On Wednesday, April 17, something extraordinary happened at BC Place during an MLS game between the Vancouver Whitecaps and Los Angeles FC.

With about 10 minutes to go in the first half, hundreds of Whitecaps fans, including row upon row from the club’s diehard supporters groups, stood up and walked away from the action. It was a protest – the fans, quite literally, turning their backs on the Whitecaps. They collectively left their seats and headed to the concourse where they stayed until the start of the second half.

It didn’t, however, have anything to do with the players on the field at the time or the action in the game. It all started with the words of one woman, a North Vancouver soccer player named Ciara McCormack, who in February wrote a blog post on her personal website. She labelled the post “A Horrific Canadian Soccer Story – The Story No One Wants to Listen To, But Everyone Needs to Hear.”

The fallout of the post is still being felt throughout the soccer world in Canada. Along with some serious allegations of mistreatment of players, there is a call to action to clean up the way sport is administered in this country.

But who is Ciara McCormack? Unless you’re deep into the women’s soccer scene, you may never have heard the name until it started popping up on Twitter after her blog post started going viral. It turns out this soccer player turned whistle blower is someone who has been fighting for what she believes in all her life, someone who is not afraid to take a stand even when it is uncomfortable, or even personally damaging.

There are some, it appears, who are reluctant to hear her story. But as the walkout protest shows, this issue does not appear to be going away anytime soon. Those who know McCormack know one thing, something that many others are now starting to learn: she is not going to let this go without a fight.

Born in North Vancouver, roots in Ireland

The blog post was one that McCormack had written over and over again, weighing what would happen if she shared the unpleasant story with the world. Could she handle the stress? Was she going crazy? Would it damage her career?

On Monday, Feb. 25, her finger hovered over the “Post” button once more. Would this be the day that she’d send it?

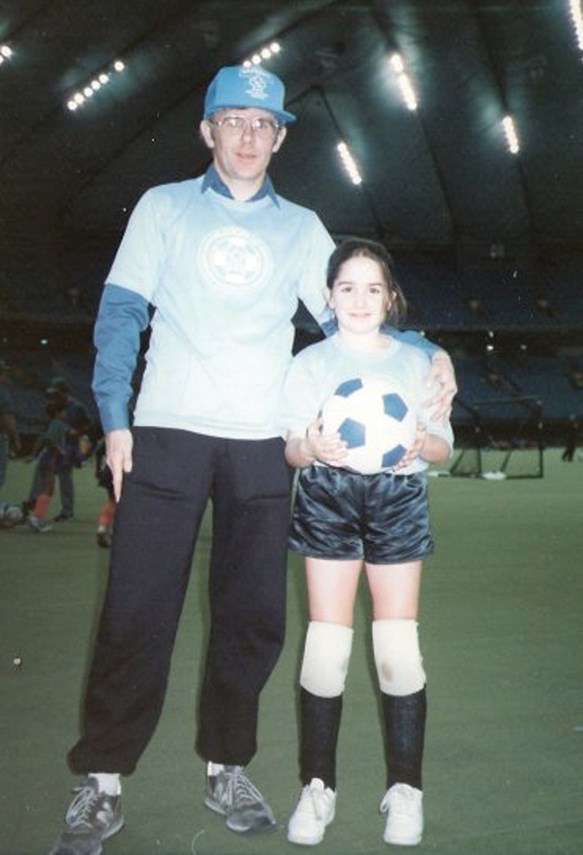

To understand how she got to that point in her life, it’s important to go back right to the beginning. McCormack is very much a Canadian, born and raised in North Vancouver, but her upbringing was rooted in Irish traditions – both her mother Mary and father Barry were immigrants from Ireland. When it came time to sign up for sports in Canada, the family had no thought of putting Ciara into soccer. Girls in Ireland didn’t play soccer back then. But when Barry went to sign up Ciara’s brother Connor, two years younger than her, Ciara sensed the injustice of it all, and was having none of it.

“My brother was playing, and I was throwing a fit,” says Ciara, recalling the story while sitting in a North Vancouver coffee shop. “How come he got to play soccer and I didn’t?”

Her dad says it was an honest mistake.

“I never even thought of signing Ciara up, and couldn’t wait to sign Connor up,” says Barry. The gender imbalance didn’t last long. The next week, Ciara was on a team of her own, and Barry, arriving at practice with an Irish accent, was promptly named head coach, a role he held for several years. She wasn’t always the best player – Ciara says she sat on the bench for most of the year when she made her first Metro team, her big break coming only after one of her teammates was grounded for sneaking out – but she was always one of the toughest, says Barry.

“She was very aggressive,” he says. “Coming home from games she’d always debrief the games and tell me to be brutally honest about how she played. She was driven.”

A defining moment of her youth career came during her Grade 12 high school season with the Handsworth Royals. The team made it to the provincial final, but it came at a high cost for McCormack, who clashed heads with another player in the semifinal and was essentially knocked out cold, gushing blood. She was taken to hospital but begged them not to give her stitches to seal the wound because it might stop her from playing in the final.

Whatever begging she did worked, because she was back out on the field for the final. It didn’t go how she hoped.

“I woke up the next day obviously feeling like I’d been hit by a truck, and played so bad in the final and thought for years that I was this big choker in big games.”

The title went to their fierce cross-town rivals, the Argyle Pipers. McCormack knows things would have been much different if that incident played out now in the concussion era.

“I would have been in a dark room for like six months if this had happened in 2019,” she says.

Her disappointment at provincials didn’t stop her from moving to the next level, as McCormack headed south to play NCAA Div. 1 soccer, first at Yale University where she did her undergrad, and then at the University of Connecticut where she earned a master’s degree in sport management.

She then embarked on a pro career that took her to teams and leagues around the world, including stops across Canada and the United States as well as Denmark, Norway and Australia. In 2002 she became the first Canadian to win a medal in the UEFA Women’s Champions League, claiming silver with Danish club Fortuna Hjorring.

She was always driven by the goal of playing for the national team and going to the Olympic Games. She idolized some of the older national team players like long time captain Andrea Neil, Amber Allen and Martina Franko.

“I really looked up to them,” she says. “I think that playing for Canada to me kind of meant being like them. They were the most inspiring, hard-working, character- and integrity-filled people I had ever met.”

She often trained alongside national team players, and with her pro experience believed she was on track to one day play for Canada. But that never happened, which is where the story McCormack published in her blog begins.

Whitecaps and national team tightly linked

In the mid-2000s, the women’s national team and the powerhouse Vancouver Whitecaps became linked – Vancouver became the de facto home for the national team program, as most of the players who played on the national team also played for the Whitecaps.

This “one pathway” system put a lot of power into the hands of a few coaches and administrators, says McCormack, adding that the feeling was that if you stepped out of line with the Whitecaps, it would jeopardize your status with the national team. McCormack says this created a fear-based, anxiety-ridden atmosphere that included one coach in particular, who worked for both the national program and the Whitecaps, who “started to bully and manipulate” players. McCormack says she overheard the coach reducing a teammate to “hysterical sobbing” as he “berated her” for asking for a larger room in the team’s summer housing quarters.

“He reminded us often that he was the reason we were training with the national team, with the obvious underlying insinuation that he gave us the opportunity and he could also take it away,” McCormack writes.

She says she decided to speak up about the environment in the club, and, joined by another player, met with a high-ranking Whitecaps executive, asking for help and anonymity. McCormack writes that three days later the Whitecaps executive told her that he had shared all of her concerns with the coach and had also told him which players had made the complaint.

She felt “terrified and speechless” about this information being shared with the coach, and that summer moved from the Vancouver Whitecaps to the Ottawa Fury.

She surmised at the time that standing up to the coach and then leaving Vancouver might cost her any chance she had at making the national team. She was right – she never trained in the national team program again. But knowing what she knows now, she says she’d make the same decision every time.

“How people are treated is more important to me than national team caps,” she says, adding that she doesn’t know for sure that she would have eventually been selected for the national team even if she had stayed quiet.

“It’s subjective. I don’t know,” she says. “I definitely didn’t do myself any favours to get selected by being a person that spoke up about stuff.”

By the following year McCormack was the captain of the Ottawa Fury. She also made her debut with the Irish national team, her heritage allowing her to move to a national squad that welcomed her into a prominent role immediately.

But the situation McCormack left in Vancouver wasn’t getting any better for her old friends and teammates, she says. Eventually a mediator was brought in, and the coach McCormack had complained about was relieved of his duties with the Whitecaps and the national program less than two months before he was to be the head coach of Team Canada at the U20 World Cup.

Announcements at the time said the coach, the Whitecaps and the national program “mutually parted ways.” McCormack, who spoke to the mediator as part of the investigation, says that the players were told by the mediator that part of the investigation’s findings would be a recommendation that the man in question should not coach anymore.

McCormack played one more stint with the Whitecaps in 2011 and says that the environment was mostly unchanged. On top of that, she later learned that the coach who had been let go was back working with underage girls at an elite club in British Columbia.

McCormack says she was shocked one day when she was on the North Shore watching a youth game and heard his voice yelling instructions to players on a nearby pitch.

“It was just surreal,” she says. “I hadn’t seen him since I walked away from the Whitecaps in 2007 because of all this stuff. … It was just shock, really. I’d heard about it, but to actually see him back out on the field was just like, [I was] angry at everybody.”

Blog post goes viral

On Feb. 25, 2019, McCormack’s finger hovered over the “Post” button on her blog entry once more, inches away from launching 7,000 words expressing her anger and frustration at the events described above as well as much more she felt was unjust about the way that elite women’s soccer was set up in Canada.

A few other events had taken her to that point as well.

Just weeks before, McCormack was captivated by a series of investigative pieces from CBC documenting abuse in amateur sport in Canada. McCormack says she took strength from that series, hearing from victims who decided to come forward.

She was also spurred on by a chance encounter in the checkout line at Whole Foods. McCormack says a soccer player, about 10 years younger than her, recognized McCormack, and as they chatted it became clear that the experience for this young player moving through the elite soccer world in British Columbia was not much different than it had been for players like McCormack who came through the program before her.

“She looked at me and she was like, ‘Ciara, I’ve been in therapy the last five years because of the bullying,’” says McCormack, adding that this gave her the push she needed to take her story public. “If I’m not going to say something, who is?”

McCormack had already shown on multiple occasions in her life that she was willing to take a stand against things she felt were wrong. It’s part of who she is, she says.

When she was six years old McCormack’s mother was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Mary McCormack has used a wheelchair for nearly 20 years, and remains a source of inspiration for her daughter.

“Everyone loves my mom,” McCormack says. “When you see your mom have the strength she has every day and has a positive attitude despite what’s going on, she’s definitely the most inspiring person I have in my life.”

Barry McCormack believes that his daughter gains strength from Mary.

“When (Ciara) gets down, she thinks about her mom in a wheelchair and the battle her mom has on a daily basis just trying to put on her shoes and things like that. She’s got a very good outlook and perspective on life as a result.”

And there’s something about the family’s heritage, says Barry – those Irish roots come with thorns. Right from the moment he neglected to put his daughter into soccer, Barry has known that his daughter will always raise her voice if she feels mistreated.

“It’s the Irish blood,” he says. “The Irish have been disadvantaged and downtrodden, and we don’t take it kindly.”

On that Monday morning, McCormack finally clicked “Post.”

“I was terrified. Absolutely terrified,” she said, sipping her coffee three days after the post went live. McCormack nervously fingered her long black hair as she unspooled her story to a reporter in the coffee shop.

The fallout continues to this day. In the weeks following her blog post, news outlets slowly started to pick up the story and dig into the accusations, while her post was shared widely on social media. The coach in question – dropped by the Whitecaps and national program in 2008 only to reappear on the sidelines again in B.C. – was suspended by his club, pending an internal investigation, one day after McCormack’s blog post went live.

One month later, Andrea Neil – a member of the Canadian Sports Hall of Fame and the Whitecaps Ring of Honour – released a statement in support of McCormack.

“I feel I need to add my voice to Ciara’s as she continues to challenge some of the systemic issues within the world of youth sport here in B.C. and beyond,” Neil writes. “I do not believe that the system supported Ciara and her teammates back then and, although I hope I’m wrong, I do not believe the system functions any better today. … I for one am honoured to be able to call Ciara my teammate.”

Soon after that, a group of 12 players, since updated to 13, from the 2008 U20 women’s team released a statement expanding on the allegations outlined in McCormack’s blog post.

“During our time as part of the U20s, we each witnessed incidents of abuse, manipulation, or inappropriate behaviour toward players,” they wrote. The statement includes allegations such as the coach rubbing a player’s thigh during a car ride; sending sexually suggestive text messages; inviting a player who was not in the starting lineup to his hotel room and asking “what are you going to do about it?”; and telling a player that he liked the way she looked in a wet, white jersey, and that he chose for the team to wear white on a rainy day for that reason.

Those allegations are unproven. Earlier this month the Vancouver Police Department said they were aware of the allegations, but didn’t confirm if they were investigating. The North Shore News reached out to the coach for comment and did not get a reply.

The Whitecaps have released four statements since McCormack’s blog post. The first three were unsigned, while the fourth – released on Wednesday, more than nine weeks after McCormack’s blog post – was signed by co-owners Jeff Mallett and Greg Kerfoot. This week’s statement contained something that was not in the first three: an apology.

“As we reflect on what happened in 2008 and the blogs that have been published over the last several weeks, we express sincere regret and empathy for the harm that has clearly come to many women who participated in our program at that time. The pain and suffering these women feel is real and something we care deeply about. And while we sought and acted on the advice of the best available counsel at the time, it is clear that people were deeply affected. For that we are sorry.”

The latest statement also lays out a detailed timeline of the steps taken by the club in response to complaints beginning on May 23, 2008, including hiring a lawyer as an ombudsperson and, upon her recommendations, requiring the coach to take “training which explicitly outlined appropriate boundaries and behaviour;” terminating the employment of the coach after receiving additional complaints later in 2008; and notifying the RCMP of information contained in blog posts that appeared in 2019.

The club also stated that it will conduct an independent review of their operations to ensure that they “foster and enforce a culture of zero tolerance for any form of harassment or bullying.”

The North Shore News contacted the Whitecaps for further comment last week and was referred to their prepared statements.

Fighting for safer sport environments

McCormack has been active since her initial blog post, keeping her Twitter feed full of questions and comments from herself and others demanding some action from the soccer world and granting interviews to all who will listen to her story.

In response to the latest statement from the Whitecaps, she replied: “No sincerity, no accountability + many, many unanswered questions remain. ... Not even close 2 good enough.”

When speaking with the North Shore News, McCormack said her goal through all this is not justice for past wrongs, but rather to see changes made to help athletes play the sports they love in a much healthier environment. It shouldn’t take a life-altering blog post for people to start treating athletes properly, she said.

“Everyone has been saying, ‘You’re so courageous. You’re so brave,’” she says. “That’s what I want to change about this. Speaking up and telling the truth and doing the right thing – that shouldn’t be this outlandish thing. That should just be in our culture, where if something is not right, you step up and say something.”

McCormack wants, as a baseline, a system in which players can report inappropriate behaviour without fear of getting cut from a team or losing playing time or suffering any other repercussions.

“My goal by the end of this is that if there’s a 16-year-old in a club getting harassed or whatever by her coach, she knows exactly the protocol, who to go to, what to do with absolute certainty that there’s not going to be any consequences to her playing career in doing so,” she says. “If I woke up a year from now and you told me that’s what came out of all of this, that to me would be spectacular. … The environment that we experienced, I don’t want any other kid to have to go through. It should not be a choice at the elite level to have to decide between your mental health and your safety and being able to play the sport at the highest level. You can be in tough environments and be challenged without going to therapy for five years afterwards.”

Anyone who knows McCormack knows that she won’t be letting this issue die down anytime soon.

“I’ve put my neck out already,” she says. “I might as well just swan-dive with my whole body.”