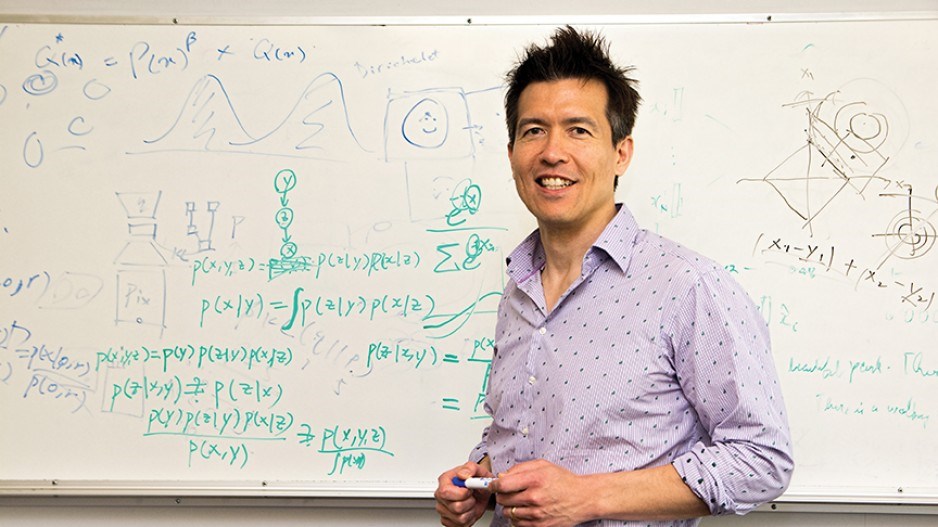

For a computer science professor, Greg Mori doesn’t spend nearly as much time staring at a computer as one might think.

“A lot of what I do is talk to people,” said the director of Simon Fraser University’s School of Computing Science.

It’s fitting, then, that he’s using both his human and his computer skills for his next venture: making computers see and perceive the world as humans do.

Mori is leading the latest artificial intelligence lab within a network of cross-Canada AI labs that the Royal Bank of Canada (RBC) research institute Borealis AI is operating.

The lab, announced by the big bank late last month, will be housed in a downtown Vancouver facility where researchers will be tackling fairness, privacy and bias in AI in addition to its mandate for computer vision.

Mori said this holistic approach of Borealis AI helped entice him to join.

“There’s been rapid progress in many parts of computer vision. Object recognition on your cellphone is something that’s becoming ubiquitous and is quite successful,” he said.

“However, there aren’t the same quantities of data for things such as satellite image analysis for understanding houses, understanding farms, understanding forests.”

Mori, who is heading the Borealis AI Vancouver lab with assistance from University of British Columbia associate professor of computer science Leonid Sigal, said the science of computer vision is still lacking outside the social media and advertising aspects.

“By interpreting visual data, understanding these are houses, these are trees, these are roads, these are particular types of houses, these are particular types of natural settings, we can use that information to make inferences about changes to our world.”

Ahead of the lab’s fall opening, Mori’s immediate responsibility is to recruit talent within Vancouver’s tight technology labour market.

That might prove to be an uphill battle, according to Talentful.ai CEO Jia Chen.

His Vancouver-based company specializes in sophisticated software – powered by AI – to recruit professionals in high-tech jobs.

“We just don’t have enough talent [in Vancouver], and for those who have those kinds of skill sets, those companies cannot afford them,” Chen said.

One of the big problems is that many exceptional young workers that were trained locally migrated to the Silicon Valley soon after leaving school, according to the CEO.

But Chen added that an immigration clampdown in the U.S. has been opening doors to many local tech companies over the past year.

Talentful.ai’s software scrapes publicly available data from websites such as LinkedIn to determine trends and patterns in high-tech recruitment.

Chen said there has been a notable surge in the number of high-tech workers migrating to Vancouver over the past year.

This shift coincides with U.S. President Donald Trump’s tighter immigration and visa measures as well as the implementation of Canada’s Global Skills Strategy.

The strategy went into effect last summer with the promise to process 80% of work permit applications for specialized tech workers from foreign countries within 10 business days. Employers must pay the government $1,000 per position.

But if the local tech ecosystem experiences any recruitment relief in the wake of the Trump administration, Chen said it will be short-lived following Amazon.com Inc.’s April 30 announcement it was adding 3,000 more jobs to the city.

Meanwhile, RBC chief science officer Foteini Agrafioti, who heads the Borealis AI network across Canada, said her research institute is trying to stem the flow of AI experts leaving the country.

One of the primary goals of the institute is to develop intellectual property to commercialize innovations that would help RBC save costs.

But to do that, Agrafioti said, RBC needs easy access to the minds specializing in AI.

“The situation a couple of years ago where we looked at what was happening in academia [wa that] there was all this great research, but we were failing to commercialize a lot of that in Canada,” she said.

Since 2016, Borealis AI has launched labs in Toronto-Waterloo, Edmonton and Montreal, cities considered to be centres for AI research.

“This is really closing the promise that we made two years ago that there will be a place where people will want to go to continue their research after they graduate our top-tier schools across the country, and they don’t have to leave,” Agrafioti said.