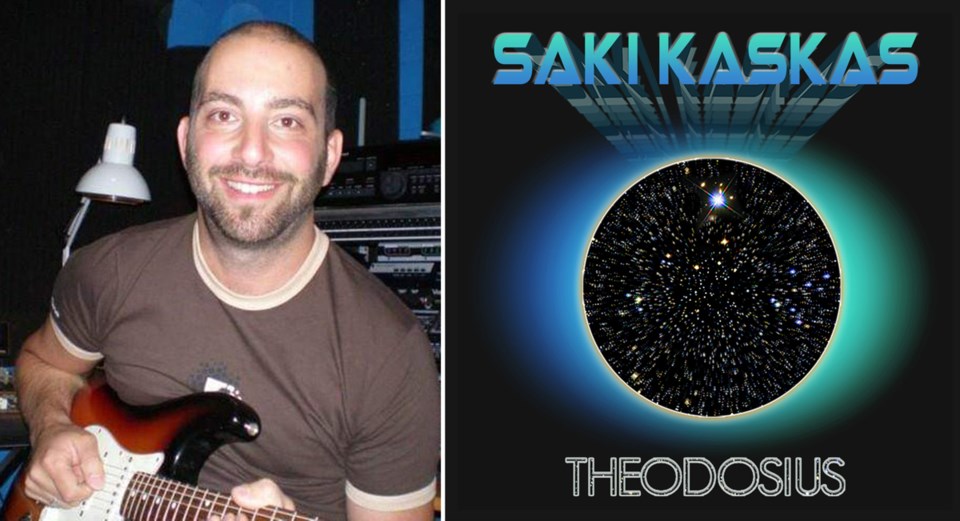

His full name was Theodosius Kaskamanidis, but most knew him as Saki Kaskas.

Everyone knew Kaskas for his unfailingly positive attitude and encyclopedic knowledge of capital cities.

Millions knew Kaskas as the musician responsible for soundtracks that accompany some of the most iconic video game franchises ever released.

The side of Kaskas no one knew became clear Nov. 16, 2016, when his lifeless body was discovered by his ex-girlfriend, police and his sister.

Kaskas had died of a fentanyl overdose five days earlier, on Remembrance Day, in his Gastown apartment.

It was only after reading his private journals and the coroner’s report that his loved ones learned Kaskas had battled heroin addiction for a decade.

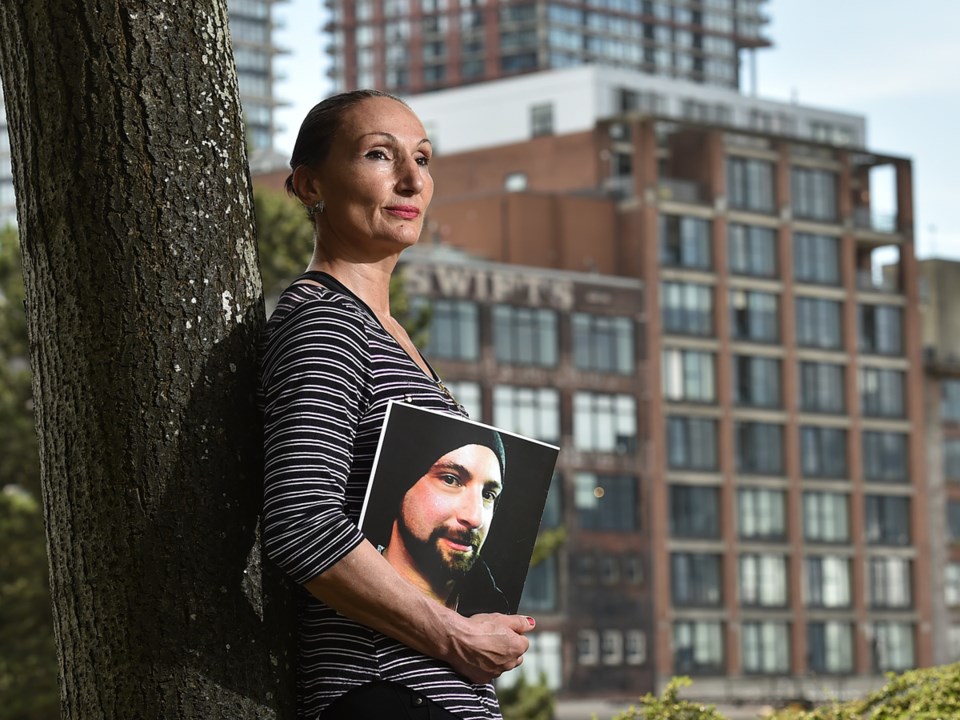

“There were signs, there were red flags. Today, I know that,” his sister, Sia Kaskamanidis, told the Courier. “The nodding off especially. I didn’t even know what that was about. When I asked him, he said it was because he was working so hard all night. I believed him.”

Kaskas was working on a solo album more than a half decade in the making at the time of his death. He quit his lucrative job in the tech sector, sold his condo and moved downtown to devote, at most, two years to creating what would be his first album after decades of making music for and with others.

The album was totally in flux at the time of Kaskas’s death. Some songs were done, others weren’t even close. It needed other musicians to round out the sound, finish the lyrics and take care of mixing and mastering.

That process comes full circle June 28 at the ANZA Club, when Kaskas’s album Theodosius will be released.

It took 22 musicians from across the world to finish what the 45-year-old started.

Former co-worker and longtime friend, Jeff van Dyck, has been the catalyst behind all those moving parts. The pair had known each other since the early 1990s, first as bandmates and then as coworkers with Electronic Arts (EA).

Finishing the album was a process that took almost three years and began in the months before Kaskas’s death. Now residing in Australia, van Dyck connected with the Courier via email in early June, just days after completing the album.

Van Dyck uses words such as “relieved” and “bittersweet” when describing the first listen.

The term “brilliant functioning heroin addict” also enters the conversation, both with van Dyck and Kaskamanidis.

“I suppose in retrospect I can start to see the signs, but I was pretty clueless and had no idea what he was up to,” van Dyck said. “I had attributed his lack of finishing his album to being burned out on it, which can happen to anyone who works hard on something for a long time.”

Musical upbringing

The Kaskamanidis family lived in Dunbar, and all four kids went to Prince of Wales secondary. Kaskas was drawn to music in his early teens — Led Zeppelin and the Who were the bands that lit the initial spark.

“He got a guitar in Grade 8 and everyday he would practice his scales,” Kaskamanidis said. “His buddies would come over and say ‘Hey let’s go out and have some fun.’ No, he would just practice.”

Kaskas’s time at EA began in the early 1990s. He met van Dyck around the same time, and the two played in bands before they ended up working together at EA.

Kaskas was surrounded by musical talent and excelled as a sound engineer and composer. The work hours were insufferably long in those early days of EA, but Kaskas’s output can be heard on video game titles such as The Need for Speed, Mass Effect 2 and several of the NHL Hockey games released in the mid to late ’90s. Kaskas later went to work for the Vancouver tech firm United Front Games, and his compositions have been aired on TV and radio.

One of his jingles was used by Oprah Winfrey, for which the royalty cheques keep rolling in to this day.

Simply put, Kaskas’s music has been heard by tens of millions of people the world over.

As satisfying as that was, Kaskas spent his entire adult life making music for others rather than what he heard inside his head.

That changed in 2014.

Sudden shift

Kaskas left the working world in 2014 at the age of 42 and opted to live off savings and royalties.

He bought a condo not far from the Downtown Eastside and equipped it with a $50,000 home studio.

Kaskamanidis describes her dad as being “crushed” by the seemingly sudden shift. The family matriarch was supportive and wanted to see her son realize his dream of making an album by himself, for himself.

Kaskas told his family he would give himself two years to finish the album and that he’d re-enter the workforce once it was done.

“I was little bit concerned. I thought ‘Hmm… that’s weird,’ but he did reassure us,” Kaskamanidis recalled. “I was very supportive of his music. I felt him hurting all these years. He was struggling working in a corporate environment. I saw the artist in him, so I said ‘OK, finally you did it. That’s great.’ I was naïve.”

Van Dyck visited Kaskas in his home studio a month before his death for what was supposed to be a preview of the completed album. Being a fellow musician, friend and trusted ear, van Dyck offered some advice: more live drums, less drum machines and an emphasis on vocals — up until that point the 12-track album was all instrumental.

Kaskas agreed but couldn’t figure out how to get there. Van Dyck planned to come to Vancouver at some point the following year to help his friend realize the album’s completion.

It was to be the first time the pair would collaborate on original music in roughly 25 years.

Kaskamanidis reflects on her brother’s death as an accidental tragedy, but one clouded by shame and guarded secrecy. The coroner who attended Kaskas’s condo after his death found rehab pamphlets everywhere.

Kaskamanidis later found her brother’s private journals, in which he wrote about the nightmarish withdrawals experienced by a heroin user.

One journal entry suggested there are two types of people in this world: those who try drugs and don’t go any further because they love their lives, and others who try drugs and keep using them because of self-loathing.

Kaskamanidis isn’t sure if either holds true as it relates to her brother’s fate. Kaskas had social anxiety but was described by both his sister and van Dyck as an outgoing, gregarious person. He loved travelling, cycling, reading about the world and watching sports with his pals.

“It’s a big mystery. We don’t why he was using drugs or why he used them for so long,” Kaskamanidis said. “He said he was using heroin not to get high, but to relieve pain or to feel normal.”

Catharsis and celebration

Theodosius was finished in early June after van Dyck tracked down EA alumni, Kaskas’s friends and anyone else who could complete the vision.

Only two of the 14 songs were finished at the time of Kaskas’s death. Though the rest were in varying stages of completion, van Dyck had the benefit of knowing Kaskas’s ear and taste such that becoming a makeshift producer wasn’t overly daunting or difficult.

The end result is a complete hybrid of an album that’s all over the map: heavy metal, industrial, jazz, disco and funk.

The end game is catharsis and celebration for van Dyck and the musicians involved.

Kaskamanidis’s head is in a slightly different place. She was hesitant to contact the Courier about her brother’s album. She had a hard time reconciling the same stigma that ultimately consumed her brother — saying nothing, rather than saying everything.

There was a time when Kaskamanidis thought everyone living in the Downtown Eastside was there by choice. She also believed addiction was a choice.

“I used to be ignorant about addiction,” Kaskamanidis said. “My brother’s overdose opened my heart to the whys and hows of an addict. I have changed from an apathetic, judgemental person to a sympathetic and caring one.”’

Those attending the Theodosius album release show will be encouraged to donate to the Providence Crosstown Clinic at St. Paul’s Hospital. Crosstown is the only clinic in North America to offer medical-grade heroin (diacetylmorphine) and the legal analgesic hydromorphone within a supervised clinical setting to chronic substance use patients. A link to donate online is HERE.

The Theodosius album release party is scheduled for 7 p.m. at the ANZA Club on June 28.

@JohnKurucz