Victoria has one (Lisa Helps). Montreal has one (Valérie Plante). Surrey has one (Linda Hepner). Even Nanaimo had one back in the early 1990s (Joy Leach). In fact, many Canadian cities have had one.

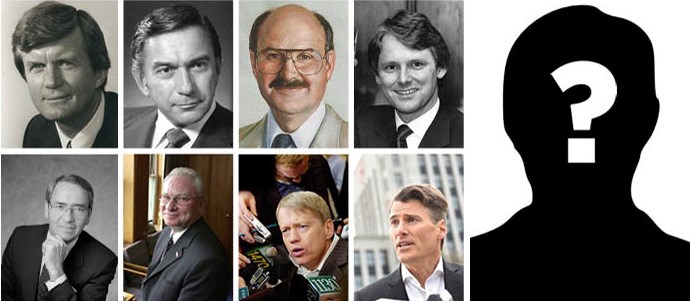

But not Vancouver. A city that many consider progressive has failed to elect a female mayor.

Ontario was the Canadian leader on this front — Barbara Hanley became the country’s first female mayor in Webbwood, Ont. after she was elected in 1936, while Charlotte Whitton of Ottawa, Ont. became the first woman elected mayor of a major Canadian city in 1951.

One of the country’s longest serving Canadian female mayors was “Hurricane Hazel” McCallion from Mississauga, who retired in 2014 after 36 years. But it can be a tough job. Just ask Maple Ridge mayor Nicole Read who stopped making public appearances for a month in 2017. Online attacks — often sexist ones — emerged after she expressed support for a homeless shelter. The RCMP ended up investigating what it called “credible threats to her personal safety.”

In Vancouver, however, a woman still hasn’t landed the city’s top political job despite voters having already elected a female premier — Christy Clark, who, incidentally, hoped to run for Vancouver mayor under the NPA in 2005 until Sam Sullivan pulled off a surprise win for the nomination. Sullivan subsequently won the election against Vision’s Jim Green.

In recent years, the closest the city has come is when NPAer Suzanne Anton, who later became Attorney General under the B.C. Liberals, battled Vision’s Gregor Robertson for the mayor’s chair in 2011. Anton captured 58,152 votes to his 77,005.

Looking back to the 2014 municipal race, COPE, whose support had plummeted by this point, fielded Meena Wong as its candidate against Robertson and the NPA’s Kirk LaPointe. Wong earned 16,791 votes to Robertson’s 83,529 and LaPointe’s 73,443.

In 2002, Jennifer Clarke ran for mayor under the NPA against COPE’s Larry Campbell. She earned 41,936 votes compared to Campbell’s 80,772. Valerie Maclean, vcaTEAM’s pick, only earned 7,843 votes for a distant third-place finish.

This brings us to the upcoming municipal vote slated for Oct. 20, 2018, and the slew of questions raised each election cycle: Which mainstream parties, if any, will field female mayoral candidates? Will Vancouver finally elect a female mayor? Does it even matter?

The Courier talked to three prominent past and present Vancouver politicians to get their thoughts about the prospect of a woman winning the elusive seat, including Vision Vancouver councillor Andrea Reimer, Green Party councillor Adriane Carr and former COPE councillor Ellen Woodsworth, founder and chair of Women Transforming Cities International Society.

ANDREA REIMER

Reimer, a three-term Vision councillor who also spent a term as a Green Party school trustee, was long thought to be a contender, along with Raymond Louie, for Vision’s mayoral nomination if Robertson ever stepped aside. That possibility evaporated for Reimer last October when she revealed she won’t seek re-election, citing personal reasons.

“In a world that I believe is meant to be more like jury duty than a career, I’ve done my term, my duty, and I would like to get back a life that has a private aspect to it,” she told the Courier recently, not long after Robertson announced, on Jan. 10, that he, too, won’t seek re-election.

It’s now unclear whether Vision will run a mayoral candidate at all — the party might back a progressive independent candidate.

Reimer said it’s both surprising and not surprising the city hasn’t installed a female mayor, while adding there’s no single factor that explains it; rather it’s a confluence of factors: Fewer women have run for mayor and, of the women who’ve run, it tends to be when a party has faint hope of victory.

“A not uncommon thing for women in politics is that women leaders tend to be put in when people feel like there’s less chance of that party having a shot. It’s a double chance for a party to look magnanimous or gender sensitive and let a woman take the fall rather than a man,” she said.

The opportunity for women to run for office is further reduced, according to Reimer, due to wage and economic inequality, which she says is quite pronounced in Vancouver, even relative to other Canadian cities. As a result, women’s vulnerability in terms of issues such as safety and access to affordable housing is much higher.

“So would that lead to a woman becoming mayor? Probably not,” said Reimer, who spoke to the Courier the day before council approved its Women’s Equity Strategy, which outlines how to make Vancouver “a fair, safe and inclusive city for all women, including self-identified women.”

From a political perspective, women have made strides, including successfully landing city council seats. This term, five of 10 councillors are female, although four of them have last names starting with one of the first few letters of the alphabet, which Reimer calls “a unique but important advantage here.”

(Some suggest alphabetical ballots favour candidates with A, B, C and D names.)

“But we have a mayor, an acting mayor and a deputy mayor none of whom are women despite the fact half of council are women,” she said. “So just because you have women elected in larger numbers doesn’t mean that they’re going to get any more access to power.”

Raymond Louie was appointed acting mayor in December 2014. Tim Stevenson was appointed deputy mayor in July 2017. While Reimer was appointed deputy mayor from early December 2014 to the end of December 2015, she points out that during this period the other two positions, mayor and acting mayor, were both men “even though in theory with 50 per cent men/women councillors it should be possible to have two of three positions as women but that’s not happened while it has been two out of three or three out of three men.”

Over the years, meanwhile, Reimer has chaired the Canadian Women Voters Congress and worked to recruit women to sit on political party boards, to be candidates and to support other female candidates, but she always warns them it’s a tough road and the same hurdles they face in other jobs exist in politics.

“Because there’s not just perceived but actual power on the table, I would suggest, from my own experiences, it’s somewhat magnified,” she said.

Should there be rules around gender parity in political races? Reimer said it’s a tough call. She’s always been “challenged by the idea of legislated gender parity,” but she hit a “breaking point” in 2016 when one of the appointing agencies to the city’s advisory committees told her there weren’t good women to sit in a position.

“In the face of that attitude, perhaps legislating a parity requirement would be the best way to advance the appointments, which it was,” Reimer said. “It turns out we now have well over 50 per cent women appointed. It turns out there are tons of women who are qualified, not surprisingly, to sit on advisory committees.”

But in an electoral process, she’s still not convinced it would be fair to have women “own” a failure that’s not theirs to own.

She bristles at a question about whether male politicians, such as Robertson, should step aside to make space for female mayoral candidates, “as if it was his to give the space.”

“That’s what worries me about a party running a woman for the sake of it… if it’s still largely men controlling the board and backrooms and the strategy, who believe they made this room for the woman, how does that give her a mandate to become a mayor like Gregor got to be or Larry Campbell got to be or Philip Owen got to be?” she said.

Reimer said it would be “fantastic” if a woman gets the job because attitudes have fundamentally changed, but if it's just a paper candidacy, she’s not OK with it.

Regressive attitudes are among day-to-day irritations Reimer contends with in politics, including the number of times she’s interrupted when chairing meetings.

“I’m interrupted by men and women… When Gregor is the chair, I rarely hear councillors interrupt him. Me as the chair? Every single meeting somebody is going to interrupt me while I’m talking,” she said.

“I would trade any chance of a woman becoming a mayor in a heartbeat if it meant that women have the same economic opportunities, the same feeling of safety that men have, the same access to education — all those things. If they could get through a meeting without being interrupted — that would be worth a lot more than a woman as a mayor, but I suspect the two are very closely interrelated.”

ADRIANE CARR

Could Green Party Coun. Adriane Carr be the next mayor of Vancouver? She topped the polls in the 2014 race for council seats with 74,077 votes. But the Greens still haven’t decided whether they’ll field a mayoral candidate in 2018. If they did, and Carr sought and won the nomination, she would forfeit the far better odds of winning another term as one of the city’s 10 councillors.

Carr told the Courier this week that these decisions will be made “sooner rather than later” as the party is going through a more “robust” planning process right now, looking at questions such as how many candidates to run and which incumbents are interested in running.

She isn’t sure why a woman hasn’t nabbed the mayor’s seat yet, although her theory is it might have to do with party politics.

“Given the result in Montreal, which was very exciting, I can’t honestly say why it hasn’t happened yet in Vancouver,” she said. “Obviously, we have party politics here, so that makes a difference and, in other cities, that doesn’t happen. There are a lot of cities where women run and win. Victoria is a good example [and] Chilliwack. So is party politics the problem? Parties end up going through a more rigorous process, and you have to raise the funds…”

When she was co-chair of the Canadian Women Voters Congress national campaign school, which trains women to run for politics, Carr learned there are “huge” barriers for women, not the least of which is fundraising.

“It’s a more difficult task given you need connections that are broad into a well-heeled community. And you need more money to run for mayor, that’s for sure,” she said. “I don’t think that the voters of Vancouver wouldn’t want a woman mayor. I think it’s more the party structure has inhibited the nomination of women.”

Carr believes women dampen down hyper-partisan politics, which she’s convinced turns voters off, and that it’s time for a woman to be elected as Vancouver’s mayor because there’s something unique they offer in politics that’s recognized world-wide.

“It’s not universal, it’s not 100 per cent the case, but, in general, women tend to lead a more collaborative process in politics. That’s what’s needed and, I think, that’s what the voters want. The polarizing kind of politics that we see, for example, in the United States with President Trump is very debilitating in terms of people’s trust in government and [their] hope that government leads to good decision-making that benefits the whole.”

ELLEN WOODSWORTH

Women’s place in politics is central to Woodsworth’s work with the Women Transforming Cities International Society. She spoke with the Courier Jan. 16, the day the federal government announced the society would receive $282,000 in funding for a project to help remove barriers to women’s political and civic engagement in Vancouver and Surrey. The society will work in partnership with the Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement of Women and work closely with Health Nexus and Equal Voice.

Woodsworth conceded it’s odd that, in Vancouver, a woman has yet to win the mayor’s chair, especially in light of Dianne Watts’ and Linda Hepner’s success in Surrey.

“Vancouver has all the policy. There’s a women’s advisory committee and it’s got the gender equity strategy [that went] before council [Jan. 17]. Surrey has none of that, but they’ve had two women mayors and a majority of women on council there for years.”

Part of it, she suspects, is that Vancouver is a big city dominated by the party system and the parties consistently pick male leaders who are professionals with financial expertise.

Meanwhile, once you’re elected in any political position, she said it can be “pretty nasty” because you’re subject to incredible personal scrutiny, the media is tough and some woman haven’t learned to debate in a council setting.

“If you talk to most women who’ve been elected, that’s what they like least about being elected… being in council chambers or being in the house. That’s not a framework they feel comfortable in,” she said.

But Woodsworth thinks there’s “a really strong possibility for a woman to run and get a lot of support” in the 2018 mayoral race.

“Part of it is we’re in a time of change. People are looking for a new face. And the other [part] is this tremendous up-swell of women feeling it’s important to step up and stand up to power that has not been theirs, and to have women in power who could speak up for women’s rights,” she said. “Who knows where that’s going to emerge?”

She said former Pivot Legal Society executive director Katrina Pacey’s name has been fielded as a possible person who could capture support of several progressive parties, while former Conservative MP Wai Young is among those who might seek the NPA nomination.

Woodsworth is convinced having “a capable women to stand up and be a symbol” is important.

“We’re talking about a level of government that’s closest to the people. You do want to have people in elected office that reflect the populace… You’ve had some diversity in council and to have a woman mayor, if she is able and she brings to it a politic that really is inclusive and brings the city together [it would be good],” she said.

“Because the city is quite divided right now. There’s a lot of anger… whether it belongs to Gregor is a different question, but there’s a need for somebody who can really bring people together and give them hope that this city can really be theirs again. There are some women around who could do that. And it would be really significant for women to see that.”

Note: Suzanne Anton did not respond to Courier's requests for comment.