Vancouver's homeless population is now the highest it has ever been since data was first collected in 2005 to determine how many people are living on the streets and in some form of shelter.

Statistics released Tuesday by the city's director of homelessness services, Ethel Whitty, to city council showed 2,181 people were counted by more than 400 volunteers over two days in March.

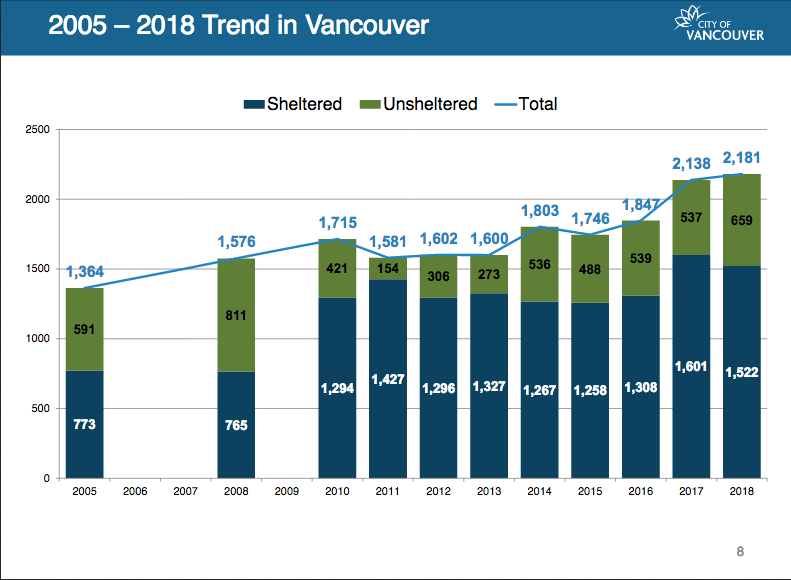

That's 43 more people than were counted in 2017, which at the time was a record-breaking total. In 2005, a total of 1,364 homeless people were counted across the city.

"Homelessness in Metro Vancouver and across the province is a humanitarian crisis that reflects a trend seen across the country and the continent," said Whitty, noting 11,643 homeless people were recorded in Seattle's 2017 homeless count.

Whitty cited low vacancy rates, the loss of single-room-occupancy hotel units, high rents at some of the hotels, overall rising rental rates, chronic poverty and the "stigma" related to being homeless as drivers of homelessness.

Over the years, the number of people living on Vancouver streets has fluctuated dramatically, with 591 recorded in 2005, then dropping to an all-time low of 154 in 2011 before increasing to 659 this March.

The population in shelters has seen equally dramatic shifts, with a low of 765 people recorded in 2008. That jumped to an all-time high of 1,601 last year, although Whitty noted additional extreme weather shelters were opened during last year's count; this year's total of people living in shelters was 1,522.

The increase in homelessness this year comes despite the city finding 850 homes for residents who were homeless, or at risk of homelessness in 2017.

Since last year's count, about 435 new social and supportive homes—these are homes where tenants have access to health care experts and counsellors—have opened. About 190 were rented at the $375 per month welfare shelter rate.

The city also expects more than 600 permanent subsidized homes and all 600 planned temporary modular homes to open by the end of the year. So far, 156 units in modular homes have opened at sites in Marpole and in the Downtown Eastside.

The findings from the count revealed much of what previous counts have shown—that the majority of homeless are men between 25 and 54, with many living with a medical condition or illness (44 per cent), mental health issue (43 per cent), a physical disability (38 per cent), or a combination.

That information was collected from 659 people living on the street and 791 in shelters. For the first time in conducting the counts, volunteers asked people whether they had an addiction, with 35 per cent saying they didn't have one.

Whitty said questions about addiction were to provide facts on the profile of a homeless person, despite sweeping assumptions and generalizations of people without a home.

She referred to the debate that erupted with some Marpole residents opposed to the temporary modular housing complex in Marpole.

"For instance, we find some hold a belief that all homeless people are injection drug users," she said, before providing self-reported data that showed otherwise.

Those with addictions cited cigarettes (28 per cent), followed by opioids (25 per cent), methamphetamines (23 per cent) and alcohol (22 per cent) as main substances. Marijuana was at 20 per cent and cocaine at 12 per cent.

The data also revealed 523 people had multiple income sources, including income assistance (38 per cent), disability benefits (29 per cent), full or part-time employment (19 per cent) and binning (10 per cent) but still couldn't afford rent.

More than 50 per cent of the homeless told volunteers they had been homeless a year or less, with 31 per cent less than six months and 21 between six months and a year.

Of those surveyed, 78 per cent said they last paid rent in Vancouver prior to becoming homeless, dispelling a long-held myth that the city's population is being fueled by migration from other cities and provinces.

"People don't get on a bus with a big shopping cart and come here," Whitty said in response to a question from NPA Coun. Melissa De Genova about where people are originally from before becoming homeless in Vancouver.

Indigenous people continue to be vastly overrepresented in the city's count, representing 40 per cent of the homeless population despite making up 2.2 per cent of Vancouver's overall population.

"We see that about 52 per cent of the Indigenous homelessness population is actually unsheltered, and that's significant for a range of reasons," said David Wells, chairperson of the Aboriginal Homelessness steering committee, who told council services and options for Indigenous people are not connecting to people on the street.

"It's endemic of the massive intergenerational traumas that have been experienced, the colonial history, things of that nature—we're not seeing that connection to the services that are there."

@Howellings