If Vancouver’s new city council is serious about supporting measures to help house the middle class, it will not only remove barriers that make approving cohousing difficult and more expensive, but it will also take a more proactive approach in encouraging it.

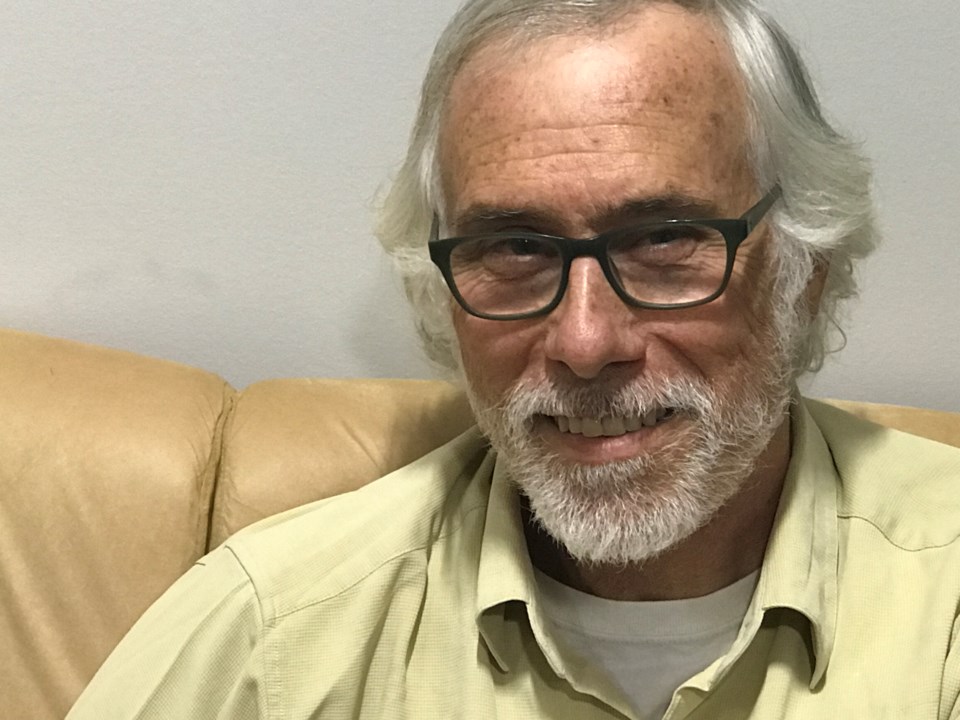

That’s the opinion of Charles Durrett, an American architect who brought the collaborative form of living concept from Europe to North America decades ago and coined it cohousing. He spoke at SFU earlier this month about making cohousing more affordable for families and seniors.

Durrett argues that while city staff and politicians publicly support cohousing, the approval process remains daunting and adds unnecessary costs that residents have to cover.

He maintains the city’s approach to groups that want to build cohousing should be: “How can we make this happen?”

“There’s so much rhetoric around trying to help middle class people stay in Vancouver and such a dearth of reality around that,” Durrett said. “There’s very little traction when it comes to real projects getting to be more affordable… and, over and over again, the cohousing groups would like to make it more affordable.”

While there are a number of cohousing complexes across the Lower Mainland, only one has been completed in Vancouver so far — Vancouver Cohousing on East 33rd near Argyle. Another cohousing building, Little Mountain Cohousing in Riley Park, is expected to open in 2019, while city council approved rezoning for a “cohousing lite” project called Our Urban Village last July. It’s destined for Main Street and Ontario Place.

However, buying into such projects in the Vancouver market can be costly, partially due to land values. Unit prices typically reflect market rates for the neighbourhood, although proponents point to advantages including additional communal space outside individual apartments and a sharing economy within buildings where residents share items such as tools or cars and assist each other with necessities such as child or senior care that make day-to-day life easier and cheaper.

Durrett, who lives in cohousing in Nevada City, Calif., thinks more complexes should be built in Vancouver and that buy-in could be less expensive. He’s concerned potential cohousing groups are being scared off by the often years-long process and money required up-front to see a project get off the ground.

While he said cohousing doesn’t need or deserve affordable housing subsidies, he argues civic governments should actively “facilitate” the unique style of living because it produces “highly functional” neighbourhoods that benefit society as a whole.

The collaborative form of living created through cohousing, he added, also reduces loneliness — a problem that plagues this city based on results from a Vancouver Foundation survey from a few years ago.

“It’s actually hard to support middle class housing because people don’t even know where to start. Cohousing is a great place to start because not only are you boxing people up affordably, you’re giving them a support system in a real high-functioning neighbourhood that they would otherwise have a hard time accomplishing,” Durrett said, while adding that cohousing addresses social issues.

“High-functioning neighbourhoods are hard to come by [that] address pathologies that government can’t really address although they try. They get close and it’s very expensive… There are things that can only be accomplished at the neighbourhood level.”

In terms of some of the unnecessary costs, Durrett points to the fact Vancouver cohousing groups have had to include affordable rental units within their projects as a condition of rezoning.

In Vancouver Cohousing’s case, two of the 31 units had to be rentals in perpetuity. The group had hoped to sell the units to a non-profit organization, but that deal fell through so residents picked up the expense.

In the recently approved “cohousing lite” project, three units will be reserved for affordable homeownership or as moderate income rentals. If the ownership option is selected (it requires a change to provincial regulations), the units would be sold at about 35 per cent less than market value to income-tested buyers.

Durrett considers the expectation that cohousing groups subsidize such units “absurd.”

“Making the middle class subsidize the middle class is not sustainable. In fact, it will scare people away from cohousing. Cities like Vancouver over and over again talk about how much they want to support cohousing and then they do things like that,” he said.

“I mean, would you ever imagine going to a block of 30 houses and saying you 30 houses have to buy and own and manage two houses for people who qualify? You wouldn’t do that. If you wouldn’t do that to them, you shouldn’t do it to a cohousing project. And there are so many line items like that.”

Other ways the city could help reduce cohousing costs are by guaranteeing construction loans and/or guaranteeing residents’ permanent loans, according to Durrett — even if that means rules need to be changed to make that possible.

He estimates that could save cohousing groups hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Costly process

Taryn Griffiths, who attended the lecture, knows how quickly financing and building costs can add up. She’s a member of Vancouver Cohousing, which opened in 2016. It took four years from concept to completion. (Durrett was the initiating architect on the project.)

Griffiths said the Urban Design Panel process “definitely” added to the final budget.

“There was a time delay of a few months plus we had to redesign the project twice because of their rejections,” she told the Courier, although she thinks the community ended up with a better design.

But some changes to the original plans proved pricey.

Griffiths said the 6,500-square-foot common area is almost twice the size the group was initially considering because the city insisted it needed to be larger. The larger size has also created higher ongoing utility and maintenance costs.

The front and sides of the complex, meanwhile, had to be “articulated” to create a more interesting building, which increased the price tag by causing delays in construction.

“There is a lot of work available to construction trades and ours was a difficult build because of articulation and other elements. It was difficult to get trades to complete the work. They would come and do the easy work and then leave for other work. Then we would have to find new trades to complete the work. This created a domino of delays and we ended up behind schedule,” Griffiths said.

The building permit process was also much longer than she imagined it would be — the site was rezoned in April 2013 and the project didn’t break ground until July 2014.

“Our completion date ended up behind schedule by about six months due to the development permit process and construction delays. I can’t put an exact figure on it for additional costs, however it was in the hundreds of thousands of dollars,” she said.

But Griffiths is optimistic Vancouver Cohousing’s experience paved the way for a better process. After they moved in, a few residents were invited to give a presentation to the city’s planning department about cohousing.

“We were able to help them understand how cohousing is different from other forms of housing, the benefits for residents and cities, and we spoke to some of the difficulties we experienced during the process of development,” she said.

“We were the first in Vancouver and it was a steep learning curve for us all — cohousers and the city. I am hopeful for other future cohousing groups that the city wants to improve its process. We get emails all the time from people who want to move into Vancouver Cohousing. So far, only one unit has been put up for resale. It would be great if all Vancouverites had the opportunity to join a cohousing community if they wish to.”

@naoibh