Don’t be deceived by Esther Matsubuchi’s gentle spirit. She has a core of pure strength.

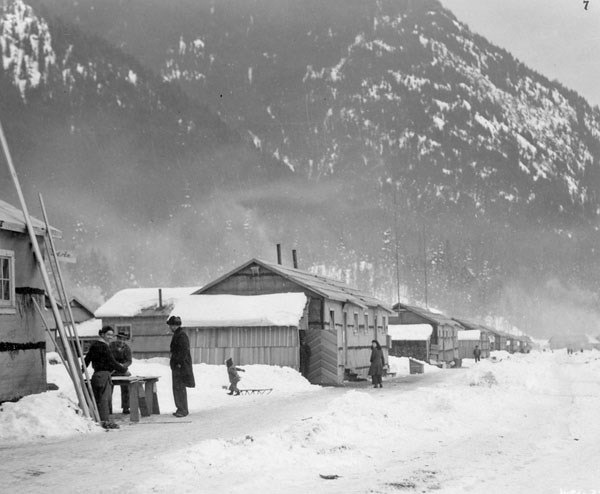

Born in Vancouver, she was five years old when her family was forced out of their home and moved to a Japanese internment camp in the West Kootenays in 1942. With nothing to their name after the Second World War ended, they moved to Ontario’s farm country, working long days for little money.

She was pregnant with her second daughter when a car accident crushed her skull, lacerated a leg and shattered a femur. She spent the last two months of her pregnancy in the hospital.

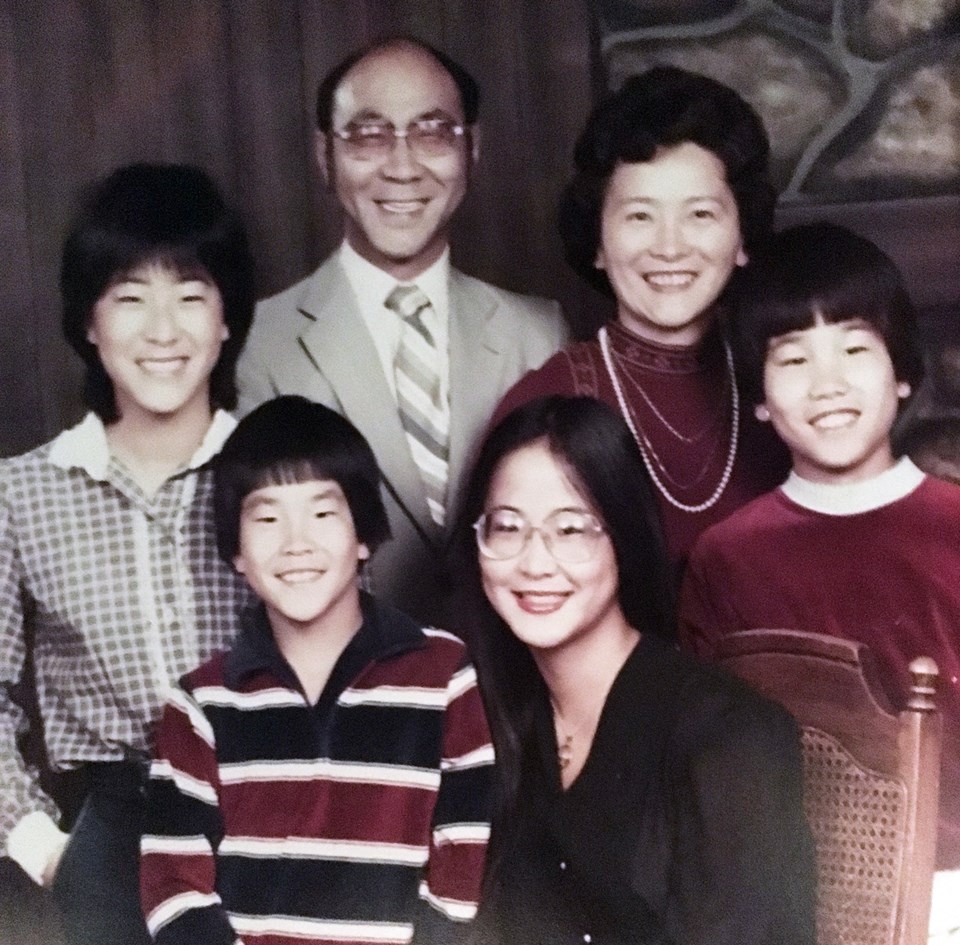

She gladly followed her husband’s career in civil engineering around the world, enjoying the adventure of raising four children in places such as Algeria, England and Haida Gwaii.

Diabetic, she’s survived cancer twice. She cared for her late husband Ed during his 15 years of illness, including bladder cancer.

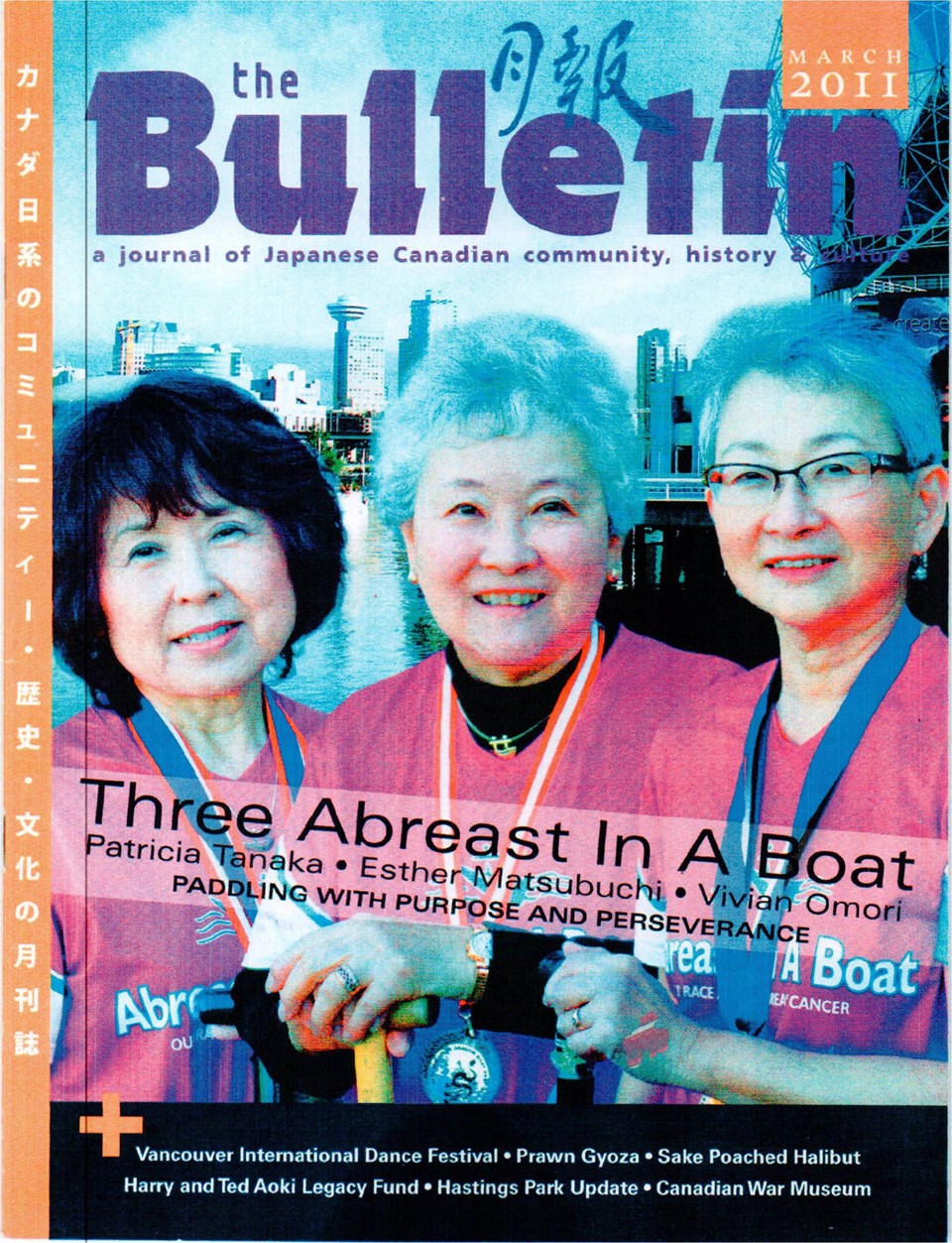

A pioneer in the breast cancer dragon boat community, she was part of a study that proved women would benefit from upper arm exercise after their treatments. Until then, women were told not to move their arms in a repetitive manner, not even to knit.

And when a North Shore Anglican church planted a cutting from a Kogawa House cherry tree, Matsubuchi successfully lobbied to have the church cut it down. The tree was from the Vancouver home where Anglican priest Gordon Nakayama first raised his family, including his daughter Joy Kogawa, who chronicled life in the internment camp in her novel Obasan. The priest had sexually abused four of Matsubuchi’s five brothers, among others, desecrating the family’s trust when he crawled into the boys’ beds when he came to visit.

On May 16, Matsubuchi will receive Coast Mental Health’s Courage To Come Back award in the social adversity category. Her resilience in the face of so many hardships will be applauded and honoured by the 1,500 people gathered at the Vancouver Convention Centre.

Matsubuchi’s mother was 16 when she moved to Vancouver in 1922. Her father had been a wanderer, travelling to Cuba, South America, Mexico and San Francisco before a visit to Vancouver convinced him to marry and settle down. The Matsubuchis had three sons before Esther was born, followed by two more sons.

Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbour in December 1941 triggered a not-so-latent fear and suspicion of Japanese-Canadians, even though the majority of the 21,000 residents had been born here. There were already laws in B.C. that prevented them from getting certain jobs and voting. With the press stoking further distrust, the Canadian government forced them into internment camps. Allowed to take few possessions with them, whatever was left behind was eventually sold by the government to, it said, pay the costs of the camps.

“Those people who confiscated everything, they were like [U.S. President Donald] Trump,” Matsubuchi says. “It would never happen again.”

Vancouver had two Japanese Canadian Anglican churches before the war and, as part of that community, the Matsubuchis were sent to the Slocan City camp north of Nelson after first being detained in the stables at Hasting Park.

Once they were at the camp, where David Suzuki also lived, they were told to speak only English; as a result, Matsubuchi speaks Japanese with a five-year-old’s vocabulary. Conditions were poor but there was no mistreatment, Matsubuchi says.

Her father worked as a gardener, growing the vegetables for the camp’s hospital. “My parents just said, ‘God will carry us through.’ They were very faithful.”

After the war, the family was sent to work at the farm of a well-known Anglican in Cedar Springs, near Chatham, Ontario. When her brothers tried to augment the family’s income by mowing lawns on top of their summer jobs on the farm, they were told to stop. “The farmer would say, ‘You can’t do that because you’re living in my house on my land.” One of her brothers was offered a hockey scholarship “but we were so poor we couldn’t give him the spending money.”

As a roving priest in communities where Japanase-Canadians gathered, Gordon Nakayama ministered there.

In 1994, Nakayama confessed to the church that, "I made mistake. My moral life with my sexual bad behaviour. I sincerely sorry what I did to so many people.” Instead of making the confession public or telling the police, the church fired Nakayama for immorality and allowed him to quietly retire.

“My brothers tried to bring it up and my parents scolded them for talking like that. They just couldn’t believe a man of his teachings and profession would do things like that,” Matsubuchi says. Later, when a church meeting was held about Nakayama’s crimes, the congregation, including her parents, “decided never to bring it up again because it was shameful.”

Matsubuchi refused to be silenced. She was a voice for her brothers, who were deeply emotionally scarred by the abuse, when the tree from Kogawa House was planted and was present when the church apologized to families in 2015.

“It was a tree from an evil man’s house,” she says of why she forced the church to remove it. “I forgive but I do not forget.”

In 1989, Matsubuchi was in Toronto visiting one of her brothers when she felt a pain near her armpit. A doctor misread the test results and gave her antibiotics. Six months later, and back in North Vancouver, the pain hadn’t gone away so she underwent new tests that revealed she had breast cancer and that it had spread to her lymph nodes. She had a lumpectomy and nine months of chemo at Lions Gate Hospital. Her main fear was getting lymphedema, a swelling in arm that can occur after getting lymph nodes removed, so she followed the advice of the day not to move her arms in any repetitive motion such as knitting or gardening.

In 1996, she was at a Bosom Buddies meeting when they were told about Dr. Don McKenzie’s study. A UBC professor, he believed that exercise would actually help prevent lymphedema and was encouraging breast cancer survivors to form a dragon boat team, which the women later called Abreast in a Boat.

“I knew dragon boating was hard and cold so I didn’t think I would join but the women next to me, who were in worse shape, put up their hands so I put up my hand.”

She’s been paddling ever since. As Dr. McKenzie noted in his report summary a couple of years later, the approach “reaches out to other women and offers them a message of hope and support. It is helping to change attitudes toward ‘life after breast cancer,’ and it encourages women to lead full and active lives. It is making a difference.”

Today there are more than 200 teams around the world. Racing became part of her and her husband’s vacation schedule, taking them to such places as New Zealand, Malaysia, Poland and Seattle.

Widowed since April 2106, Matsubuchi is still very much involved in a variety of fundraising efforts for the Canadian Cancer Society. She had a hysterectomy and radiation five years ago after being diagnosed with endometrial cancer and Ed had survived bladder cancer before succumbing to complications arising from his diabetes.

“I take one day at a time,” she says. “I’ve lived my life and don’t have to worry much. It’s only the ‘big thing’ coming up.

“Any time anything good happens, I think of the Johnny Appleseed poem: Oh, the Lord's been good to me.And so I thank the Lord, For giving me the things I need: the sun, the rain and the apple seed; Oh, the Lord's been good to me.”

The Courage To Come Back Awards, presented by Silver Wheaton, are May 16. The gala is a major fundraiser for Coast Mental Health.