Ask Squamish Chief Ian Campbell what he thinks about global sea level rise, and he’ll tell you that it’s something his ancestors have already lived through.

Based on the oral teachings passed down to him from his grandfather, Campbell can almost picture the “great floods” that might have covered the land thousands of years ago.

“Growing up, I really thought that what I was learning was matter of fact, that everyone had access to this information,” says Campbell.

Campbell – who had been in court challenging the Kinder Morgan pipeline just prior to our interview – says he wants the history of how the Squamish dealt with sea level rise to become common knowledge.

It’s possible that the great floods Campbell is referring to are linked to the melting of ice sheets or glaciers at the tail end of the last Ice Age.

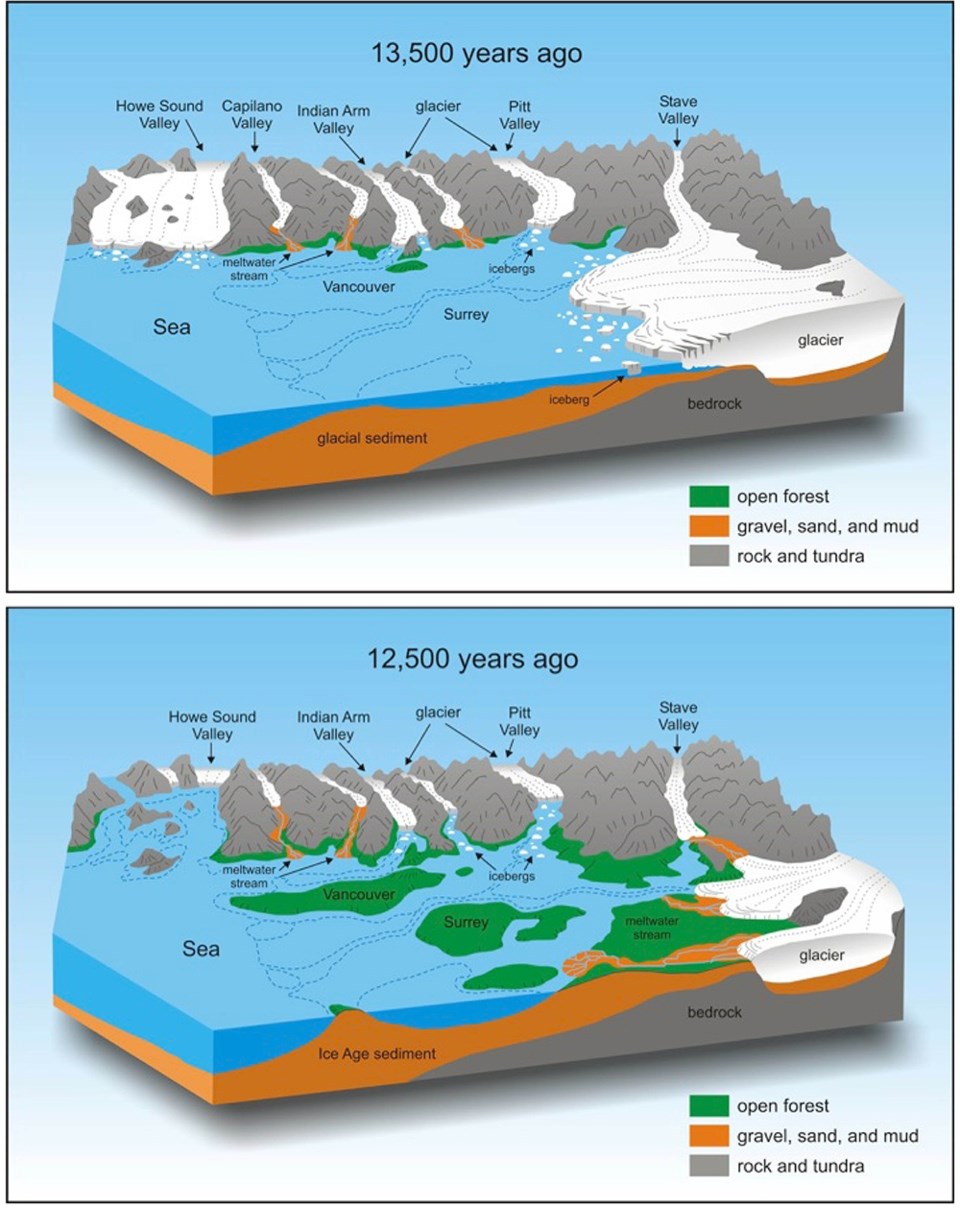

John Clague, professor emeritus of Earth Sciences at SFU, says that, during the last Ice Age, the Lower Mainland was submerged below sea level, weighed down by thick ice sheets. “As the ice disappeared over the land 12-13,000 years ago, the land rebounded. It bobbed back up like a cork in water,” he says. “As it did, the land eventually rose, what is now the Fraser Valley became land area, and that’s the time I think First Nations people first occupied parts of the Fraser Valley.”

Although not yet published, Clague says his latest research indicates that there was a “monster flood” in the Lower Mainland about 12,000 years ago, when a glacier-dammed lake emptied suddenly, sending a flood of water down the Fraser Canyon. At that time there weren’t any glaciers left in the Fraser Valley, but some still existed further inland. His research indicates that, during the time of the flood, the deepest parts of the Fraser River would have been 152 metres (500 feet).

“Most peoples prior to the Industrial Revolution have tales of flood ... The biblical flood is an example. One has to be a little careful about linking it to some specific event in the past, but, having said that, I’ve been doing some work on a ‘huge flood’ that came down the Fraser Valley” during a time when Indigenous people would have inhabited the area.

Returning to Indigenous oral history, Campbell relates that “sea levels rose drastically … flooding out most of the coastal peoples, and many people perished. Populations were decimated and a handful of our people survived by going to places like [Mount Garibaldi] to find safe haven.”

After his grandfather passed away, Campbell says he continued learning from other local elders, including the Musqueam, who relayed similar stories about landscape-altering floods.

According to Squamish knowledge, the great floods happened as a result of selfish behaviour. “The young people turned their backs to the old laws, and they weren’t listening, they were wasting, they were greedy,” Campbell says. “Our people were exhausting resources like sea lion colonies, elk herds, different things and they weren’t sharing them.”

Elders warned the young people that they needed to take care of each other, but the young people persisted in their ways, and then came the flood.

“The medicine people would then pray and mark some sticks with ochre, and that would stabilize the water for a while," says Campbell. "But the young people would [continue to] turn their backs on the old way and the water would then breach and continue rising.”

With so much land under water, the Squamish people gathered on three major peaks – Garibaldi, Mt. Baker and Icecap Peak (near Lillooet) – says Campbell. The waters were rocky, with strong currents. Canoe groups would get separated easily, fish stocks were unreliable and food was scarce. “... Over generations they were traumatized,” he explains, “and they had to re-establish themselves once the water receded, and we had to repopulate the areas.”

Campbell says that not everyone believes the story that was passed down, but even non-believers can understand it as a cautionary tale.

“It’s an oral tradition which recounts the values and the principles and the structures that were necessary for us to survive those major events,” he explains.

According to Clague’s knowledge, gathered through Western scientific research, “in the post-Ice Age world, you do get huge floods on the Fraser River, and maybe one of those floods over the past 10,000 years ago was so big, so unprecedented, that it was actually what the oral traditions [such as Campbell’s] are referring to.”

One of the important takeaways, says Campbell, is that population growth is cyclical, that everything changes, and that people must adapt.

Adapting, of course, is what a coastal city like Vancouver will have to do.

Scientists at both the provincial and federal level have conducted extensive research on sea level rise. According to Environmental Reporting B.C., the sea level has risen an average of 3.7 centimetres in Vancouver between 1910 and 2014. Looking ahead, a report from Natural Resources Canada projects Vancouver’s sea level to rise 60-70 centimetres (roughly two feet) by 2100. However, Christian Schoof, a UBC professor in the Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, says that by 2100 we can expect “a metre of sea level rise” or more due to “significant uncertainty” over how the Antarctic ice will respond to climate change.

On a municipal level, the City of Vancouver has been preparing for sea level rise for several years. However, the majority of its plans have focused on the technical aspects, using modelling to simulate storm flooding and mapping which areas of the city will be affected by sea level rise.

Brad Bedelt, assistant director of sustainability, says the city will begin community and neighbourhood consultations soon. Last month, the city met with members of the Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh nations to share research findings and discuss how they can partner effectively in addressing the coming changes. (Bedelt says the city hopes to meet with Squamish Nation soon.)

“[It was about] getting some of their thoughts as to how the city can respond to sea level rise, and then really identifying how we can work together going forward. We know this is going to be years of work together,” Bedelt says.

Westender reached out to the Tsleil-Waututh and Musqueam nations to hear their perspective, but interview requests went unanswered. However, Campbell says that, in partnering with governments to address sea level rise, he wants to see a nation-to-nation relationship. The fact that Vancouver’s First Nations reserves are close to the water makes the need for a strategy even greater.

Sea level rise consultant John Englander says there are a number of ways to respond to changing sea levels, including constructing buildings on stilts or concrete pilings, erecting flood protection walls, building on floats and, finally, large-scale retreat – in which people move away from the coastline. Due to the price of land in Vancouver, Bedelt says retreat isn’t the city’s preferred option. Neither is building concrete flood walls. “It’s difficult to move people away. In Vancouver, we don’t have a lot of space as it is, and the value of land here is so high that retreat is a difficult option here … So, at the moment, we’re looking at ways to protect or adapt our neighbourhoods,” he explains.

One option the city is considering is to convert hard-walled shorelines to a more natural shoreline, with flood protection embedded in the landscaping. As Bedelt describes it, this could mean replacing hard, vertical seawalls with a specially engineered shoreline that slopes downward to ease wave action.

“Right now, the seawall around False Creek has quite a … hard-wall edge to it, which has served us well for nearly a century,” says Bedelt. “But a more natural approach would take that hard edge and replace it with an edge like you might see in parts of Stanley Park, where you’ve got the coastal tide pools and the benching, replacing the kind of hard infrastructure edge with a more natural shoreline.”