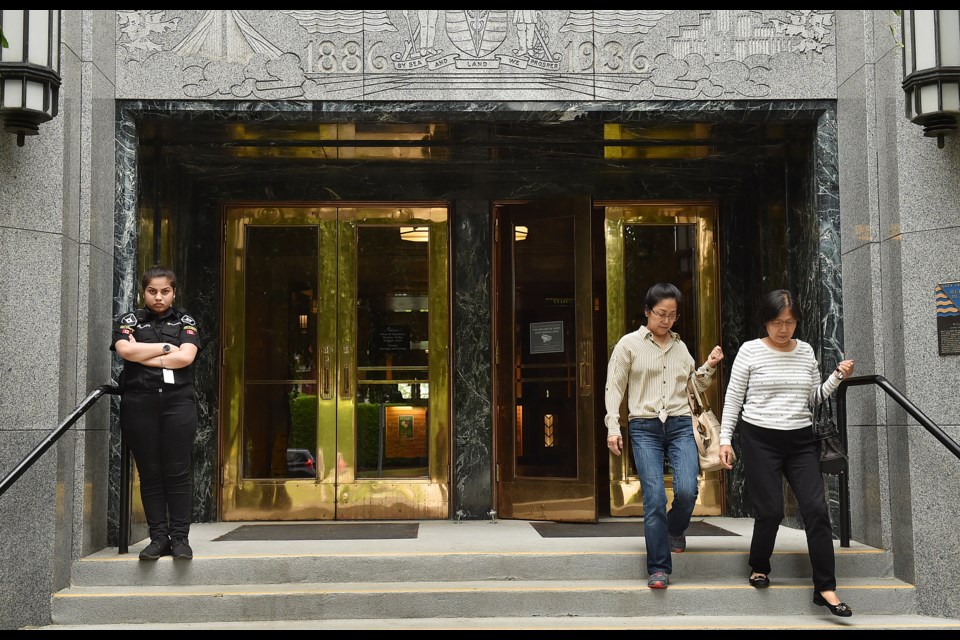

I've been meaning to write something about the increase in security guards at city hall on council days.

If you’ve been there in the last while, the guards’ presence is very noticeable, as it was at Tuesday’s public meeting.

First, some historical perspective…

In my experience, it’s not unusual to have a guard in the information kiosk on the main floor of city hall. It’s also not unusual to have one or two in the foyer outside the council chamber, which is on the third floor.

But that’s about it.

During my visit Tuesday, there were guards posted at both main entrances to city hall — two at the front doors, one at the back doors.

Inside, there was a guard at the kiosk.

I usually take the stairs up to the third floor, but I’ve learned not to because the door at the top of the stairs is now locked for security reasons.

So I take the elevator.

When I get off the elevator, there is a security guard there, who is monitoring arrivals like me. Depending on your business, you may or may not proceed through another locked door into the third floor foyer.

That’s where you’ll find another guard standing at a lectern outside the council chamber. That’s a total of six guards in uniform. Four of them were from Securiguard, two others were city employees.

There may have been others in plainclothes, but I can’t be certain.

Makeshift coffin

So what do you think — is this an appropriate number of guards at a public building at a time when the world is a much different place than it was before 9/11?

Or is it excessive in a city where people generally get along and should have access to a building where harm reduction activists once carried a makeshift coffin into the council chamber back in September 2000?

I posed those questions to councillors Adriane Carr, Melissa De Genova and Jean Swanson. I also spoke to longtime harm reduction activist Dean Wilson about the coffin.

Charles Gauthier, the president and CEO of the Downtown Vancouver Business Improvement Association, has been a regular visitor to council over the years, so I spoke to him, too.

Finally, I made some Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act requests (which didn’t reveal much) and received some emailed answers from Greg Conlan, the associate director of the city's protective services, to some questions (which said a bit more).

The budget for security personnel at city hall is just under $700,000 and increased slightly for 2018 — by less than $70,000 — “due to enhanced safety and security practices on council days,” Conlan said in the email.

So to the obvious question: Why an increase in security guards on council days, and what is the rationale for it?

“Prior to the new procedures put in place, there had been increased acts of aggression and disruption which created anxiety for councillors, city staff and the public, and also interfered with the democratic process,” Conlan said.

“Since the new procedures have been implemented, there have been no significant incidents of concern.”

The city didn’t elaborate on the “acts of aggression and disruption,” but I am aware of an individual who has acted aggressively at city hall long before the increase in security.

Former councillors are aware of this, so is security.

So why the increase now?

Swanson believes the measures may be connected to her visit to city hall back in June 2017.

That’s when Swanson, who wasn’t a councillor at the time, and housing activists stormed the council chamber. They held signs that said, “Our homes can’t wait” and chanted the same message.

The mayor and councillors left the chamber, and Swanson ended up in the mayor’s chair. She led a mock council meeting before all involved left the chamber. No one got hurt.

It was shortly after Swanson’s time in the mayor’s chair that more security guards were put in place at city hall. Also, the city now only allows a small number of speakers in the chamber and created an overflow area on the main floor.

“That’s when it started,” said Swanson, who was elected in October 2018.

So what does she think now that she has an official seat in the chamber?

“It’s making it seem like the city is not open to everybody, especially because it’s usually Downtown Eastside residents who get the brunt of the security,” she said, noting she receives texts while sitting in council from people who say they can’t get past security.

“I know these people. They’re not going to hurt anyone. I think it’s a little bit harsh.”

Added Swanson: “I think [security] might get the odd threat against people, and if they know something that I don’t know, then I guess it’s legit. But when there are no threats and when it’s just citizens — maybe they’re vociferous citizens — coming to city hall, I think they should be welcomed.”

Carr was at the meeting in June when Swanson and others stormed the chamber. Carr said she didn’t feel threatened at that meeting, although she said the act of civil disobedience “went over the line.”

In her three terms as a councillor, despite some of the spirited language from speakers and protests, Carr said she has had no reason to be concerned about her safety.

“From my point of view, it’s excessive,” she said of the security presence.

That said, she added, people throwing stuff from the balcony — as occurred in February — shouldn’t be tolerated. She also has zero tolerance for speakers who disparage city staff.

Carr said she was fine with a smaller complement of security, but recognized other councillors and staff may feel differently than her on the issue of safety.

De Genova had a different take, saying she believes the level of security is appropriate and she trusts city staff’s move to go in this direction.

“Certainly — at least last term — other council members, including myself, did experience some security challenges and difficulties, and that’s all I say,” she said.

In a tweet in March, De Genova said that she was “tossed out of my council chair by protesters” in 2017. She was pregnant at the time.

De Genova pointed out city hall was shut down by housing activists in May 2018. Council was forced to hold a brief meeting in the community garden at city hall.

That protest also involved Swanson’s friends with the Our Homes Can’t Wait Coalition.

Then-mayor Gregor Robertson and some of the councillors were followed by activists as they left the garden. They followed them down Cambie Street to a city building on Broadway.

Most of council got into the building, but activists blocked the doors to keep Carr and then-councillor Hector Bremner outside.

Activists then walked back up Cambie Street to another city building at 10th and Cambie that serves as a centre for people to obtain permits and licences.

The activists circulated throughout the centre, disrupting meetings between customers and staff, with one protester climbing on top of a desk to demand social housing.

Security cleared the building of staff and customers, which prompted activists to leave. At one point, more than 20 police officers were at the scene at city hall, but no arrests were made.

De Genova said she’s heard from people who don’t have a problem with the increased security, and others who do.

“At this current time, I am comfortable with it,” De Genova said. “I understand that it may change and there may be more or less security, depending on the assessments [the corporate security team] make.”

Gauthier said he noticed the increase in security and wondered if it was necessary. But, he added, the recent incidents involving protesters is evidence the security presence is warranted.

“All you need is one incident that’s really severe,” he said, adding that such an incident would then have citizens cast blame on city staff for not being prepared.

“I’m not overly bothered by [the increase in security]. It’s a bit of a minor inconvenience for those of us who go there and abide by the rules. They must have their reasons for doing it.”

Gauthier pointed out that when he visits the B.C. Legislature that it’s like going through security at an airport.

“I just think it’s probably the day and age we live in,” he continued. “If it was lax, maybe there would be some kind of wingnut that would go there and do something really drastic. I think having a presence is a deterrent in itself.”

As a frequent speaker, he said, he’s been heckled and had to turn around and tell the person or people to respect his time at the lectern. The politician chairing the meeting often steps in, too, he said.

“Maybe the people who would rather not have security there are probably the ones that are up to doing some kind of performance theatre in council and getting the media attention,” Gauthier said.

Back in September 2000, that’s what happened when Wilson and members of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users brought a makeshift coffin into the council chamber.

I’ve seen a photo and it’s quite something. Check it out here. (Full credit to Elaine Briere and Travis Lupick)

Wilson and the others were there to protest a decision from then-mayor Philip Owen and his council’s decision to place a 90-day moratorium on spending and services for drug users in the Downtown Eastside.

“I said, ‘Look it — all I want is five minutes. I’ll speak for five minutes and then I’ll leave,’” Wilson recalled. “And I did exactly what I said. I spoke for five minutes and then grabbed everybody and I said, ‘Let’s go.’ We made a deal, and from then on Philip said he knew he could trust me.”

Added Wilson: “Because of how open it was, we were actually respectful of that. If they had pushed back any harder, we would have just gone f***ing crazy.”

Wilson and Owen became allies in the fight for harm reduction services in Vancouver, which eventually led to the opening of the Insite drug injection site in 2003 on East Hastings.

Told about the level of security now at city hall, Wilson said:

“That’s crazy. We used to just walk in, man.”

@Howellings