Christmas Eve, 1956.

In the dead of a winter night, with snow thick on the ground, Hungarian refugees slip across the Austrian border, fleeing the Soviet crackdown on a failed uprising.

Some 751 refugees cross the border that night alone, as does a Russian tank soldier — likely one of those whose tanks smashed Budapest on Nov. 4 — who stepped off a freight train, handed his pistol to border police and asked for asylum.

Among those fleeing Hungary that night were four people with a local connection: they were led by a human smuggler who’d been hired by a Vancouver family to get them out.

The Vancouver Sun told the tale in a Dec. 27 front-page story headlined “Sun Reporter Helps Four to Escape Reds.”

Jack Brooks, staff reporter, was in Vienna covering one of the biggest stories of the year: the exodus of 200,000 Hungarian refugees into neighbouring Austria and the “freedom flights” that would ultimately bring 37,000 of them to Canada. In early December, Vancouver resident Ty Wamosher contacted Brooks, asking if he’d broker the escape of his wife’s mother, brother, sister-in-law, and their child.

“They had read my story... describing how guides could be sent in to bring others out,” Brooks wrote. “They phoned the Sun and said they were ready to pay if it could be arranged.”

Brooks met the smugglers at a cafe near St. Stephan’s Cathedral in Vienna. The fee was $500 per head — equivalent to more than a month’s wages — or $125 per head if those in Hungary were contacted but didn’t want to go. The Wamoshers cabled the money to Vienna.

Brooks described the deal: “With a two-inch-thick wad of dollars in my pocket I went to a hotel down one of Vienna’s dingy, narrow streets. The contact counted the money carefully. The man who would go over the bloody borders watched closely and flashed his silver teeth in agreement.”

Passwords were chosen by the Wamoshers — phrases that only they would know, to prove that the man knocking at the door of their relatives wasn’t a Soviet agent: “Dudus says Lili’s ring is still in Switzerland” and “Cula remembers how you and Nyuszi were still seasick in the car travelling from London to Folkestone.”

The money was placed in trust with a local rabbi, who would hold it until the smuggler returned either with the relatives — or with a letter, saying they didn’t want to leave Hungary.

Then the smuggler crossed the border. Hours later, there came startling news: three of those he’d gone to retrieve had already crossed the border. Only Mrs. Wamosher’s 67-year-old mother was still in Hungary.

Two days of tense negotiations followed: those in Vancouver wanted three different people brought out.

Eventually, a deal was struck, and the smuggler returned with four people, arriving in Austria around 1 a.m. on Christmas Day.

“Communist guards held them several hours,” Brooks wrote. “There was fear of prison, of deportation, even execution. But eventually they were allowed to go. The second guide picked them up and led them on a 30-mile foot slog through frozen fields and marshes to the border.”

New home for Christmas

Meanwhile in Vancouver, the Vancouver Sun reported that 250 Hungarian refugees who’d already come to B.C. had each been placed with a local family for Christmas.

“And that means they will be warm, well fed and as merry as they can be in a strange new home,” the newspaper said. “With the people of B.C. opening their doors and hearts the big influx is proving less of a problem than anyone anticipated.”

Alex Lockwood of the Department of Immigration estimated that about half of the male Hungarians in Greater Vancouver had found jobs; many were already working in grain elevators and other labouring jobs.

“The big barrier for all but a handful of the Hungarians is the lack of English,” the paper reported. “A few speak English, or took it in school and have re-mastered it quickly but more than 20 did not know even the basic 'Yes' and 'No' when they stepped off the planes.”

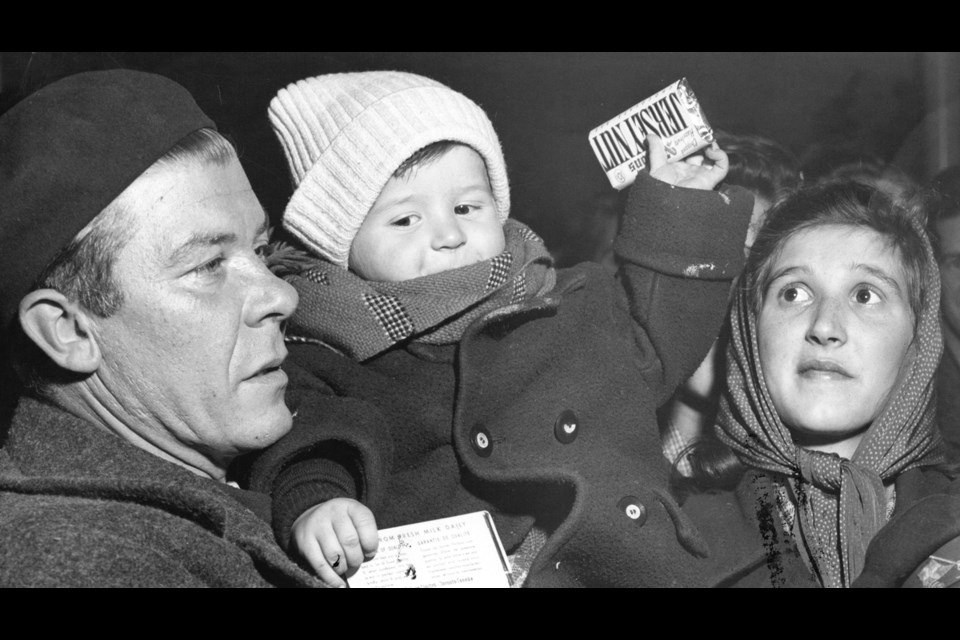

The “freedom flights” brought refugees to Vancouver’s airport on Sea Island. A Province newspaper photographer captured images of several of them arriving on Dec. 6: families and single people, most of them young.

On Christmas Eve, the Province reported: “The plight of Hungarian men, women and children fleeing from their homeland after Russian forces crushed their bid for freedom has caught the imaginations of Canadians. There were some protests but these have not dimmed the desire of other Canadians to open their hearts to the refugees.

“Officials of the federal immigration department say they have never seen Canadians rally to a cause so readily and with such affection… Refugees now are arriving in Canada almost daily by ship and plane. The total will be 4,429 by Christmas Day.”

The paper commented on the quality of the refugees: “A large proportion are professional, skilled or semi-skilled people. They are expected to make a major contribution to Canada’s productivity.”

The federal government, the paper added, had thus far committed itself to bring about 20,000 Hungarians to Canada. “Some 7,500 will have landed or be on their way by the end of the month and about 10,000 are expected by the end of January.”

Another story in the same newspaper reported on the arrival of Elizabeth Markstein, her son Vendel and his wife Maria, who’d fled their village of Varoslod following the uprising and had since joined Elizabeth’s husband Tony near Nanaimo. The paper described their two-day, 125-mile overland trek away from the “Red terror.”

“Sometimes they went by rail but as they approached the larger towns, which were ringed by Russian tanks, artillery and troops they walked by night to evade patrols. They had no food — only a bottle of rum.

“Several refugees were caught but the Marksteins made it successfully to the border. There they spent three bitter hours crawling on their stomachs across frozen ground to the border into Austria. Several times they were machine-gunned and many others were shot or wounded.

“They crossed the Einser Canal at the border three days before the Russians blew up the bridge.”

Some Canadians flew to Austria to join the international relief effort. These included Sybil Conery, executive secretary-treasurer of Save the Children Fund’s B.C. branch.

Conery told the Province that Hungarian parents gave their children sleeping tablets so the children would be quiet during the border crossing. Some parents gave their children too much, and the overdosed children nearly didn’t wake up.

“It kept them quiet all right, but when they reached the border camp we daren’t have let them sleep or they would have died,” Conery said. “So we stayed up with them, all night, clapping hands, throwing ball and talking to them... Some of the children came across with their arms frozen stiff and their clothing had to be either cut off or thawed out.”

Conery added: “Austria is such a poor country itself that it cannot possibly support all the refugees pouring in and I think we ought to do something.”

Welcome to Vancouver

On Christmas Eve, the Sun ran a photo of Tamas Neszmelyi and his wife, together with their nine-year-old son Tomi, praying in front of a cross at Calvin Hungarian Presbyterian Church at Main Street and 24th Avenue.

“Giving Humble Thanks at Christmas is new Canadian family which only two months ago lived under Russian domination in embattled Hungary,” the photo caption read.

Immigrant communities within Vancouver rallied to help the newcomers. The Sun reported that German Canadians provided Christmas presents for the Hungarian refugees in response to a Dec. 13 article in Der Courier, a German-language weekly newspaper, which appealed to “the many of you who have known what it is to be a refugee.”

More than 300 “gaily wrapped” parcels poured in from all over B.C. as a result. Hungarian refugees continued to arrive in Vancouver in the days following Christmas.

On Dec. 27, the Sun reported the arrival of another 66 Hungarians at the airport, including 13 children. The refugees had fled in late November, and spent a month at a refugee camp in Austria.

P.W. Bird, a settlement officer, told the newspaper, “This is the best group we’ve had. They are mainly professionals and skilled tradesmen. They’ll all be settled by Friday.”

Bird contrasted the recent arrivals with the first refugees to come to Canada.

“The first groups we had were poorly dressed, had nothing. These are less bewildered, are warmly dressed and have extra clothing.”

The Hungarians received a meal of ham and eggs, toast and coffee. The children all received belated Christmas presents.

The group included “Charles” and “Susanne,” a radiologist and an X-ray technician who soon planned to get married.

The newspaper quoted him as saying: “We escaped together. There was no attempt to stop us... This is the best Christmas we’ve ever had.”