Originally published Feb. 4, 2011

The sun sets in Clark Park and the last of the day's dog walkers, frolicking children and families of the surrounding East Side community are winding up their Saturday afternoon visit.

Tracy Carroll walks briskly past the entrance. "To this day I don't like going near the park," says Carroll. Now in her 40s, she attended school in the area as a child. But her fear isn't from the visitors today — she can't forget those who occupied it years ago and are forever associated with the park in her mind. The second oldest park in the city--located at East 14th Avenue and Commercial Drive — is still remembered by many as a hangout for one of the most notorious periods in the history of Vancouver gangs.

The only visual nod to the area's past stands nearby at Clark Drive and East Sixth.

The iconic "Van-East" cross that was popular graffiti of Vancouver's East Side years ago — to some simply an emblem of community pride and to others often recognized with area gangs —now stands nearby as an installation by artist Ken Lum. And where a thug in a mack jacket swinging a chain might have greeted those who weren't from the neighbourhood, now the white LED-lit 20-metre sign innocuously welcomes Vancouverites entering the East Side.

But the presence of gangs in the city goes back over 100 years with the first newspaper mention of a gang appearing in the Nov. 23, 1909 edition of the Province. The story details that police had identified and apprehended a "gang" following a series of house burglaries in Mount Pleasant, reporting a "Mrs. Keddy" at 699 Cambie St. was "robbed of furs, silverware and $20 in cash" from her home.

In the 1920s and '30s Vancouver's first gangs were largely orphaned street kids and dropouts who travelled in packs. With names like the Cordova and Homer Street gangs, they hung out on street corners, harassing passersby and engaging in store robberies, automobile theft, arson and vandalism.

The gangs of the 1940s were notoriously territorial and violent, such as the extravagantly dressed zoot suit gangs who in addition to robberies regularly sparked confrontations that broke into street riots at downtown dance halls with merchant marines and soldiers on leave.

In the 1950s, gangs such as the Alma Dukes based at Broadway and Alma marked the switchblade and greaser era. Automobiles gave the gangs wider access to the city and inter-gang rumbles and street racing were termed "Friday Night Madness" by the public and viewed with the same trepidation and rise in police calls that "Welfare Wednesday" does today.

A pattern began as daunted citizens blamed each generation of gangs of being more dangerous than the last. The gangs tended to be more violent delinquents than organized criminals, and may seem quaint or anachronistic compared to the gangs police deal with today. It all changed with the notorious era of the Park Gangs in the 1960s. Made up from as many as a dozen gangs identified by the city parks that served as their turf, they would be the city's first modern gangs that evolved into a severe criminal threat, some helping characterize the city's East Side as a legendary tough neighbourhood for the next 30 years.

"As kids we'd walk from school down 33rd [Avenue] heading to the pool where my father worked, and I'd see the Riley Park gang guys. They had bats and chains--really rough guys, drinking beer and sniffing glue," recalls Darwyn Hermann who currently works for the Vancouver park board and still lives on the East Side.

Darwyn's father, Douglas worked as pool supervisor for 20 years at Riley Park and he vividly recollects the confrontations. "They'd get into a lot of fights. During a fight with one of the lifeguards, I hit one of them with a bat. He wanted to lay charges on me but police found him with a gun. They were all on glue and drinking beer," says the 82-year-old Hermann with a slight Welsh accent.

"I mostly got on well with the parents because I didn't call the police on their kids. Parents appreciated me going to them rather than to the cops--who always arrived too late. They lived so close they'd escape into the houses before police arrived anyway. Besides, some of those parents were probably tougher than the police would have been on them."

Vancouver Police Chief Jim Chu remembers the gang well. "The Riley Park gang was a product of the housing project by Ontario and 33rd Avenue. They were lower-income, often single-parent families living there. I didn't think of them that way at the time--they were just kids I went to school with."

Raised in Vancouver in the '60s and '70s, Chu attended Sir Charles Tupper high school, an area that was entrenched with Riley Park gang members. "They wore jean jackets and jeans. Other kids wouldn't wear that — that signified you were a Riley Parker. They were tough guys who fought with tire irons and chains, and if you fought one of them you had to fight them all," Chu recalls.

Chu's first memory of the Riley Park gang was in 1973 as one of the neighbourhood paperboys. "Our shack at 26th and Main won recognition for the fewest complaints in the city. Our supervisor said, 'You guys did great I'm going to buy you some burgers and pop.' The day came and he brought the burgers to the shack and just as soon as he dumped them on the table the Riley Park guys came over and said, 'These look good and we're gonna help ourselves,' and ate them all. The supervisor didn't do a thing. He was too scared to get involved. To look back, it's sort of funny now. Whenever I see the character of Nelson Muntz on The Simpsons, I think of the kids who became Riley Parkers."

But he also gravely recalls many "Riley Parkers" who began with mischief and graduated to serious crimes. "I remember one student from my Grade 5 class who was a hardcore Riley Park gang member. I later played rugby with him at Tupper before he was expelled. Then in his 20s he was arrested for murder. By that time he'd gotten pretty heavily into a life of crime and violence. He's dead now."

While it's difficult to imagine a street gang on the West Side today, across town the Dunbar gang was equally notorious during this period. "Dunbar was much more working class then," recalls 45-year-old Alan Doyle, a longtime Dunbar resident who remembers a different Dunbar than the tony neighbourhood it is today.

"It's not like today with just doctors and lawyers, foreign owners or UBC professors that live here — back then there were a lot of large families in the neighbourhood with lots of kids," Doyle says. "I remember walking by Lord Byng high school around 1971. These guys had an old postal van they'd worked on with 'Dunbar Gang' painted on the side. They were all students but they had beards and looked old — tough looking guys."

Doyle recalls the Dunbar gang's primary hangouts being Memorial West Park and Almond Park at 12th and Alma. The Dunbar gang was blamed for arsons, assaults and high volumes of police dispatch calls around Halloween, but as violent as they could be they were not by far the worst of the city. "They were never as tough as the East Side guys like the Clark Park gang," Doyle says.

Police had become accustomed to dispersing rowdy gangs at Clark Park as far back as the 1950s. By 1970, breaking and entering offences and thefts were common in the area with cases of assaults and rape linked to the Clark Park gang. "Clark Park had an aura and evil stigma about it," says Rod MacDonald who grew up just south of Clark Park in the 1960s.

"A lot of the families in our area weren't good," says MacDonald with a sad tone.

"You had hard working, hard drinking people. There was more than one kid out at 11 p.m. and the parks were where we went. If the parents were awake you didn't go home. When you were at school you had your park buddies. You stuck together because you had to be tough."

MacDonald, who's served 31 years with the Vancouver Fire Department, currently as Battalion Chief, still remembers "a lot of scraps, rock fights, and people with knives. It was mostly fists and kicking. To tell you the truth I remember a lot of the fights were over women," he laughs.

While gangs today opt for semi-automatics over bats and knives, the Clark Park gang displayed an astonishing willingness to violently combat with police that hadn't been seen before or since.

In 1972, two constables were injured in an East Side battle with three Clark Park gang members, one armed with "a length of dog chain with a lead weight tied to one end." But when the Rolling Stones came to town that year, the gang would make its presence known in their most notorious incident yet.

On June 3, 1972 the opening date of the Rolling Stones Exile on Main Street tour, crowds began to gather outside the Pacific Coliseum early that hot Saturday afternoon. Police anticipated the "Clark Parkers" were going to be a problem.

As a result of drug dealing in Clark Park, Const. Ken Doern had gone undercover for five months, infiltrating the gang and learning their intent to crash the concert. Suspected to be increasingly guided by radical subculture groups, the gang was also implicated as a violent instigator in the Sea Festival riot in the summer of 1970 and this time the police weren't taking chances.

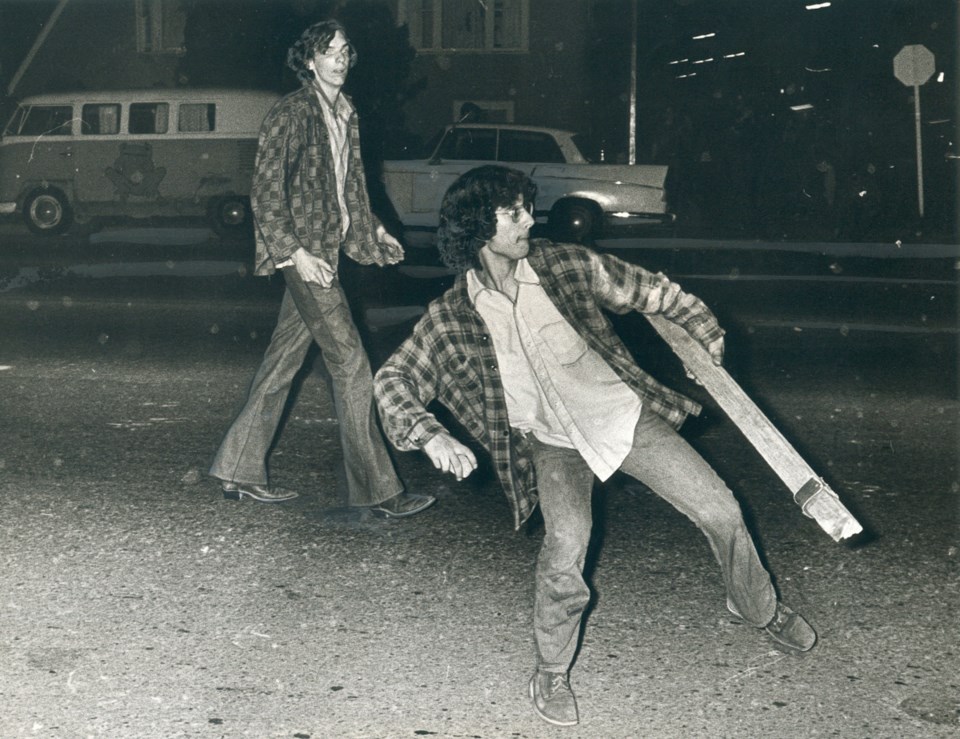

If Doern's information proved true, police were ready that afternoon with more than 50 patrol officers reinforcing PNE security. Two dozen constables in riot gear were also hiding in a nearby building. When the Coliseum doors opened at 6 p.m., some 2,500 fans were left outside in part from concert scalpers selling fake tickets. At 9 p.m. with the show underway and fans still trying to enter, the Clark Parkers--many dressed in checkered loggers "Mack" jackets — hurled a smoke bomb, then a bottle that hit one of the glass entrance doors.

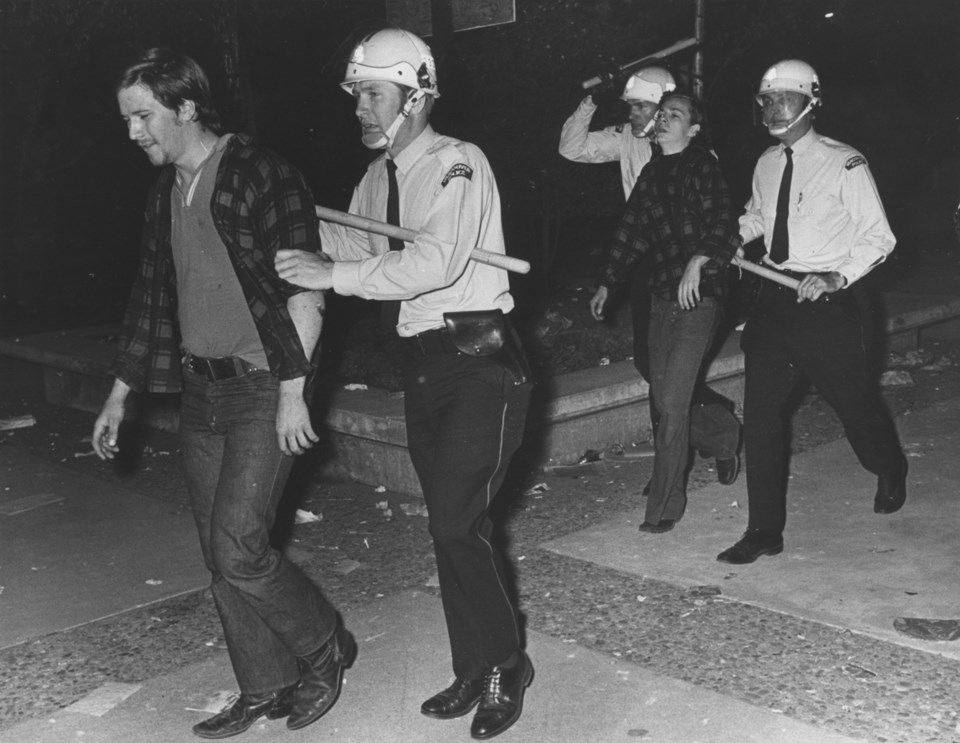

It quickly escalated. Rioters hurled more bottles, boulders and two-by-fours from broken fencing. Cars were damaged along Renfrew Street and the riot continued past 10 p.m. Molotov cocktails were thrown and police attempting to arrest rioters were hit with rocks.

Reinforcements from surrounding RCMP detachments were dispatched and as night set in, screams, swearing, and glass breaking echoed across the concourse. Police feared the situation would worsen if the riot was not quelled by the concert's end, when 17,000 fans would exit the Coliseum and potentially enter the fray.

At 11 p.m., mounted police charged into the crowd, which finally dispersed. By concert's end at 11:30 p.m. the mayhem was over.

Police Inspector Frank Farley, who'd survived the Dieppe raid, was left to shake his head, disgusted at "Canadians fighting Canadians with Molotov cocktails."

The riot left 31 police injured, 13 bad enough they were taken on stretchers to hospital. A total of 22 people were arrested on charges, including possession of an explosive and of a dangerous weapon, which turned out to be a four-foot logging chain with a hook on one end and a leather handle on the other.

By mid-1972, media reports of East Side glue-sniffing gangs crashing rock concerts and committing assaults and thefts filled the newspapers. Rumours abounded the gang had buried weapons in caches in Clark Park. Residents complained the area was in such decline they were selling their homes. Then the last straw happened. Undercover officers learned the Clark Park Gang had become bold enough to plan an ambush of a uniformed constable, luring him with a staged incident.

Police acted with a tactic never before seen in the city and they formed the H-Squad (or Heavy Squad)--a squad of a dozen undercover constables, assigned to go into Clark Park and make themselves targets of the gang.

"They were tough and strong. Christ, if you were under six-foot-four you were only able to serve coffee to these guys," says 69-year-old retired constable Vern Campbell who spent years on the robbery and homicide squad before retiring in 1994.

The H-Squad typically entered the park at night, with one squad member entering first, followed by another two who trailed behind. "The Clark Parkers would attack them and they'd lose — and I wouldn't want to have been a criminal at that point," says Campbell.

There were rumours the H-Squad was armed with baseball bats to fight the gang. Other rumours included police picking up gang members and throwing them off the docks into Burrard Inlet, shooting live rounds into the water only to pull the men out afterwards and order them to never enter the park again.

The rumours may have been just that. But the police are still discreet about the subject of the H-Squad.

Any long since retired and surviving members of the squad who were approached about their duties, now almost 40 years later, declined to be interviewed for this story.

Some 60 residents rallied at the park in July 1972 to protest what they suspected were angry, off-duty police acting without direction from the force. However aggressive the H-Squad's tactics might have been, their success was also noted by many in the neighbourhood. "An old lady who lived across from Clark Park was talking to a uniformed officer one day and he asked her how things were going in the park. She said things were much better since the older gang arrived," recalls Campbell.

Within two months of the H-Squad's activities, the Clark Park gang was effectively disbanded. Their legend persisted for years throughout Vancouver and almost any anecdote of hoodlums crashing house parties involving assaults and thefts by supposed thugs from East Vancouver were attributed to the Clark Park gang spectre.

By the end of the '70s, all the park gangs had disbanded. The end of that era marked a new generation in Vancouver gangs. Over the next two decades a willingness to use guns more than bats and knives, along with extortions and kidnappings, all became hallmarks of the new era. Quickly new Asian groups such as the Lotus and Red Eagles gangs, the Latino Los Diablos and Indo-Canadian gangs emerged. Biker gangs had been present in B.C. since the 1960s, but the Hells Angels did not become an official presence until 1983.

It's no coincidence the new gangs emerged at the same time profits from narcotics and international links between gangs and organized crime became firm.

Chief Chu notes, "We don't see those old types of gangs in Vancouver anymore. Today's gangs are concerned with profit. And because it's been lucrative, we've seen groups cross ethnic lines, which is unusual in the rest of the world. So multiculturalism is alive and well in Vancouver with groups like the United Nations gang now."

Today, the VPD Gang Squad works with proprietors to eject known gang members from nightclubs and restaurants, but in the wake of the Oak Street shooting in December and gang wars in the Lower Mainland in the last two years, would the public welcome a return to the tactics of the H-Squad in dealing with the gangs?

"Back in the '70s a lot of parents would probably be happy if the local beat cop kicked their son's rear end saying, 'Get out of the park and don't come back,'" says Chu, adding that today police must be accountable to the criminal justice system.

"These investigations are complex and very complex by the time they get to court. We have to abide by the rule of law."

As a young police officer on patrol in the 1980s, Chu ran into former schoolmates who became gang members. "I remember going to a call at the home of one guy I knew as a Riley Parker. He'd been booked for rape in a serious incident at the time. It was uncomfortable. At a class reunion last year I ran into one old hard core Riley Park gang member who had just got out of jail and wanted to turn his life around and was doing OK. I had a good conversation with him. Others I've run into from those days have gotten jobs and grew out of that old life."

Whereas gang members in the past quit the scene or burnt out with age, with the shootings the city has seen in recent years, the end of the road for many gang members today seems decidedly fatal.

The Hermanns still live on the East Side and recall seeing some of the old kids — now adults — in the neighbourhood. "Some of them used to hang out years ago at the Biltmore and the old Blue Boy hotel bars." says Douglas Hermann. "I was in there and they recognized me and I was surprised they invited me for a beer. But what became of most of them? I know some later joined the Hells Angels. Others I remember are dead, in jail, moved away or disappeared. The smart ones quit it, grew up and got jobs."

Back at Clark Park, Carroll says she's proud of the area where she grew up, but she knows how different today's East Side is from her youth. "The neighbourhood has changed so much since then. But I still don't like going near the park."