Halfway through the last century, a Vancouver weightlifter with a severe squint, uneven legs and a clubfoot was the strongest man in the world.

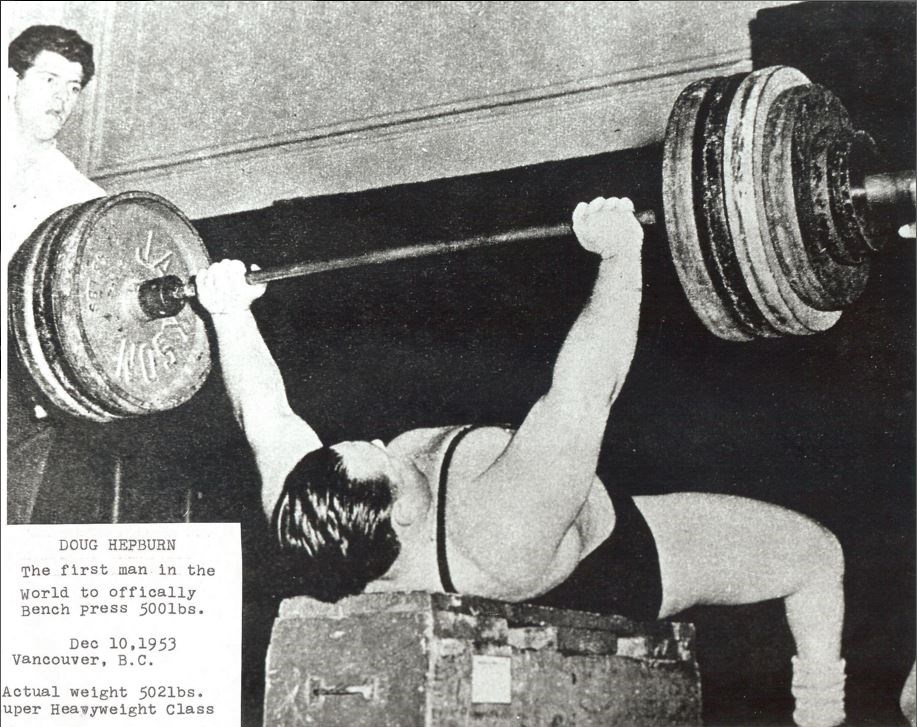

Doug Hepburn was the only known man on earth who could bench press 400 pounds. Increasing his weight by 50 pound-increments over three years, by 1953 he could bench press 500 pounds, a mark that wasn’t broken for six years until an Italian-born WWE wrestler tipped the scales by another 15 pounds.

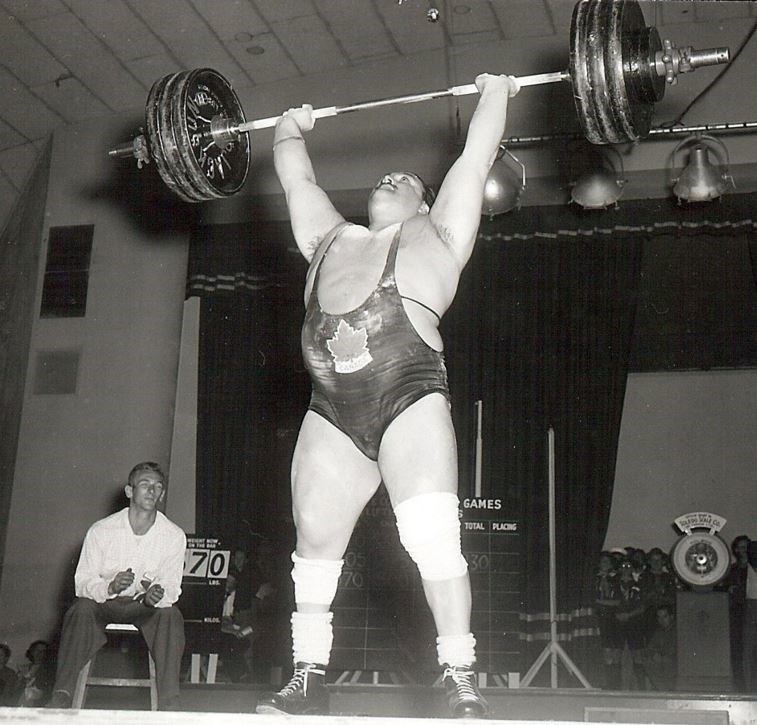

Hepburn was known for his eponymous training strategy of adding incremental weights to daily workouts. Progress from the Hepburn Method was painstakingly slow but undeniably effective. In the heavyweight class (he weighed in at 275 pounds), Hepburn won gold at the 1953 world championships and 1954 Empire Games, the pre-curser to today’s Commonwealth Games. In front of a home crowd at the PNE’s Exhibition Gardens, the 30-year-old strongman gracefully raised 370 pounds overhead in a clean-and-jerk seen in present-day Olympic weightlifting.

Although one of the grandfathers of modern-day powerlifting — in 1990 Ironsport magazine wrote of him, “Remembering […] his lifts were done without steroids or support gear, you'll start to understand why Doug Hepburn stands out as one of history's greatest strongmen” — he isn’t widely remembered today. But the sport he championed is constantly pushing the limits of human capacity while fighting for mainstream recognition, equipment and space.

CrossFit cross over

Hepburn’s sport is experiencing a revival. In B.C., provincial Olympic lifting and powerlifting organizations are growing, and women make up a quarter of the 300-member B.C. Powerlifting Association. Next week at the Commonwealth Championships in Richmond, about 460 athletes will gather for the largest powerlifting competition ever held in Canada.

“We had about 700 members fours year ago and now we’re almost at 2,300,” said Mike Armstrong, the acting president of the Canadian Powerlifting Union, which will host the Commonwealth Championships Dec. 1 to 6.

(Powerlifting is built around three lifts: the bench press, squat and deadlift. Unlike the more dynamic and technical lifts of Olympic weightlifting, powerlifters can move more weight.)

One reason for the popularity surge in both sports is CrossFit, which has its own world competitions and builds workouts around classic lifts such as the snatch and the clean-and-jerk. But not everyone can caster the technicalities.

“I see the videos online and I see the terrible form they use in many examples, but personally I have nothing against the concept. It promotes good general fitness and competition, and there is nothing wrong with that,” said Armstrong. “They find out there is a sport dedicated to that kind of lifting, and they try it out. We’ve picked up a lot of members because of that.”

Tim Frazer reps some shrugs at Taxtix Gym Saturday. Frazer has been an Olympic weightlifter for five years, and his sister and sister-in-law have followed suit. “CrossFit is the culture of the day at the moment. When they want to get good or better, they come to me,” said Mike Cartwright, a 17-time British national gold medallist and two-time world masters champion who has held five world masters records and has lived on the North Shore since 2008.

“The numbers have increased three- and four-fold over the past five years,” said the Capilano Weightlifting Club coach.

Armstrong said powerlifting is also influenced by the raw movement and its back-to-basics principles of lifting without supportive aids or technical clothing such as a “super suit,” a very stiff, elasticized top that helps contract muscles. Men have passed the 1,000-pound bench press benchmark wearing one, compared to the 722-pound “raw” world record.

Dumping the suit has been good for the sport, said Armstrong, who turns 60 next month only recently retired from competition. A world champion bench presser, his personal best is 480 pounds.

“People decided to eschew these super suits and go back to a naturalist T-shirt or loose singlet. That made it a lot cheaper for people to get into and a lot easier for people to learn,” he said, labelling the super suits “legal cheating.” In competition, the methods are typically categorized as equipped or unequipped.

“We’ve more than tipped and it’s only because of this nickname of raw lifting,” he said. “It should be the man and the bar.”

Don’t drop the weights

At Tactix Gym recently, Cartwright rumbled off instructions as novice lifters settled into techniques and others strove to reach new personal bests. “Sit down, sit down,” he purred. “Legs, legs, legs, legs, legs!”

Tactix is one of the few places in Vancouver that allows — and welcomes — the racket associated with weightlifting. Rubberized flooring means bars and plates can safely hit the ground, which they do with a mighty clang.

In contrast, the park board has removed from public fitness centres all specialized Olympic weightlifting flooring as well as bench presses because they are suited for only one exercise. In their place are resistance bands, balance boards, and at the Mount Pleasant community centre, the Synergy 360, which emphasizes body-weight training. After the more niche weightlifting equipment was removed from Creekside community centre, attendance increased.

This is the kind of feedback Jim Bovard would expect. The sport physician, Whitecaps FC team doctor and board member with SportMed B.C. said trends are inevitable but it’s the evolution of sport science that can’t be overlooked.

“If you’re not a professional or Olympian or doing a real power sport, you don’t need to be lifting heavy weights,” said Bovard, adding he was sympathetic to the powerlifters who were chased out of their public gyms when bench presses were removed.

“You are forcing them to change and how are you going to support them? I would say the key point is they should work with those people who feel they are being disenfranchised.”

For their needs and goals, the powerlifters using public gyms had a good thing going, said Bovard. “They have something that works well. How do you argue with success? Just because trends go in a different direction does not mean what they are doing is wrong. But from a collective, public point of view, something may have to give as you’re replacing equipment. Maybe the good news is [the park board] will give them all the equipment so they can keep using it.”

Back at Tactix, a former Canadian junior weightlifter and aspiring senior team member set up a metal rack and loaded a barbell with 350 pounds to zero in on one precise moment of the clean-and-jerk. also Mike Cartwright’s son, Jabob, 20, is five kilograms shy of lifting the national team benchmark, which he must do in competition. On this day, he was focused on building strength in his front squat, just one posture that makes up the explosive lift.

“When you catch the bar in a clean, you have to be strong in the position to catch the moving weight,” he said. “I was trying to get a squat at 350 pounds. I made 345.”

Trying for the heavier weight, he inched the loaded bar off the rack and dropped into a squat. He slowly drove his legs up but couldn’t straighten them completely. His father prompted, “Come on!” But Jacob halted, eyes looking dead ahead as he strained. Before toppling, two spotters reached for either ends of the bar.

The younger Cartwright rolled his eyes as he talked about the predominant aversion to weightlifting at mainstream gyms, both private and public. The restriction he hears all the time is, “Don’t drop the weights.” Chalk keeps sweaty palm dry but is often prohibited because of the dusty, inadvertently territorial prints it leaves behind.

“I go as little as possible, just when everything else is closed,” he said. One of the worst he’s seen in this region put the free weights on a pool deck, making the bars rusty and damp.

“That’s even worse than having no chalk. If you’re lifting a heavy weight and the bar has a tendency to slip out of your hands on the way up, especially if you’re not allowed to drop the weight, you have a higher chance of trying to pull yourself under it as a reaction. I’ve seen people hurt themselves because of the bar slipping,” he said. “It’s a dangerous sport if you don’t do it properly. It’s funny because it’s one of the safest if you do it properly.”

Woman and the bar

Strength is increasingly being studied as an indication of health, intelligence and life expectancy. Last month, Gerontology medical journal published a study that linked sturdy legs to brain power in old age. Numerous studies show how physical activity aids memory, and as the journal Bone reported in October, strong bones are built from weight-bearing exercise and such strength can help prevent osteoporosis in men and women.

Weight training isn’t the only way to build muscle, of course, but lifting increasingly heavy weights until exhaustion is more effective that endlessly pumping a three-pound dumbbell. Walking, jumping and running are other forms of weight-bearing exercise.

Kinesiologist Silvia Hua lifts weights to stay strong at work. In April she expanded her routine at Kensington community centre and joined an Olympic weightlifting class at Tactix Gym, taught by Mike Cartwright. Since then, the 27-year-old has competed twice.

“I was kind of getting bored because it was the same things, and the reason why weightlifting is interesting is there is so much technique,” she said.

At one meet, Hua was the only woman in the 48-kilogram category. At a recent training session, she was one of four women, equal to the number of men.

It’s inspiring to watch other progress because the greatest fight is always against yourself and your own progress, said Hua. “People are very supportive. You’re mostly competing with yourself to hit your personal records but you want the others to succeed as well.”

When she competes, it’s just Hua and the bar.

Twitter and Instagram: @MHStewart