It was the height of the Great Depression and Vancouver’s preeminent sculptor was reduced to creating garden gnomes for rich families on the city’s West Side.

Then Charles Marega heard about a commission to create two sculptures for the southern entrance of a new suspension bridge being constructed over the Burrard Inlet.

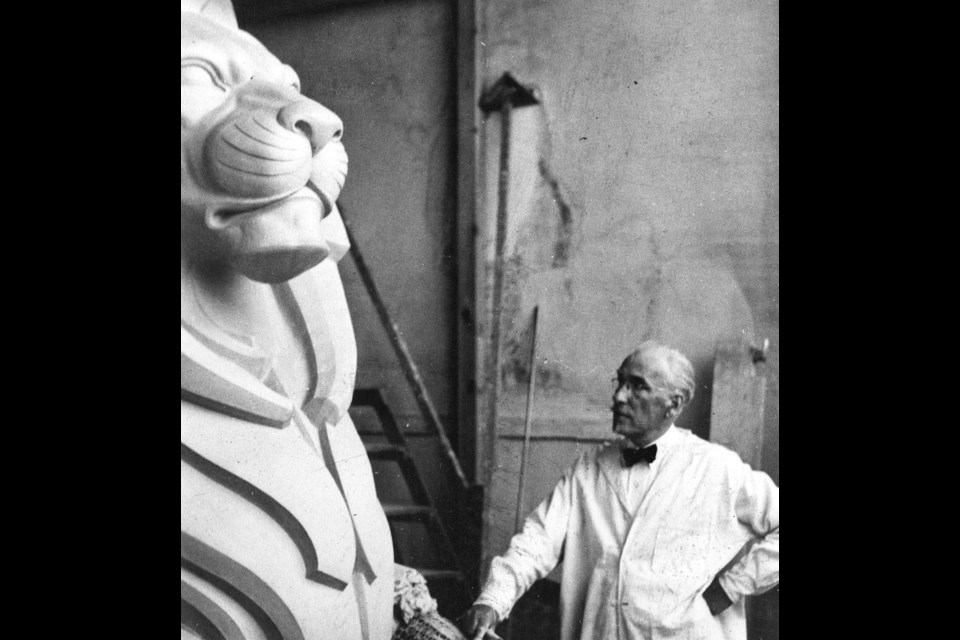

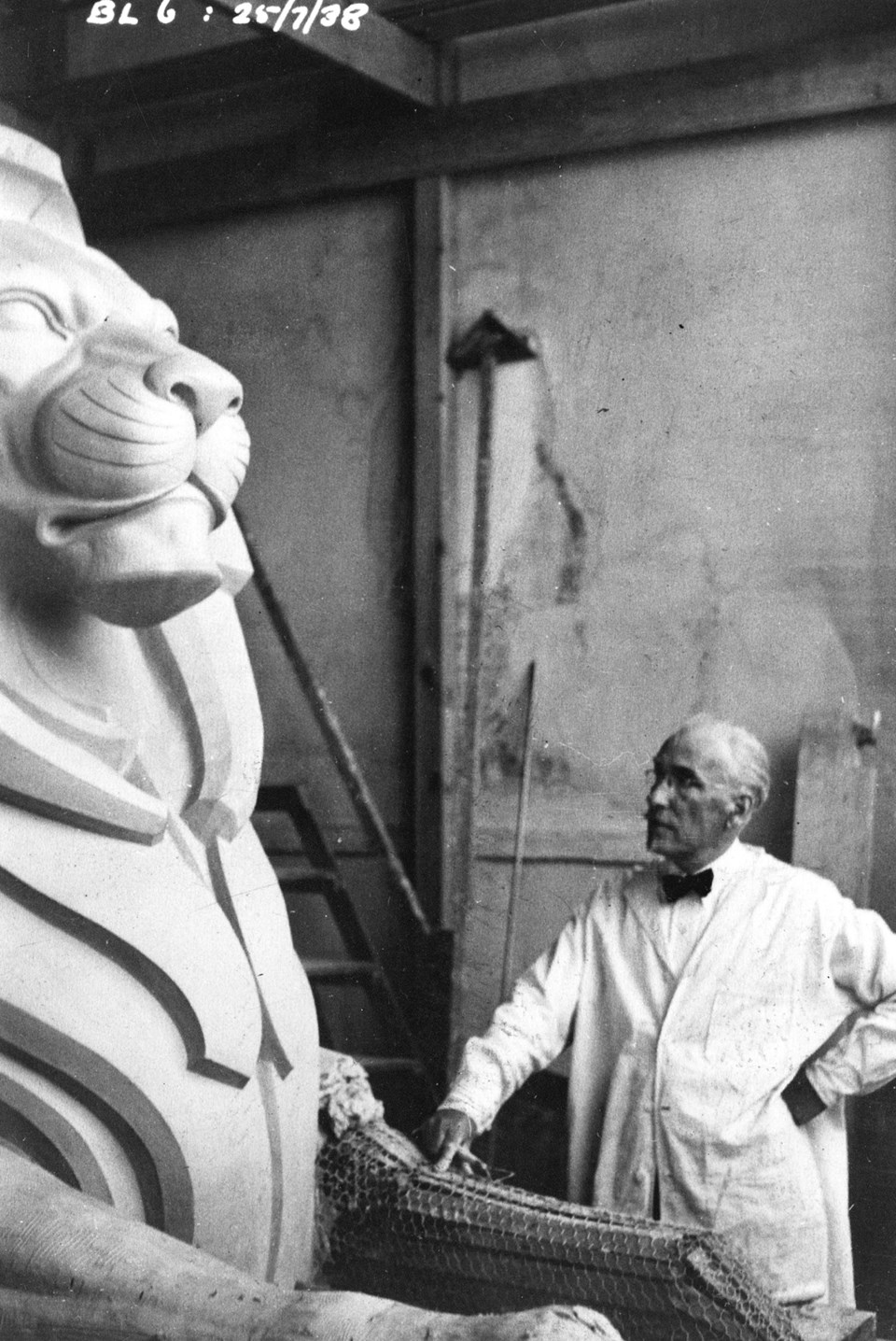

“Thank God I have work now,” he wrote to his family in Switzerland. “I am modelling a lion for Vancouver’s suspension bridge. I had much trouble to get the work. But the president of the bridge committee [A.J. Taylor], who is a long-standing friend of mine, and his wife, who was a good friend of Mama’s, finally assigned the work to me.

“I would have preferred the lions to be in bronze or stone — but it has to be cheap, which annoys me…. However, I have to content myself to get work at all.”

An archival photo from Jan. 25, 1939 shows Marega’s two Art Deco-style lions being installed at the edge of Stanley Park. Two months later, at the age of 67, Marega died of a massive heart attack after teaching a class at the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Arts.

His obituary in the Province said he had $8 to his name.

The lions may not have made Marega rich, but they did become his enduring memorial.

“We are truly touched by his legacy before we even know his name,” Cloverdale-Langley City MP John Aldag said a small ceremony at the Italian Cultural Centre in East Vancouver to unveil a heritage plaque in Marega’s honour earlier this month. “His significance is immeasurable.”

As well as the two lions, Marega created:

• the 1936 sculpture of Capt. George Vancouver, which stands in front of city hall

• the heads of George Vancouver and Capt. Harry Burrard on the Burrard Street Bridge

• the bust of Vancouver’s second mayor, David Oppenheimer, in Stanley Park

• the fountain in Alexandra Park to commemorate Joe Fortes

• the memorial to U.S. President Warren Harding in Stanley Park

• the ornamental ceiling work at the Orpheum Theatre

• the King Edward VII fountain at the Vancouver court house

• 14 figures and six medallions on the provincial library building in Victoria.

He is also credited with being one of the founders of the Vancouver Art Gallery and the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Arts, which would one day become Emily Carr University.

“There has never been another sculptor who did so much work for this city,” art historian Peggy Imredy is quoted in a 1975 story in the Province.

Carlo Marega — he would Anglicize his name to Charles when he immigrated to Canada — was born into a middle-class Italian family in Lucinico, which was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He studied sculpture and the trade of artistic plaster design in Italy and Vienna. After working in Zurich, he and his beloved Swiss-born wife Bertha moved to South Africa in 1906.

In 1909, the Maregas were on their way to California when they made a stop in Vancouver. The North Shore mountains reminded Bertha so much of her home in Switzerland that she convinced her husband to stay put.

“The Maregas were thought a handsome couple, she was beautiful and he was finely groomed with a waxed mustache. They made an impressive entrance at events,” says the City of Vancouver website.

While other Canadian cities such as Toronto and Montreal were caught up in “statuemania,” Vancouver was slow off the mark, Aldag said at the plaque unveiling. Until Marega’s arrival, most three-dimensional public artwork in the city had been created by First Nations artists. It was Marega who brought European traditions to the city and, for the next 20 years, he was the only sculptor of his kind to live and work here.

In fact, sculpture was such an unknown art that when the city discussed hiring someone to create the bust of David Oppenheimer, it first approached an American sculptor — only to discover he had died two years earlier. The job became Marega’s first commission in British Columbia.

The Oppenheimer sculpture illustrates Marega’s mastery of his classical training. However, when he was given more artistic licence, his pieces are also evidence of his love of the Beaux-Arts and Art Deco movements.

was also evolving. Up until 1925, people wanting to cross the Burrard Inlet had to travel to the North Shore by ferry services. The first bridge to span the waters was a low road-and-rail bridge at Second Narrows. It was damaged in a marine accident in the 1930s and, as the North Vancouver Museum & Archives says, its temporary absence added to the urgency to build a bridge across the First Narrows as well.

“Vancouver businessman and engineer Alfred James Towle Taylor envisioned the [Lions Gate] bridge as a means of connecting the downtown city core with the development potential of the north shore,” says the museum’s attractive online pictorial archive. “He foresaw that the view-blessed slopes of West and North Vancouver were ripe for residential settlement, including the elite British Properties he created and designed…

“Taylor spent years tussling with government and marine authorities of the Lions Gate Bridge. Eventually he got the support of Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King and the project went ahead. Taylor needed investment capital to fund the almost $6-million bridge, plus another $4 million for land development. He found his backers in the British Guinness family, including Lord Scarborough, whose descendants own large tracts of prime north shore property to this day.”

Although it was a hugely expensive undertaking, the bridge also became “a beacon of progress and hope for better times” as the city began to release itself from the clutches of the Great Depression.

But that didn’t leave much money for Marega’s statues. In one of the few photos of him in his studio, you can see the wire and wood frame of one of the lions’ legs before Marega encased it in “the lowliest material of all” — cement.

Inside those two-metre-tall sculptures are also a hidden treasure: As a favour to his benefactor, A.J.T. Taylor, Marega encased some personal artifacts from Taylor, including his baby shoes and his account of his struggle to get the bridge built.

Massimiliano Iacchine, Vancouver’s consul general of Italy, can’t help but imagine that Marega’s sculptures of the proud and dignified lions guarding the Lions Gate Bridge were inspired by his travels in Africa.

Taylor, whose ashes were scattered off the bridge following his death in 1945, also asked Marega for smaller versions of the lions sculptures, which he proudly placed on two plinths at the entrance way to his waterfront mansion in West Vancouver, Kew House. Future owners later donated them to the North Vancouver Museum and Archives. Marega’s maquettes — models of the sculptures — are in the Museum of Vancouver collection.

The Italian Cultural Centre is very pleased to be the home of the Marega historical plaque, which has a dedication in English, French and Italian.

“Although he’s but one of our distinguished Italians, he is especially etched in our history,” said Ray Culos, a retired journalist who has written extensively about Vancouver’s Italian community.

Culos is the one who approached Parks Canada to honour Marega. His father knew the sculptor and worked with him on the community’s Parade of Progress float at the PNE in 1936.

Pleased to have an Italian artist’s influence and impact honoured in such a way, Iaccchine said, “Thank you Italy, thank you Canada, thank you Carlo.”

With thanks to Parks Canada, which oversees the historic plaque program, vancouverhistory.ca, Vancouver Heritage Foundation, North Vancouver Museum and Archives, The Province and the Italian Cultural Centre for their historical archives and research.