A member of the Vancouver Police Board says overdose death statistics do not represent the full magnitude of the opioid crisis because many survivors of an overdose end up in hospital to be treated for brain damage and other serious health conditions.

Sherri Magee, an oncology researcher, made the point at a Jan. 18 board meeting after hearing an update on the overdose death crisis from Insp. Bill Spearn of the Vancouver Police Department’s major crime section.

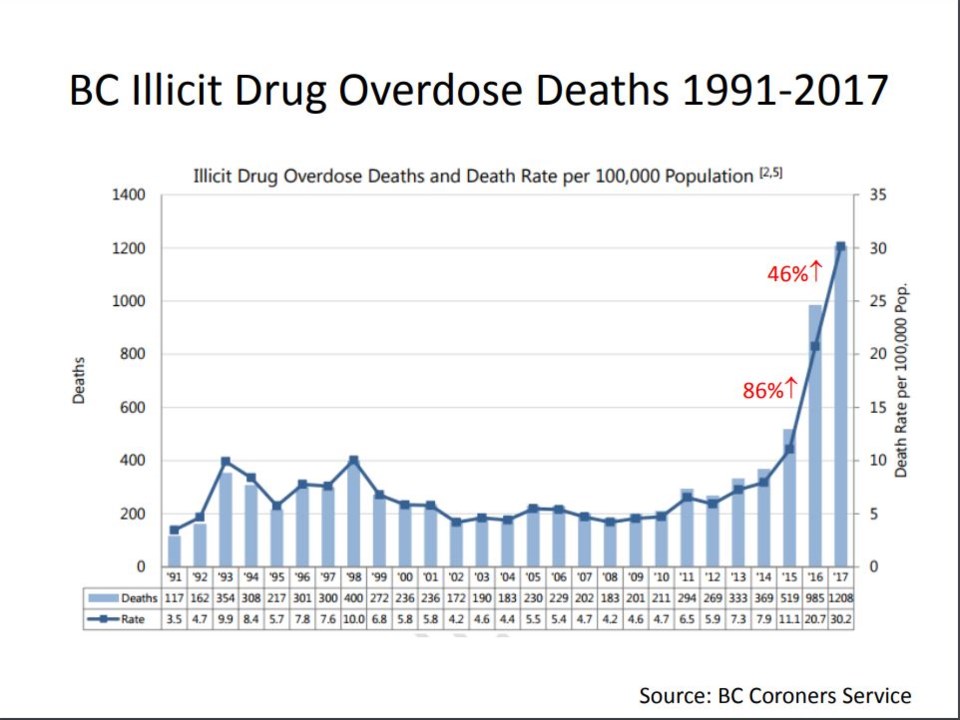

“This is the most common graph that we see,” said Magee, pointing to a screen display from Spearn’s presentation showing overdose death statistics. “But my medical colleagues will say we need to start looking at some other data around morbidity. You see — especially from multiple overdose cases — that there’s permanent brain damage, there’s cardiac damage, there’s respiratory, there’s long-term chronic physical changes.”

Added Magee: “It’s staggering what’s happening to these people.”

Spearn told Magee that he is not aware of such data being readily available but has heard from emergency room doctors that intensive care units are flooded with overdose victims in serious condition and “waiting for their organs to be harvested.”

“We hear about the deaths, we don’t hear about the people who are revived and essentially brain dead and then brought to [the intensive care units] and remain there,” Spearn said. “This data absolutely does not reflect that.”

More than 300 people in Vancouver are suspected of dying of a drug overdose last year, according to police data collected by the City of Vancouver. Total deaths for the province in the first 10 months of 2017 were more than 1,200. The death toll will be updated this week when the BC Coroners Service releases new data.

Dr. Adam Peets, a clinical associate professor in St. Paul’s Hospital’s intensive care unit, said the number of overdose victims in the intensive care unit can range from five per cent to 20 per cent, depending on the week.

“It’s a significant number if you look at all the different causes that could lead to someone being admitted to an ICU,” Peets said. “It’s not a small number.”

He said about 20 per cent of patients in the ICU survive whatever injury or illness had them admitted to hospital. But to his knowledge, Peets said, the province’s health care system doesn’t track “six months, or a year out how these individuals are doing cognitively.”

He agreed with Magee that such information about patients who survive an overdose would be helpful in understanding the magnitude of the opioid crisis.

“It puts a lot of stress not only on the individual who has suffered that damage, but on their family members and loved ones, and also on the system that has to support them with significant disabilities for the rest of their lives,” said Peets, noting the ICU medical team at St. Paul’s has been affected by the crisis. “It sounds kind of selfish — in the sense that we’re worried about ourselves — but that’s not the case. Obviously, we take care of the patients first. But afterwards, everybody needs to decompress because it’s a lot of very — for the lack of a better term — depressing situations that they find themselves in. It takes a toll on the team, too.”

The team has cared for overdose patients who later died and had organs donated, to others who made a successful recovery, only to end up in the ICU “again and again and again,” Peets said.

Andy Watson, a spokesperson for the coroners service, said if a person survives an overdose — but dies months later — the coroners service would still classify the death as an illicit drug overdose, Watson said in an email to the Courier.

“In terms of those who live or are living still, that would be up to the health authorities to capture – we only investigate sudden and unexpected deaths,” he said. “But once someone is deceased, that comes to us. If it’s determined it is a natural death unrelated to opioids we would not investigate. But anything related to illicit drug deaths, we do investigate.”

Police Chief Adam Palmer and Mayor Gregor Robertson, who doubles as chairperson of the police board, told reporters after the Jan. 18 meeting that Magee’s point about overdose survivors highlights the seriousness of the crisis.

“They may not be captured in the stats, but that is a longer term issue [and] drain on the health care system and really another side of that tragedy that probably hasn’t been reported on that much,” Palmer said. “It’s an interesting dynamic to probably shed some light on.”

Robertson: “The impacts beyond just the deceased are immense — from the mental health impacts to first responders and the trauma for family and friends.”