The Atlantic Ocean covers 106 million square kilometres so the chances of finding a wayward six-metre sailboat more than qualified for any needle-in-a-haystack requirements.

That’s why the rescue of Ada, an autonomous “sailbot” that was attempting to make the first skipper-less crossing of the Atlantic Ocean, is being considered a miracle.

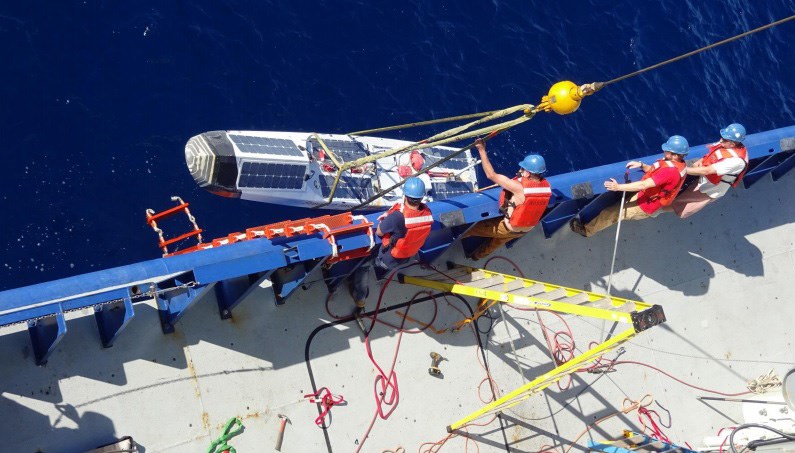

On Dec. 1, crew aboard the RV Neil Armstrong noticed Ada 200 kilometres off the coast of Florida. They became more intrigued when they realized that Ada, which had lost her mast when she lost her way in a storm, had been built by University of British Columbia students on the other side of the continent.

The crew lifted Ada onboard and contacted UBC to let them know that what once was lost had now been found 7,000 kilometres later.

“We were very excited,” says Kristoffer Vik Hansen, who spearheaded the world-record-breaking project.

A team of about 60 UBC students created Ada, named after Ada Lovelace, the world’s first computer programmer (and daughter of 19th Century poet Lord Byron.) It was hoped Ada would be the first self-navigating sailboat to cross the Atlantic.

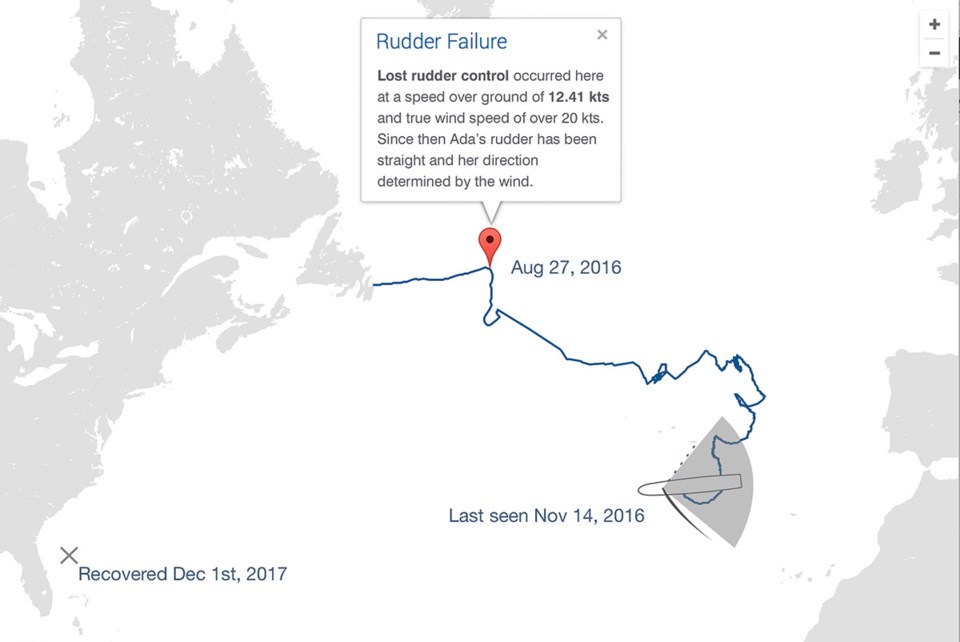

Since the shortest distance is from Newfoundland to Ireland, a small group had travelled to the East Coast in August 2016 for the launch.

Ada was equipped with enough solar panels and lithium batteries to operate all the navigation and communication tools the students had created for the robotic sailboat. By reading the information that Ada supplied with her infrared camera detection technology, the students could let Ada know when and how to avoid icebergs and cargo ships while staying on course in current weather conditions. If she was getting off-course, they could set her back on the right tack.

When the students lost contact with Ada during a storm four months into her journey, Ada had already set a record for longest distance autonomously sailed across the Atlantic — 1,000 kilometres.

Although they were unable to chart her course for the next 14 months, Hansen estimates she travelled an additional 7,000 kilometres.

A member of the UBC team is expecting to travel to Woods Hole, Massachusetts to retrieve the Ada’s black box when the RV Neil Armstrong returns to port in mid-December. It’s Hansen’s hope that UBC also thinks it worthwhile to return the Ada itself to Vancouver.

Hansen says that not only did Ada far exceed their expectations of how long she’d last in the rough and storm-swept Atlantic Ocean, but when she was damaged in the storm, they had all but abandoned hope she hadn’t sunk.

The fact that she survived is a feather in the team’s cap.

What pleases him the most is proving that a team of students can make something “pretty fricking incredible.”

“We were taking [autonomous technology] to the next level,” he says. “This is happening now. It’s important to show that the world is moving towards an autonomous future.”

While there’s no skipper to boast of such accomplishments, Hansen says the technological advances devised by the students will be useful in other ventures.

“We see all marine vessels using this technology,” he says.