The city is approaching an anniversary that doesn’t call for celebration.

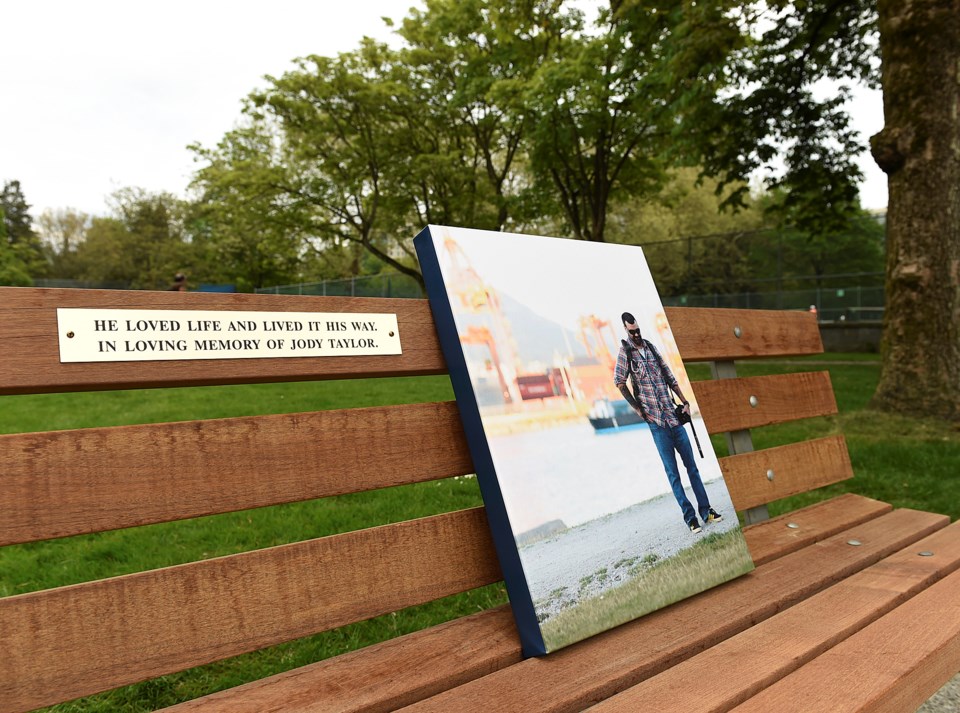

On March 31 last year, park board employee and arborist Jody Taylor died while cutting back a caltalpa tree in Connaught Park. He was 43 and father to a 10-year-old daughter. The nature photographer and hard-core rock singer is publicly honoured with a commemorative bench in Stanley Park along with a maple tree, still a sapling, that grows nearby.

The park board responded to his accidental workplace death in another important way. They are putting more emphasis on safety training and practices for the 53 urban foresters and additional apprentices who work within an industry widely considered one of the most dangerous in the country.

“I never really understood why we put so much emphasis on safety until I experienced this incident. It really hit home why we work to be safe,” said Tatton Zanardo, the first person to hold a new park board position as the urban forestry safety and training advisor. The role was created after Taylor’s death.

“There are so many variables in our trade and we try to mitigate the hazards as best as we can. Unfortunately, this is what can transpire,” he said. “In British Columbia, we have standards and training that is second to none.”

The chairman of the park board said the death was felt by all commissioners and staff, and the work of arborists is vital to a leafy city like Vancouver.

“It is an important safety position that we needed to bring in, especially as we try to create a larger urban canopy.” said Michael Wiebe.

High-risk livelihood

According to WorkSafeBC, 94 forestry workers died on the job in B.C. over the past decade between 2006 and 2015, peaking in 2008 with 18 deaths in a year there were 225 across all industries.

In 2015, WorkSafeBC recorded 50,000 missed work days because of on-the-job injuries in forestry. In the primary resource economy, that compared to 30,000 work days lost in agriculture, 17,000 in fishing and 15,600 in oil, gas and mineral extraction.

The highest number of missed work days came in construction with 315,000 and health care or social work with 353,224 days missed because of workplace injury or violence.

For nearly a decade, Zanardo worked as a utility arborist for a large forestry company, clearing trees and brush around electrical poles all over the province. He said the safety measures at Electrical Industry Training Institute were comparable to those at the park board and part of his new responsibilities include implementing additional training and certification through EITI.

In his new role as a safety training advisor, Zanardo is requiring additional certification requirements for park board arborists and is standardizing the crew’s equipment and updating the training manual as well as holding monthly meetings and audits with the teams.

“We basically are going over and above what the industry is doing. Everything we were doing was in compliance but now we want to become the industry leader when it comes to urban forestry safety.”

Workplace PTSD

Hired as an urban arborist in February last year, Zanardo didn’t have a long history with Taylor, but described him as a passionate photographer who loved to be in nature and cared deeply for his daughter.

He was part of the secondary grounds crew that came to assist on the day Taylor died. He said the fatal accident was life-changing and is now a driving force behind his commitment to workplace training and safety.

“Forestry is the most dangerous trade in the world. The stuff we are dealing with is not engineered, it’s nature. If we could predict nature that would be amazing, but it’s not reality.”

Taylor was killed by what’s known in the industry as a “barber-chair,” which means the branch he was trimming unexpectedly split vertically before it fell and crushed him. The four witnesses to the fatal accident have all sought trauma counselling, said Zanardo, adding that speaking to a counsellor with Vancouver Fire and Rescue Services has been particularly beneficial.

“Family and friends have been supportive. There has been a lot of stress, some anger and resentment, the natural things that come from experiencing something like this,” he said. “Whether there are flashbacks or it’s just a bad day, it’s not uncommon that we have that.”

Irreversible change

Sarah Kirby-Yung was the park board chairwoman at the time of the fatality. She said the weight of the workplace death was felt deeply by staff, management and commissioners.

“You feel that responsibility very seriously when it happens under your tenure, so to speak,” she said today.

Kirby-Yung spoke at Taylor’s memorial and a private funeral amid his friends, family and young daughter, Tristen. The commissioner empathized deeply with the little girl since she also suffered the loss of her father when she was a teenager.

“I was twice as old as Jody’s daughter, and I remember that feeling very well, when someone leaves a young family behind. Tristen and Jody were very, very close and had a strong father-daughter relationship, which was fortunately what I also had with my dad,” said Kirby-Yung.

“When you see that little girl looking up at you and you remember what it’s like, it’s pretty tough. You feel it again because it never goes away when you go through that yourself.”

Her father died suddenly of a heart attack, a terrible shock that remains painful.

“Dad does what he does and then does not come home at the end of the day,” said Kirby-Yung. She had just turned 17 and expected the upcoming anniversary to be a difficult time for Taylor’s daughter.

“It’s always hard at a time like this when it’s one of the firsts – the first year, the first birthday, the first holiday, the first Christmas or whatever it is your family celebrates. Everybody goes back to their lives but your life is irreversibly changed.”

Memorials

Before Taylor’s death, the previous city worker to die on the job happened in 1997 when an engineer was struck and killed by a passing vehicle upon exiting a maintenance truck.

The Second Narrows in Burrard Inlet is also the site of one of the highest profile workplace tragedies in Canadian history. After collapsing in 1958, the Ironworkers Memorial Bridge was finished and named in honour of the 19 labourers killed on the job.

A plaque to the right side of the north doors of City Hall recognizes city employees who have died at work. The plaque was installed in 1993 on April 28, now a national day of mourning known as Workers’ Memorial Day. On April 28 last year, the park board planted a maple tree in memory of Taylor and have since installed a bench nearby.

The park board will receive another memorial in the coming weeks. As a show of support for Taylor’s crewmates, they will receive a large wood carving of an eagle’s head. It was made by Zanardo’s father, a high-voltage electrician, who chose an eagle for the animal’s majesty and West Coast symbolism.

“He wanted to make it for our team to commemorate the loss of one of our colleagues,” said the son. “It hit close to home as well with me being in the same trade. It could have been me or anybody else that day.”