Editor’s note — John Kurucz is of Hungarian descent and related to four of the Sopron alumni

Alongside 30 classmates armed with rifles and anti-tank cannons, Antal Kozak barrelled down a stretch of highway in western Hungary prepared to fight against a combat juggernaut immeasurably more powerful than his own.

The date was Nov. 4, 1956 around 4 p.m.

Kozak was in his early 20s and studying forestry at the University of Sopron, located roughly 15 kilometres from the Austrian border.

His home country was in the midst of a two-week uprising against Soviet rule that was on the precipice of total collapse and defeat. It began on Oct. 23, now recognized as a national holiday in Hungary, when more than 20,000 protesters demanded democratic reform and freedom from Communist rule in the nation’s capital of Budapest.

“It was a very, very difficult time in my life,” Kozak recalled.

The Soviets initially began withdrawing their forces. Performing in front of more than 55 million TV viewers, Elvis Presley later appealed for donations and peace for Hungary on the Ed Sullivan show.

The Soviets returned en masse to crush the uprising on Nov. 4. On that day, Kozak and his classmates moved south towards the Hungarian town of Kophaza to face the oncoming Soviet tanks. They soon realized their weapons had been sabotaged and none would fire.

The Battle of Kophaza would end up being a bloodless fight without a shot fired. Instead of engaging the Soviets in combat, Kozak and more than 200 forestry students and faculty from the Sopron university fled to Austria. The refugees left with less than two hours’ notice and had little time to gather belongings or communicate with family. More than 2,500 died and an estimated 200,000 people fled. About 37,000 refugees ended up in Canada.

Mass exodus

The implications of those events will be felt on Canadian soil for centuries, and difficult to quantify financially, culturally or from an environmental perspective.

“We could see [the Soviets] coming and we tried to stop them, but of course we couldn’t,” said Kozak, now 80 and living on Vancouver’s West Side. “I turned around and I started running one way, the other guys started running in other directions. I didn’t even have time to go get any of my things. I had one pair of pants and a sweater. It was time to go.”

The Hungarians lay in wait for weeks in Austria, hoping for some form of Western intervention.

None came.

“It was a total panic,” said Laszlo Pinter, a 79-year-old Parksville resident and former Sopron student. “Everybody expected [the Soviets] to do something terrible, so we had to run.”

In late November 1956, the forestry group sent correspondence to more than 20 countries asking for help. Specifically, they were looking for a country with an established forestry school so their studies could continue.

Canada answered their call within weeks. Then Immigration Minster Jack Pickersgill worked alongside officials from the University of British Columbia, which opened its forestry school in 1951, to arrange for the mass exodus.

The Hungarians began arriving in New Brunswick in January 1957. By September of that year, they began their studies at UBC. It was an around-the-clock exercise in learning English, transitioning into a new society and honing their studies as professional foresters.

A former dean of the forestry program, Bob Kennedy is the lone surviving UBC forestry faculty member from the time the Hungarians arrived.

“Our faculty would meet with the Hungarians, and I remember when they first arrived someone said to them, ‘It’s a nice day isn’t it,’ and they would respond with, ‘Yes, we like apples too,’” he recalled with a laugh. “Even though they couldn’t speak English at first, it was evident they were very serious about their studies.”

Hungarian influence

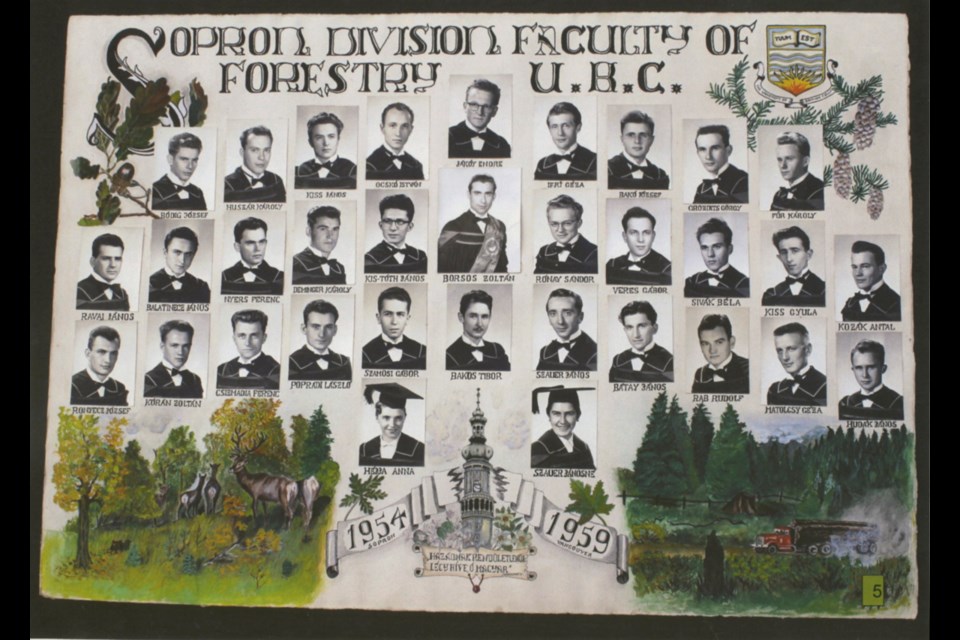

The Sopron foresters graduated from UBC in four waves between 1958 and 1961. One third of the 140-plus grads obtained post-graduate degrees, and worked as professional foresters, engineers, biologists, in academia and all levels of government. Kozak became a UBC professor and later an associate dean of the forestry faculty. His son Robert now serves as an associate dean of the forestry faculty as well. Pinter worked for more than 30 years for MacMillan Bloedel, now known as Island Timber, on Vancouver Island.

At the time of their graduation, skilled foresters were in short supply in Canada. The Hungarians helped revolutionize forestry concepts — specifically the practice known as sustainable yield — in B.C. and Canada because those methods had been employed in Europe for centuries.

Sustainable yield uses a series of metrics and indicators that gauge how long a forest takes to renew itself and the necessary steps to sustain a steady tree harvest in perpetuity.

The practice involves distributing specific tree species, in specific areas, in specific intervals to ensure a constant state of growth and vitality.

“This was all pretty new to us, but it was not new to the Sopron foresters,” said Peter Pearse, a professor emeritus of economics and forestry at UBC. “These Hungarians were comfortable with this and our foresters here were struggling with it. They were very enthusiastic, they were very well educated and they were determined to do a good job.”

While the Hungarians were responsible for the health of millions of trees across Canada, quantifying their financial contribution is impossible.

G.C. Andrew, deputy president of UBC in 1957, wrote in the early 1980s, "I have always looked at their arrival in Canada, and particularly in B.C., as one of the most profitable immigration dividends the country has had."

Jack Saddler has worked at UBC since the early ’90s, and served as forestry faculty dean from 2000 to 2010. He said money is not the metric to characterize the Hungarian contributions.

“Up until they came in, we looked at forests like the cod — we thought it would last forever,” he said. “We thought we could go in without a calculated plan, that everything would regenerate because the forest was just so enormous. They realized if they want their great grandchildren to enjoy the forest, that it had to be managed in a sustainable fashion.”

The Hungarian influence was formally acknowledged by the provincial government last month. The week of Oct. 23 to 29 was declared Hungarian Cultural Week in B.C. to recognize “the role and contributions Hungarian refugees have made economically, socially and culturally to the province.”

During that week Sopron grad and former Vancouver resident Les Jozsa was posthumously given a lifetime achievement award from the Hungarian government for his work in forestry, art and promoting Hungarian culture. It’s the highest civilian honour awarded to Hungarian nationals.

Reflecting on his 60 years in Canada, Kozak has nothing but gratitude for his adopted country.

“Everybody is free. You can get jobs. You can buy any type of food, you can buy a car — I could go on forever,” he said. “If you work hard in Canada, very likely everything in your life will be beautiful.”