Richmond is Canada’s epicentre for a booming, unregulated birth tourism industry emerging from China.

Wealthy Chinese nationals are showing up at local doctor offices, cash in hand, with the intent of giving birth to obtain Canadian citizenship for their newborn babies.

“They are here for that Canadian passport,” said Xi An, the founder of the Vancouver Post-natal Care Association and the owner of the Richmond-based Icy Consulting firm, which helps provide services for women giving birth, including maternity care, arranging appointments and filing various paperwork.

What once was a shadowy, underground practice is now increasingly more open, as dozens of so-called “baby houses” have emerged in the city. Many operators are advertising online, here and in China, that the practice is legal. However, several concerns have emerged related to quality of care, healthcare access and the integrity of the citizenship process.

“We have seen a large growth in the numbers of babies this year who are born here by non-Canadian parents,” An told the Richmond News.

Since the beginning of this year, An’s customers from China have largely outnumbered her local ones (it is common in Chinese culture to hire a caregiver).

According to Vancouver Coastal Health, in the 2016-2017 fiscal year, there were 379 births to foreign nationals at Richmond Hospital. Close to one in five moms (17.4 per cent) entering the maternity ward are not Canadian residents. In 2015-2016 there were 299 births and in 2014-2015 there were 335. From 2004 to 2010 the hospital helped birth, on average, 18 new Canadians per year from non-resident mothers. Nationality isn’t routinely tracked but a tabulation by hospital officials in 2016 showed Chinese nationals accounting for 98 per cent of such births.

Ironically, An attributes this year’s growth to media coverage of a federal petition against birth tourism launched in Richmond last year by community activist Kerry Starchuk.

“Before (birth tourism) was underground, people didn’t know the government’s attitude and only a small group of them were willing to take the risk.

“But after the media’s exposure of the issue, people realized . . . the government seems to be OK with it,” said An.

She noted there is a large demand for live-in, post-natal caregivers, who do not fall under any regulatory framework in Canada. Caregivers are paid from between $7,000 to $12,000 per month to take care of the mother and baby during the 1-2 months after birth. Online advertisements in Chinese show these caregivers provide services such as cooking, but also offer care that falls under what a registered doula or nurse would do, such as lactation assistance.

Some women use baby houses while others go on a “DIY trip,” by renting an apartment locally while giving birth here, said An.

“They usually have friends or family here, who helped them book a two-bedroom apartment in advance.”

Agencies such as An’s also help mothers-to-be book doctor appointments, hospital rooms and car services, as well as apply for birth certificates and passports for the baby.

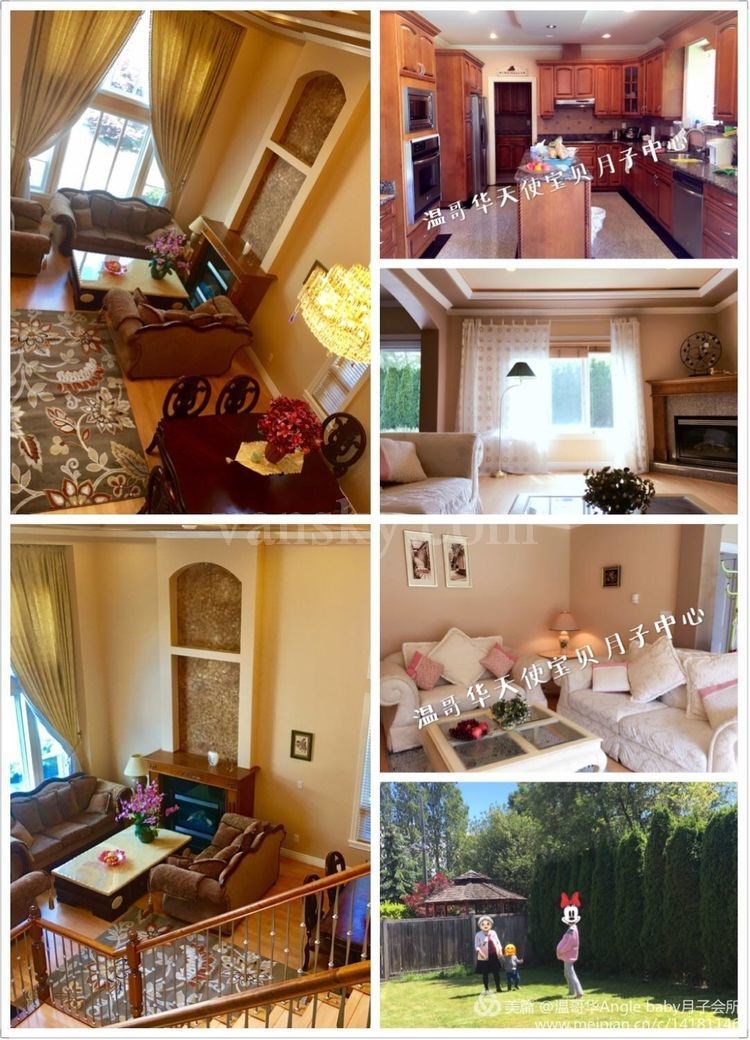

Private homes, or baby houses, are also popping up in Richmond. The News understands one operates on the entire floor of a new residential tower in Oval Village. Others are detached homes. Some don’t have business licenses. Those that do, can operate as tour agencies; and because they provide accommodation for more than a month, they don’t fall under short-term rental regulations.

The News tried to contact several baby house operators, but all either refused to comment or told the News that they were not available.

This month an undercover reporter visited a baby house in West Richmond — a detached house with five rooms. Each room had a bathroom and a crib, and costs $20,000, with meals, over three months.

The operator told the reporter that many moms come here alone since their husband has to work in China. Most husbands can only visit for about 10 days when the baby is born.

The operator also helps the parents arrange doctor visits, usually with Chinese-speaking doctors who are in partnership with the baby houses. Doctor visits cost about $120 each, and are cash only.

One doctor routinely mentioned online is Dr. Brenda Tan, who did not respond to News inquiries. Online comments indicate Tan is very busy with cash customers who are treated “like VIP.”

Citizenship appears to be the number one reason for these clients.

“The parents do it so that when their baby is 18, he or she will have one more option, to choose to be a Canadian or Chinese,” explained An.

She added that the Canadian baby will get a long-term visiting visa to return to China and apply for Chinese ID upon return, which allows the baby to go to school and live in China “like a Chinese” citizen (China doesn’t allow dual citizenship).

“They just have to renew the visiting visa every two years and renew the Canadian passport every five years,” said An.

She said her customers haven’t had trouble having babies here and found it particularly convenient to do so in Richmond.

“Hospitals have Chinese-speaking nurses, and the workers who accept payment speak Chinese, too.

“When they cross the border, they can tell the official that they are here to travel and give birth, and the official has no problems with it.

“If they are OK, then it must mean it’s OK, right?”

According to the newspaper Ming Pao last month, one birth tourism agent, identified as Mr. Liu from LeaderBB, said he expects upwards of 10,000 birth tourists in B.C. from China in the next three to five years if stricter regulations are not implemented by the government.

Liberal-Conservative divide

The Liberal-led Canadian government and official opposition Conservatives both agree birth tourism is not acceptable. However, they disagree on what action should be taken.

“I think it is a problem. The question is, what is the scope of the problem?” said Liberal Steveston-Richmond East MP Joe Peschisolido. “You could be seeing the development of a pipeline bringing folks in, and if that’s the case then it’s a huge issue.

“You’re getting an organized international effort to abuse the system and subvert the integrity of the immigration system.

“You have guys looking at loopholes, looking at our generosity and abusing it,” he added.

Peschisolido said the government is monitoring the situation. He said one solution could be better enforcement at the border and also education, by way of sending other countries a message.

“It’s not a friendly message. It’s actually an educational one. Don’t do it, we’ll stop it and there will be consequences,” he said.

Richmond Centre Conservative MP Alice Wong backed Starchuk’s petition to end jus soli (place of birth) citizenship rights. It was dismissed by the Liberals last year.

Canada and the United States are the only developed countries that offer automatic, no-strings-attached citizenship from birth.

“This is a growing problem that will only get bigger if we don’t do anything about it,” said Starchuk.

Such a change to the Citizenship Act would be applied across the country and end a right Peschisolido finds virtuous.

“If you’re born here, you’re Canadian; that is a good thing. We have to be careful in fixing the problem,” he said.

But Wong said enforcement is difficult and, to date, the Liberals haven’t found a solution to what she calls a “totally unacceptable” industry that is impacting local neighbourhoods.

“The best thing is to go with the root of the problem. This has become a big money-making industry that does no good to society. It’s unfair and it abuses the system,” said Wong.

“We have to go to the [other] route. The best way is to make it just like Hong Kong or Australia . . . You have to prove at least one parent is a permanent resident or a Canadian so the baby gets citizenship,” said Wong.

Birth visits all but formally legal

Richmond-based immigration consultant Ken Wong sees the loophole as a threat to the immigration system’s integrity.

“Yes, I think it dabbles into violating the integrity of citizenship privileges,” said Wong.

“These kids won’t contribute to Canada. They’re a passport owner but will spend their life elsewhere,” said Wong.

He noted that once a baby is born at Richmond Hospital, that baby is a Canadian. As such, if there are costly health complications the baby would have the right to be treated under the publicly-funded Medical Services Plan.

He describes birth tourism as a process that is grey in nature, with few clear lines of interpretation.

“There is not a section in immigration law that says birth tourism is illegal,” said Wong.

CBSA spokesperson Robin Barcham confirmed to the News “there is no specific reference in the [Immigration and Refugee Protection Act] legislation regarding women who are pregnant, therefore pregnancy in itself is not a reason for inadmissibility.”

However, Wong said Canadian officials can deny a visa by reasoning that the woman may not be able to return to China due to health considerations.

And so, in order to be guaranteed entrance, it is thought that many women are not declaring their true intention. Instead, they state they are tourists, but it just so happens that they’re a few months away from giving birth and have booked a baby house or apartment. Such misrepresentation is illegal, according to Barcham.

“Several factors are used in determining admissibility into Canada, including: misrepresentation, health or financial reasons,” said Barcham.

But, in such cases, proving a woman has come to Canada for the exclusive purpose of giving birth to obtain citizenship is difficult, said Wong, adding “there’s no way, in my opinion, that CBSA can enforce it.”

He said CBSA could theoretically raid baby houses and obtain booking records.

“This could be low on the list of priorities. I do think there’s a difference between drug trafficking and this,” said Wong.

He noted the practice of having a baby in Canada is likely for the child only, however it is possible that the child can eventually sponsor the parents’ citizenship process when he or she turns 19. That said, the child would need to establish a Canadian income that could support the parents. Or conversely, said Wong, the family could have lots of money.

Nurses speak out

The News has spoken to several workers at Richmond Hospital who are dismayed by what is occurring inside the maternity ward from a health care perspective. No one would speak publicly for fear of disciplinary action.

B.C. Nurses Union acting president Christine Sorensen said the union is aware of longstanding concerns being expressed by nurses at the hospital.

“There are certainly concerns about patient safety, workload and access to healthcare,” said Sorensen.

First and foremost, she said nurses are concerned about the health and well-being of moms and babies, both foreign and Canadian.

“We’re concerned about mums and babes being diverted to other areas or hospitals or receiving care that is not the quality or standard they should expect as a Canadian because space is being utilized for foreign nationals. Our publicly-funded hospitals should be for the Canadian public,” she said.

Furthermore, “who is providing supports to these foreign nationals? I’m not sure who does follow-ups. As a community nurse this concerns me. The mom may not know or understand or identify complications happening,” said Sorensen.

According to hospital records, the non-resident maternity patients spend one less day in the ward (2.2 days for residents compared to 1.2 days for non-residents).

Sorensen said financial considerations are likely outweighing health considerations.

“There’s a lot of changes that are occurring in the first three days for both mom and baby” and proper medical monitoring is essential before discharge.

While Richmond residents receive follow-up care, foreigners do not.

“I’d be cautious that there’s no indication that these [baby houses] are providing for regulated, registered care at any level,” said Sorensen.

“It puts the nurses in a difficult ethical dilemma,” she said.

Meanwhile, nurses are also questioning access to the hospital for locals.

“With most hospitals, you have to live in the hospital’s area. Are they altering this process to cause families that should deliver in Richmond to go elsewhere, to take patients who are paying? We’re wondering.”

Vancouver Coastal Health (VCH) maintains being bumped for any reason is very rare (less than one a month, on average). However, a mother who is stuck in a waiting room while in labour or sent to the ER wouldn’t show up on transfer data.

Quality of care may be compromised, said Sorensen.

“The nurses report to me they have increased workload because of the additional moms and babes they’re seeing.”

Sorensen said she would hope the fees collected go back to the ward. Presently, fees go into general revenue, but VCH officials have maintained the ward is adequately served.

Birth tourism subsidized

As of 2016, the hospital asks non-residents to pay a $7,500 deposit for a regular birth and $13,000 for a C-section birth.

In Vancouver, B.C. Women’s Hospital officials bar foreigners from registering to give birth at their hospital. Meanwhile Richmond has a registration process open for foreigners.

Fees are set annually by the Ministry of Health on a cost-recovery basis. According to a Ministry spokesperson, such fees do not account for things such as the capital costs to build new hospitals (Richmond needs a new acute care tower) or the countless hours public officials and communities have put in over the decades to build a safe and regulated health care system.

When asked about what she thinks about the criticism against foreigners taking up local public resources, An said: “I don’t know, but the hospital decides that price and the parents pay the price, so does it count as taking up resources? I don’t know.”