The five-year-old boy tugged on Sandy Teel’s sleeve.

Why, he asked, did she give a hug to other children in his kindergarten class every morning?

Teel had noticed him before, standing by himself in the school’s morning line-up, and smiled at his curiosity.

She explained that she ran a daycare and that, when she dropped the older children off at school each morning, she gave them a hug because their moms and dads were at work. She wanted them to know they were loved and cared for.

“Could I have a hug, too,” the boy asked.

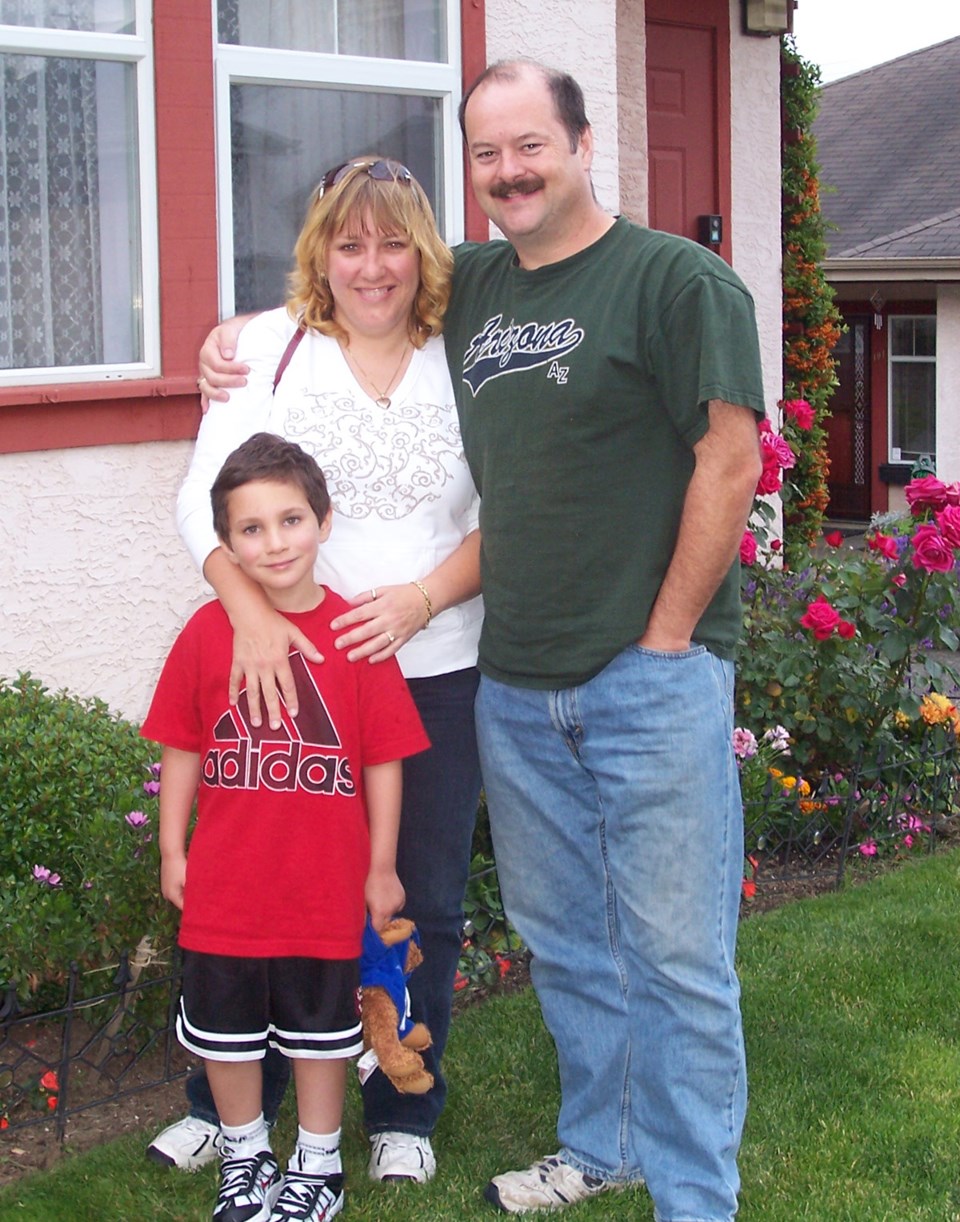

One year later, that little boy became Sandy and Mark Teel’s son.

Andrew Teel entered the foster care system early in his life. He was moved from foster home to foster home, sometimes as many as three times a month. By the age of five, he’d already had many bad experiences.

He wanted what all the kids around him had — someone to not only give him a hug every morning but also to hug him when he got home.

Sandy didn’t know any of that, not at first. She just thought he was a shy kid whose parents weren’t able to be there for him. Every morning she gave Andrew a hug and every night she spent the dinner hour telling her husband and 17-year-old son Darren about this sweet little boy at school who, she had learned, was in foster care.

“You talk about this kid all the time,” Darren said after a couple of weeks. “Why don’t you adopt him?”

Sandy and Mark were floored. Ever since they had learned that Andrew was in foster care, they’d had the idea — just a whisper, really — of adopting him . But they had worried how Darren, after 17 years of being an only child, would react to having a younger brother.

Darren, they discovered, thought it was a no-brainer. He knew his mother already loved Andrew and that Andrew needed a family. “If he doesn’t have a family,” Darren said, “we should bring him into ours.”

For privacy reasons, the Teels could not be told whether adoption was even a possibility. Sandy wrote an email to family services to float the idea but it took her three days to hit “send.”

“To me it was, ‘If they say he’s available for adoption, can I be the parent he needs me to be,’” she says of her hesitation.

For his part, Andrew says, “The moment I saw [Sandy], I knew she would be my mom.”

Asked why, Andrew — who is now 15 — pauses and says, “I knew she was really nice and kind and really supportive.”

It took everything that Sandy had not to tell Andrew that they had started the adoption process. It was even awkward to arrange a chance for Mark, who works for the B.C. Ministry of Citizens’ Services, to meet Andrew. In no way did the Teels want to raise Andrew’s hopes in case the adoption didn’t go through.

When Mark did get a chance to observe — just observe — Andrew, he had an instant affinity for him. “Andrew looks like part of our family,” he told Sandy. “This little boy is part of us.”

Gradually, family services allowed Andrew to visit the family at their home. On the night of his first sleepover, Andrew became very distraught at the thought of having to leave the next morning.

“He was just heartbroken,” Sandy says, “and I thought, ‘Enough trauma.’” She called family services that night to say Andrew was staying. “From that day on it felt as if he has always been here.”

Giving back

Every year until he was 12, the Teels took Andrew on a Christmas adventure. It might be the Stanley Park train or meeting Santa Claus on the top of Grouse Mountain. Doubting he believed in Santa any more, they asked him if he wanted a different Christmas tradition.

He came to them with an idea: he wanted to collect items for a really big stocking to donate to Christmas Inside Out, an initiative for homeless people. He started a simple fundraising drive among his classmates and gathered enough toiletries, small gifts and treats to fill eight stockings.

On a cold and dark Christmas Eve the Teels loaded the stockings into their minivan and went to Oppenheimer Park in the heart of the Downtown Eastside. Twelve-year-old Andrew was moved by the people he met, and the compassion they showed each other.

“It was the best way ever to spend Christmas Eve,” Andrew wrote in a YouTube slideshow.

The next year, Andrew turned to the entire school and together they collected enough items for 30 stockings.

When he called the organizer of Christmas Inside Out, however, he learned that she had health problems and wasn’t able to organize the event. Who would he give the stockings to?

Jennifer Hall, the development officer at Covenant House Vancouver, answered the phone when the Teels called the Drake Street drop-in centre. When Andrew heard that many of the teens it serves had aged out of foster care or run away from abusive homes, he wanted to help.

“It just felt like a perfect fit for them,” Hall says.

As well as donating the stockings, Andrew started a new initiative called Twoonies for Teens, adding an extra $308.

Last year, Andrew took it a step further. He talked to Hall and said, “Maybe Covenant House needs money more than it needs stockings.” He started a fundraising page on Covenant House’s website, including a slideshow that talked about what it was like to be a young person without a home at Christmas.

The media picked up the story and, together with his new schoolmates at Inquiry Hub secondary school in Coquitlam, Andrew’s Twoonies for Kids raised an astounding $49,451.

Andrew has no expectation that he can pull off such a feat again. He’s set a modest goal of $1,000 for this year’s campaign.

On November 16, Jennifer Hall was one of the 900 people who gave Andrew a spontaneous standing ovation when he was presented with an Outstanding Youth Philanthropy award at the Vancouver Convention Centre. On behalf of Covenant House, she had nominated him for the award, presented by the Vancouver chapter of the Association of Fundraising Professionals as part of its Philanthropy Day celebration.

Hall has been deeply impressed by Andrew’s mix of happy-go-luckiness and humble generosity. “Andrew has had some pretty terrible experiences in his young life,” she says. “Sometimes people go dark and he’s got something in him that makes him want to overcome it by doing something positive.”

Andrew knows that if it wasn’t for Sandy, Mark and Darren, he could easily be one of the young people that Covenant House supports. Echoing the words of his mother when he asked why she gave each of the children in her care a hug every morning, he says, “I want them to know people care about them and they’re not alone.”

Covenant House is funded 94 per cent by private contributions. If you would like to support Andrew’s campaign go to CovenantHouseBC.org.