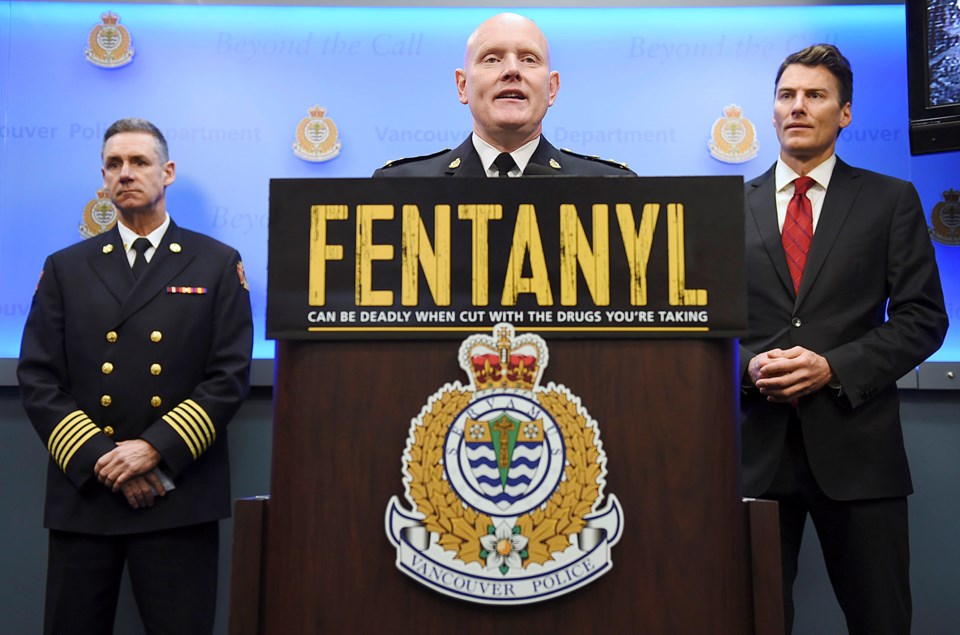

Police Chief Adam Palmer led a unified plea Friday from doctors, politicians and his counterpart at the fire department to pressure the provincial government to provide immediate treatment for drug users who continue to die at a rapid rate in the city.

Beginning a news conference at the VPD’s Cambie Street headquarters on a sombre note that nine people died of a drug overdose in Vancouver Thursday night, Palmer said there is no “treatment-on-demand” for drug users, despite the provincial government’s promise to increase recovery beds.

The need for treatment, the chief said, is at an emergency level as 622 people died in B.C. this year, between January and November, with 124 in Vancouver. The B.C. Coroners Service, which is expected to update the death toll next week, has said 60 per cent of the deaths were linked to the deadly synthetic narcotic, fentanyl.

“Right now, there’s a huge gap in the system and it’s failing those people who put up their hand and ask for help to get clean,” said Palmer, reiterating a statement he made to the Courier in October when asked about the 10-year spike in property crime and how it was being fueled predominantly by drug users.

On a regular basis, he said, drug users approach police and other first responders to get help for an addiction. The chief said one of his veteran officers, Const. Linda Malcolm, attempted last week to get a young homeless heroin addict into detox, but the officer was told it would take nine days.

“Nine days,” Palmer said. “You lose the window to help within hours. Nine days is an eternity. When somebody is ready, they are ready to get off drugs. We need to help them right away, as they are at risk of dying if we do not help them.”

Palmer was joined by Mayor Gregor Robertson, Fire Chief John McKearney and some of the city’s leading doctors on addictions, including Dr. Mark Tyndall, the deputy provincial health officer, who called for more programs where drug users are prescribed drugs as part of treatment. Tyndall warned, though, that some drug users who died this year were taking methadone or suboxone.

“It’s not simply that we can put everybody on substitution [drug] therapy and our problems will be over,” said Tyndall, who also serves as executive medical director of the B.C. Centre for Disease Control. “We really need long term management for people.”

The mayor said he appreciated recent moves from the provincial government to allow unsanctioned injection sites in the Downtown Eastide and set up a mobile medical unit at 58 West Hastings St. He also praised the federal government for its plan to repeal a Harper government era bill that made it difficult, if not impossible, for cities to open sanctioned injection sites.

But, Robertson said, city staff and health authorities estimate 1,300 people use illicit drugs daily in Vancouver and are at immediate risk of overdosing – 1,300 people, he said, who are “playing roulette with fentanyl.”

“Getting a grip on this crisis means that all 1,300 of those people have to have access to treatment,” he said, noting Vancouver has only one facility – The Crosstown Clinic – that offers opioid replacement therapy for 125 people. “We are at wit’s end here. The solution is doable, it’s within our grasp, we can turn this around but it’s going to take dramatic and immediate action from the B.C. government to invest in treatment options.”

Added Robertson: “It’s desperate times in Vancouver and it’s hard to see any silver lining right now when we don’t seem to have hit rock bottom with the number of people dying on any given day from an overdose.”

Fire chief McKearney said firefighters have responded to an unprecedented number of overdose calls this year, including more than 350 between Dec. 1 and 14. He acknowledged Vancouver and the Downtown Eastside is the epicentre of the overdose drug crisis. But, he added, people are dying across the province and that is why the B.C. government should invest in treatment for all communities.

“It’s taken a toll on all responders and the firefighters are certainly seeing the vast share of this,” he said, noting he and the mayor recently went on a ride-along with one of the fire crews. “My perception of what our firefighters were encountering was nowhere close to what they’re actually encountering.”

Late Friday, Health Minister Terry Lake and Public Safety Minister Mike Morris issued a statement on the plea from the police chief and others to fund treatment-on-demand. The statement wasn’t much different from what Lake told the Courier last month when asked about the police chief’s concerns related to treatment.

At the time, Lake said the government was providing more opportunities for people to seek treatment through a range of options. He said the province has increased the number of recovery beds and is on target to have 500 opened in 2017.

The province also spent $5 million to create the B.C. Centre on Substance Use and he noted the federal government has indicated it will help fund more resources in B.C. to help people with substance use and mental health issues.

In the statement Friday, the ministers said: “The overdose crisis is a very complex issue involving many social factors, including housing, public safety, policing, border control, public health, harm reduction and addiction and recovery treatment, as well as legislation that crosses many jurisdictional boundaries. There is no quick and easy solution, but we are taking decisive action across all sectors to do all we can to respond and save lives.”

At the news conference Friday, Palmer said he will know when the government’s investments are working when a person who approaches a first responder -- and requests help to get treatment for an addiction -- will get that on demand.

“That does not exist in any way in our city,” the chief said.

@Howellings