By now, you’ve likely heard the news that the Squamish Nation is proposing to build a large-scale housing development on its land under and around the south end of the Burrard Bridge.

But have you heard what Mayor Kennedy Stewart has said about the proposal for the 11.7-acre site?

“This is what reconciliation looks like,” the mayor tweeted over the weekend.

Is it really?

I pose the question not to doubt the mayor’s sincerity and his commitment to work “government to government” with First Nations, but in seeking clarity on what he’s actually saying about this project.

Reconciliation is a big, important word for Indigenous peoples, as it is for some governments, including the City of Vancouver and its previous and current city councils.

In recent years, progress has been made at city hall in the name of reconciliation, including proclaiming Vancouver a city of reconciliation and endorsing the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

All council meetings begin with the mayor or the chairperson of a committee recognizing Vancouver is on the unceded traditional homelands of the Musqueam, Tseil-Waututh and Squamish.

Over the years, there’s been ceremony, the installation of art in the council chambers, training for staff on First Nations history and funding for Indigenous programs.

The city also has a manager of Indigenous relations and last year turned over a piece of land on Milton Street, with an estimated market value of $2.3 million, to the Musqueam as part of its commitment to reconciliation.

That’s quite a lot.

But Squamish Nation leaders will point out that reacquiring a chunk of its land under the Burrard Bridge had nothing to do with reconciliation or the good work at city hall.

It had everything to do with winning court battles.

The land was once home to an ancestral village known as Senakw until the government of the day forcibly removed Squamish members in 1913 and burned the village to the ground.

It wasn’t until 2003 that the Squamish reclaimed the land after decades of court battles, which involved the Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh, which challenged ownership of the property.

At the time, the property was in the hands of Canadian Pacific Railway until the B.C. Court of Appeal returned it to the Squamish.

So is that reconciliation, or recognizing rights and title to land?

I spoke to Ian Campbell, a Squamish hereditary chief, back in 2016 about this piece of history. We sat on a bench on the edge of the property near the Coast Guard station.

“It cost millions of dollars [in legal costs], it had taken decades to achieve and unfortunately it was very divisive amongst the three nations,” Campbell said.

During that conversation, Campbell said the Squamish originally proposed building two towers—possibly rental—on the west side of the bridge. Profits from that first phase would be used to build a mixed-use development on the east side of the bridge.

The plans now, as heard from Squamish councillor Khelsilem, could see up to 3,000 housing units, possibly all rental, built on the property. The nation’s members still have to vote on it and choose a developer.

The City of Vancouver, meanwhile, has no say in what is built.

The city would be responsible for supplying roads, fire and police services. Water and sewer systems would come via the Metro Vancouver agency.

So what does Khelsilem think—is the development of this property what “reconciliation looks like?”

“It’s a good question,” he said by telephone Monday. “I think there are parts of it that are connected to a conversation around reconciliation and they’re parts of it that aren’t.”

Added Khelsilem: “The Squamish Nation choosing to develop our reserve land and go through that process of using it for economic development, I don’t know if that necessarily is the definition of reconciliation.”

But, he continued, the broader conversation with the City of Vancouver, which has recognized the Squamish and other nations as another level of government, is central to reconciliation.

He suggested the topic of land use and how the city may want to run a streetcar line through the property is better discussed collaboratively than each government working against each other.

“Working with them will probably improve the project, but it will also hopefully improve the city,” Khelsilem said.

I learned Tuesday the Squamish and Vancouver councils met Monday night for three hours at the Vancouver Museum as part of the city’s commitment to meet with the three local nations.

The mayor broke the news of the meeting during his regular media availability sessions at city hall. He described the meeting as “very warm and congenial, hugs all around.”

Stewart said the city is working on a renewed memorandum of understanding with Squamish. He talked about recognizing the past and moving forward in the name of reconciliation.

That said, he didn’t directly answer my question on how the project under the Burrard Bridge is what “reconciliation looks like.” Or maybe he did.

You tell me:

“The larger phrase is truth and reconciliation, and so truth is acknowledging the past at that site, where in 1913 the original Squamish inhabitants of that settlement were forcibly evicted off the land and their houses were burned to the ground. I think it’s important for us as a city to recognize the relationships then were horrible, and I think the ongoing legal disputes and fights all the way through to get to where we are today…”

I’ll stop there because he never does answer my question.

In pursuing an answer prior to the news conference, I received an email from a member of his staff that referred to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s definition of “reconciliation.”

It goes like this:

“Reconciliation is about establishing and maintaining a mutually respectful relationship between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples in this country. In order for that to happen, there has to be awareness of the past, and acknowledgement of the harm that has been inflicted, atonement for the causes, and action to change behaviour.”

Again, how does this fit into a First Nation fighting alone for decades to reclaim what was theirs and is now embarking on an economic development opportunity to boost up its people—all of it done without any help from the City of Vancouver?

At this point, it’s a rhetorical question.

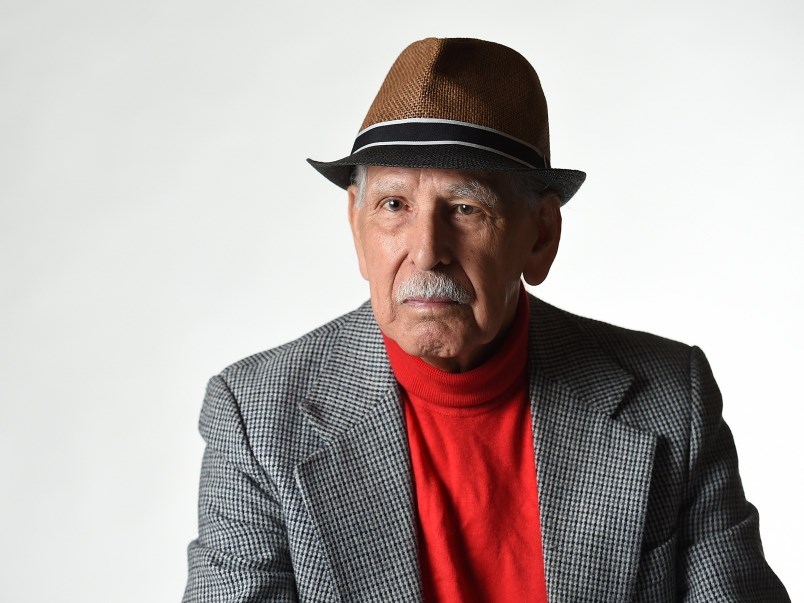

I thought of the late Indigenous leader, Bill Lightbown, when I started writing this piece. He died last month at 91. Three years ago I spoke to him about the struggles of Indigenous peoples over the decades.

Was life getting better?

Yes, he said.

“And the reason it’s better is because of the long struggle that went on with our people and governments,” he continued.

That struggle, as Lightbown saw it, is rooted in the oppressive laws of government that set up reserves, seized land, forbade Aboriginal ceremony, excluded Indigenous people from voting and rounded up children and took them to residential schools.

It had only been through successful court battles, he said, that progress had been made on these fronts. He referred to some of the landmark cases, including Delgamuukw, Calder, Guerin, Sparrow and Tsilhqot’in decisions, as well as the long-running Ontario lands claim case known as Bear Island.

It has not, he added, been simply a sudden act of goodwill from governments that led to some relief in Aboriginal communities, including First Nations reacquiring land.

“The government and entities are scared stiff that we’re going to use their own laws against them,” he said. “That’s the reason they’re starting to cooperate with us. For years and years, they didn’t recognize us as people. We are the original people from this land and we deserve the recognition and respect that goes with that.”

@Howellings