As part of the Courier’s 2003 series on religions, big and small, Michael Kissinger investigated the controversial Church of Scientology and paid a visit to its downtown Vancouver location where he received a tour of the premises, talked to supporters and even took one of their personality tests.

Originally published March 30, 2003.

***

When James Wood moved to Vancouver seven years ago, he was a 24-year-old pothead. He hated people and rarely kept in touch with his family, even though they lived just around the block from him in Toronto. He came out west in search of B.C.’s infamous bud and maybe a job. Instead, he found Scientology.

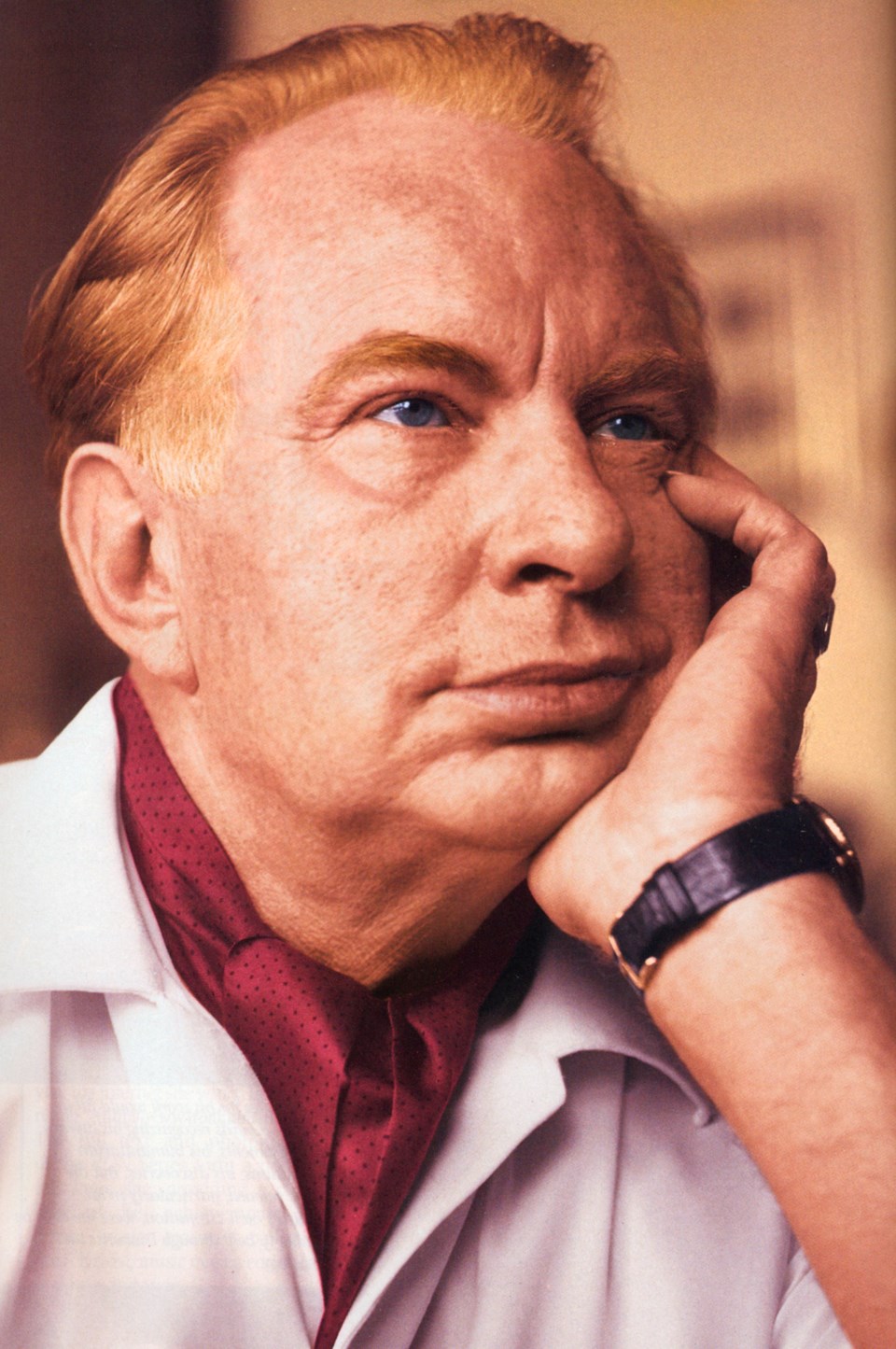

Since it was created by world traveller-cum-science fiction writer L. Ron Hubbard in the 1950s, Scientology has remained a relatively small, if controversial, player among world religions, best known for high profile followers such as John Travolta, Tom Cruise, Lisa Marie Presley, Isaac Hayes and Nancy Cartwright — the voice of Bart Simpson.

In Vancouver, the Church of Scientology has occupied the corner of Hastings and Homer since 1980 — it incorporated as a church in 1971 — with volcano-adorned window displays of Dianetics (the book that started it all) and signs beckoning passersby to drop in for a free personality test.

That’s what James Wood encountered two weeks into his hazy west coast sojourn, when he found himself jobless, with plenty of time on his hands and broke from spending all his money on pot.

“I happened to walk by and saw the sign and said, ‘Oh god, it’s a church, I hate church,’” says the affable 31-year-old. “Then I went to the library to prove Scientology wrong, to read one of their books and say, ‘Well these guys suck’ — like everything else I had ever read.”

Much to his surprise, Wood agreed with everything he read in A New Slant on Life — a collection of Hubbard’s essays on family, children and the state of the world.

“I read the book in something like two hours and said, ‘Oh my god, they think the same way I do.’ I had this cognition that it’s OK to think the way I do, and that I should probably hang out with people who had the same viewpoints as me. So I walked in and said, ‘How can I get involved?’ And some guy said, ‘You can work here.’ And I’ve been here ever since.”

Wood says that since immersing himself in Scientology and the teachings of L. Ron Hubbard, he no longer uses drugs, he understands how to communicate better and his relationship with his family has improved tenfold. He’s also gotten married and now has a son.

“In the beginning, it gave me something to do and something that I thought was true. And now, the more studying I do and the more I use Scientology, it just makes sense. It gives names for things in life that you probably already know about, but sometimes it takes a guy writing a book about it to smack you in the head.”

Cleared for takeoff

The book that seems to have smacked the most people in the head is Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health. Published in 1950, Dianetics was Hubbard’s explanation of what makes people tick. He postulated that humans possess an analytic mind and a reactive mind — the part of the mind that acts unconsciously and causes unwanted sensations, emotions and psychosomatic illnesses. Dianetics is essentially Hubbard’s prescription for how to “clear” one’s reactive mind. This is done through a technique called auditing, where someone trained in applying Dianetics and/or Scientology processes assists a “preclear” to defeat his or her reactive mind.

To do this, an auditor uses a contraption known as an Electropsychometer, or E-meter, resembling two soup cans wired to a miniature dashboard, that’s designed to help an auditor locate areas of spiritual stress or travail in a preclear’s life or even past life. When subjects are talking about painful events while holding the cylinders, the E-meter registers that distress through a small electrical current.

Originally, Hubbard didn’t intend to incorporate spirituality into Dianetic therapy. In fact, by all indications, Hubbard had considered his theories on mental health to be strictly a science, albeit one that stood in stark opposition to the views of the psychiatric community, which dismissed him. But by 1954, Hubbard had established the first Church of Scientology in Los Angeles. Some critics claim it was for tax purposes, while others say it was a natural response to the spiritual discoveries that were being made through Dianetics.

A key component to Scientology is the belief that “man” is a spiritual being or “thetan,” and by going through different levels of spiritual counselling — auditing sessions, seminars, courses, becoming an auditor and so forth — a person can gain spiritual awareness.

A metaphor frequently bandied about is that of a bridge. The goal of Scientology is to work your way up The Bridge, through the various stages of enlightenment, known as “the eight dynamics,” towards a state of complete spiritual freedom or OT (Operating Thetan).

While Scientology believes in a supreme being, it doesn’t dictate who or what that supreme being is. It’s up to individuals to decide as they become more enlightened.

Enlightenment, however, doesn’t come cheap.

One of the first steps for anyone wanting to move up The Bridge to a state of “clear” and beyond is the Purification Rundown — a regimen of vitamins, minerals, exercise, rest and sauna time (most churches have their own saunas) to rid the body of toxins, pollutants, alcohol and drug residue that apparently block mental and spiritual development. In Vancouver, the Church of Scientology’s purification program costs $1,609.87, as indicated on one of its many promotional posters.

Then there’s the cost of the seemingly endless stream of L. Ron Hubbard lecture CDs, workbooks, courses, training programs to become an auditor, buying your very own “Super VII Quantum E-meter” — all of which can add up to thousands upon thousands of dollars in expenses, with the promise of faster progress up The Bridge. “Soar to OT,” announces an advertisement in one of Scientology’s many promotional magazines. “Your fastest route to Clear and OT starts here,” claims another.

While these might be necessary costs to moving up The Bridge, they’re not compulsory to being a Scientologist argues Wood.

“To be a Scientologist just means that you use Scientology technology to improve conditions in yourself and those around you. I have guys who have never done a course here. They just keep buying the books and applying the things they read to their lives, which is fine... The basic courses to find out about Scientology and different areas of life are anywhere from 45 bucks to 150 bucks. You can go out and buy Anthony Robbins cassettes and ‘improve your mind’ and ‘wake up all energized’ for a grand.”

Wood, like the rest of the staff at the Church of Scientology, receives training, lectures, workshops, and reading material for free in exchange for the work he does. Wood’s job entails talking to the public, answering questions about Scientology and explaining the results of the personality test to anyone who takes it.

After filling out the 200-item questionnaire, which includes such probing questions as, “Are you a slow eater?” and “Would you make the necessary actions to kill an animal in order to put it out of pain?” Wood kindly informs me that I am fairly happy — but not to the degree I want to be — nervous or over-excitable, critical of others, either verbally or mentally, and pretty withdrawn.

As he tells me this, I find myself fidgeting with my hooded sweatshirt and mentally noting that Wood’s earrings are far too big for the size of his head.

“It’s really up to the individual if they want to do something about it,” says Wood. “Say for instance your nervousness. If you really wanted to get a grip on that, we have courses that address these areas of your life.”

World according to Ron

Despite being nervous and withdrawn, I somehow muster up the courage to take a tour of the premises with Angela Ilasi, the church’s public relations officer.

Raised by Scientologist parents, Ilasi, who is 22 and has been working at the church for three years, says Scientology has helped her understand the mechanics of life. “The biggest thing is to be able to see situations in life for what they are, not what they appear to be... Instead of just going through life all confused and not knowing what’s happening at all, I feel like I’m more in control.”

Ilasi says that on a basic level, Scientology teaches people how to communicate better and have healthier relationships. “It’s practical and very much about improving your life, and then as it goes up, it gets more into the spiritual realm.”

As Ilasi walks me through the church, I notice that nearly every room has a framed photograph of L. Ron Hubbard, usually in an ascot or a captain’s hat, often looking wistfully out at the ocean or standing on the bow of a ship.

Everyone at the church refers to Hubbard, who died in 1986, as “Ron.” Coincidentally, it’s Ron’s birthday the day I visit the church. There’s even a poster in the lobby inviting people to celebrate “man’s best friend” at Moxies for a birthday party the following Saturday.

As in most churches, there’s a chapel where a minister leads Sunday sermons, naming ceremonies, weddings and funerals.

Downstairs, there’s a sauna, auditing rooms and classrooms. In one of the rooms, a man and a woman, both training to be auditors, sit and face one another in silence.

“They are practising being able to confront,” Ilasi whispers. “They’re practising being able to comfortably be in a space without bothering you. Later as it gets higher to where people are yelling at you, you practice keeping it together.”

I’m then led back upstairs to a neatly kept office with a large viewing window and a velvet rope cordoning off the entrance. The unused office contains seafaring memorabilia, an up-to-date calendar, a bookshelf filled with some of Hubbard’s thousands of books and lectures, and a desk. On the desk, a handwritten note, as if scribbled by the man himself, is positioned casually.

Ilasi says the office, which can be found in every Church of Scientology, is a tribute to Hubbard and a symbolic gesture that in whatever port or town he happened to travel, he’d always have an office where he could sit and work.

Critical mass

Like most new religions, Scientology began during a time of great societal change and growing disenchantment with established religions. It also had a charismatic leader whose ideas seemed new, but not unfathomable.

“Hubbard was really quite clever in that he put together a lot of ideas that are very popular these days in pop psychology,” says Linda Christensen, a lecturer in Comparative Religion at UBC. “He was talking about these things ahead of his time in terms of getting clear of all your past hang-ups. But because pop psychology is so widespread, it seems to me his ideas aren’t that novel anymore.”

What really prevents Scientology from spreading, however, is the financial factor, she says.

“Let’s face it, it costs a lot of money to take all their courses, so it’s something that really can succeed only amongst the rich or those who are gullible enough to spend their money on it... It’s more a question of what’s going to happen a hundred years from now. When you look at world religions, they’ve been around for a couple thousand years, so this is just a tiny drop of time.”

Dr. Stephen Kent, a University of Alberta sociology professor specializing in the study of religion, says the information superhighway has also hindered Scientology’s expansion into the mainstream.

“The Internet seems to have caused a problem for Scientology. People who might be interested in the organization can log on and find out a lot of material by the organization itself, but also a tremendous amount by its critics. So the Internet has inhibited Scientology’s ability to control information on itself.”

One of the church’s most vocal critics is Gerry Armstrong, a former Scientologist who calls himself “Scientology’s Salman Rushdie.” Armstrong left the church in 1981 and has dedicated his life to speaking out against what he frequently refers to as a “psycho cult.”

When I first contacted Armstrong, who recently moved from Chilliwack to Germany because of that country’s strong stance against Scientology, he expressed concerns that I might be a Scientologist posing as a journalist. In my half dozen email exchanges with him, he replied from a different address each time. He claims to have been sued six times and harassed by the church for breaking a legal contract preventing him from speaking publicly about Scientology, an agreement he says he was coerced into signing.

“My goal is for every Scientologist or ex-Scientologist to be able to speak freely about his experiences,” says Armstrong. “I was lured into Scientology the same way everyone else is — by its false promises. The cult promised to raise IQ a point per hour of ‘auditing.’ It promised stable psychological states — ‘Clear’ and ‘OT’ — far above what man has achieved before. It promised superhuman abilities... I bought the package.”

Even calling Scientology a religion is controversial. “Since the KGB and mafia are not considered religions by thinking people, neither is Scientology,” says Armstrong.

According to Linda Christensen, however, Scientology is a religion. Oddly enough, the term cult isn’t that far off either, though it often gets used in the media to generate what she calls a “scare image that’s rooted in fear.”

“In academic circles, the term cult is a technical term for a particular type of religious institution. A cult is a small movement, not quite that well established and organized yet, like the beginnings of a religion. And because it’s small and new, it’s on the fringes of society… so in a sense Christianity began as a cult. Most religions begin as a cult.”

Besides the much-used “C” word, if you click your way through Armstrong’s web site — which includes the sound of a cash register whenever a new page is opened — or peruse other colourful anti-Scientology sites (which many Scientologists consider “hate sites”), you’ll find accusations of brainwashing, deception and corruption.

The movement’s abstinence-based drug rehabilitation program Narconon, which claims to be withdrawal-free, has also been criticized.

More worrying, the sites contain frequent references to followers who’ve died under questionable circumstances while in the care of Scientologists, as well as the 1991 Time magazine cover story detailing the conviction of 11 high-ranking church officials (including Hubbard’s wife) in the early ’80s for “infiltrating, burglarizing and wiretapping” private and government agencies in an attempt to block investigation of the church. All of which has made Scientology particularly vigilant about its public image.

“Scientology can be very aggressive against perceived opponents,” says sociology professor Stephen Kent, who himself has been a target. In 1998, after Kent spoke to German government officials who were gathering evidence against Scientology, the church paid for an advertising insert in the Globe and Mail in which he was compared to Holocaust denier Ernst Zundel.

“There’s a big difference between criticism and making up strange lies and promoting it,” says Angela Ilasi. “If somebody honestly understands Scientology and says, ‘Well, it’s something I don’t really agree with,’ I have no problem with that.”

According to James Wood, Scientology’s critics are actually quite small in number. “You might find 10 web sites that say something negative about Scientology. But out of those 10 web sites, it probably totals 50 people in all of North America.

“The hardcore guys will probably never accept it because it’s denominational of all religions. We don’t have a set belief system; we leave it up to the individual… People come in here all the time and ask us about God and everything else. It’s OK. I’m not against anything you do. In fact we embrace it. Just read a book, quit trying to pick a fight.”

Kent’s assessment of Scientology, however, is less favourable.

“Scientology is a multidimensional, transnational organization, only one part of which is religious… Scientology would like to replace conventional mental health practices with its own techniques, but most Scientologists have no scientific training, which makes their ability to offer intelligent criticisms somewhat limited. From time to time, Scientology has helped uncover mental health abuses, but much of what it claims is shrill.”

Still, there’s obviously something about Scientology and its prolific founder that rings true for followers and employees. Just talking about Scientology puts a smile on Ilasi’s face. “One of the biggest misconceptions is that we’re secret, but I try to put our books in as many libraries as possible. The front of our building is all glass. You can come right in and ask us questions. So it’s very un-secret. We like to tell people about Scientology because we have such a good time and we want people to know about it.”

Whether spreading the word about Scientology will increase its chances of being accepted by the mainstream or simply add to the list of detractors remains to be seen.

“We don’t really feel on the fringes,” says Ilasi, standing under the watchful gaze of L. Ron Hubbard in his fetching ascot and captain’s hat. “When I read about Scientology in the media, it seems like we’re on the fringes... so I guess we’re still kind of getting known. I think most people know the name, but they don’t know what the deal is.”